Efforts to enforce a late 2024 divestment policy stalled, leading to a fateful two minutes when a student protest entered a building

In fall of 2024, advocates for Palestine at MassArt were making progress. MassArtists for Palestine, a group of MassArt students and independent artists, had long been calling for divestment from weapons manufacturers, specifically those involved in the Israeli destruction of Gaza. After successfully petitioning for MassArt to cut ties with an Israeli school, and amidst another campaign against a new school protest policy, the group was in talks with the college. On Dec. 7, 2024, MassArt’s foundation board of directors voted to approve a new investment policy that included “a commitment to values-based investing.”

The policy made the school one of five Massachusetts groups to adopt divestment demands since the start of the genocide in Gaza, according to the American Friends Service Committee. It also set off a chain of events that would shock the school.

At first, MAFP didn’t realize the new investment policy was a success. “It didn’t look like it had any enforcement mechanism,” said Gleb Partensky, a now graduated MassArt student and former MAFP organizer. But when Noam Perry, a divestment expert at the AFSC, came to speak at MassArt in March, the tone changed.

To some surprise, Perry congratulated the advocates. “That’s a win,” he recalled saying at a workshop at MassArt’s Student Emergency Response Center, a space in the college dedicated to emotional healing. Students had formed MAFP at SERC meetings in 2023, said Art Mohr, a MassArt senior who helped start the group.

The workshop that day turned into “something of a negotiation space,” Perry said, with Emily Foster Day, vice president of institutional advancement for the MassArt foundation, and Maureen Keefe, MassArt’s then vice president of student development, in attendance. Day and Keefe were as surprised as the students, MAFP members said, that they had heeded activists’ demands for divestment. The administrators did not respond to requests for an interview.

It was a first step that very few schools take, Perry said, and that “the norm is to not have any language at all.” In 2024, MassArt also disclosed its foundation’s investments, which Partensky presented at a March student government meeting, detailing the various ways different equity funds failed to meet the school’s new ethical standard. It is unclear whether MassArt has changed its investment portfolio since.

“What they did was to build the next step for the next wave of activism,” Perry said. “Now the ask is, Implement your policy.”

Motivated into action

“Did we get what we wanted? Yes,” said Isaac Watts, who uses they/them pronouns, “in the sense that it was a clear model on how student demands can be taken seriously, met, and then acted on.” Watts, a member of MAFP, was a 3D arts studio manager at MassArt at the time, and had invited Perry that day after meeting through Watts’ union, the Massachusetts Teachers Association, during a campaign to divest its pension funds, something the union approved in 2024. (Watts was part of the Association for Professional Administrators, which is an affiliate of the Massachusetts Teachers Association.)

Watts’ work at MassArt, a public college, started after Oct. 13, 2023, when their cousin Dylan Collins, a journalist for Agence France-Presse, sustained shrapnel wounds in Lebanon from Israeli bombings that have since been described as a war crime by Amnesty International.

At MassArt, Perry had communicated the divestment policy for both MAFP and school administration. With the new goal of furthering what they now understood as a first step, divestment advocates could organize to enforce the policy. That took the form of an April protest that entered a building for two minutes. The school’s response took activists by surprise, with Watts and another staff member suspended for attending, and police responding to the protest.

“It’s really either you let the students fight the police,” Watts said, “or you try to negotiate and de-escalate and meet the demands. Because really what the policing is doing is delegitimizing the negotiators.”

The day of the protest

The April 24, 2025 protest was organized by Northeastern University’s Huskies for a Free Palestine, Simmons College’s Students for Justice in Palestine, and MassArt’s MassArtists for Palestine.

“[MassArt administration] had stopped communicating with us despite promises to engage about divestment. We were trying to drum the pressure back up,” said Partensky, who declined to comment on if he was in attendance at the protest. The protest started at 3:30 p.m. at Simmons College with a small rally.

Around the corner at MassArt, a student affiliated with the activists propped open an exit-only door to the FabLab, a studio space in MassArt. “I was just letting my friend into the building,” he was quoted as saying in an interview with public safety, described in the police report covering the protest. Watts described the crowd as around 35 people, while the police report and following investigatory meetings estimated 50, many wearing keffiyehs and masks.

Protesters made their way to Evans Way Park, across the street from the FabLab, and in a move Watts, who had no role in organizing the protest, said was unplanned, entered the building.

For just over two minutes, protesters filled a staircase entrance to the FabLab, just barely past the door. The timing was noted in the police report and confirmed by radio transmission recordings obtained from MassArt public safety. The protesters moved inside, insisting their right to be there, according to the responding security officer’s testimony in the report, but the officer stopped them by closing inner fire doors. After a brief commotion in which both the officer and protesters claimed to have been pushed, the protesters complied with orders to leave and dispersed.

The school claimed, in a letter to Watts, that the group of demonstrators chanted “statements to the effect of, ‘We will get you.’” Watts denies ever hearing that, and the officer who recalled the chanting could not remember specifically what words were chanted, as described in the police report. The officer’s recorded radio transmissions also do not corroborate the school’s claim, with no audible protesters. However, in an interview an hour after the protest, described in the police report, the officer says she kept her radio on “so that other Public Safety members would be able to hear the protestors in the background.” In that same interview, she was “unable to determine any identities” of protesters, but one week later, she said she could recognize “Isaiah Watts” [sic], according to the police report.

Watts, who said they personally were in the building for just 45 seconds, said “it didn’t seem to me like the protest had any impact, actually.” Still, the administration maintained that Watts’ conduct was “compromising safety and interfering with the College’s normal operation,” that they “ignored repeated and reasonable orders,” and that Watts caused employees and students “fearing for their safety,” as described in a July 2 letter from the school to Watts. Four days after the demonstration, all students, faculty, and staff received an email labelling the demonstrators’ actions as unlawful.

“The police were immediately called,” Mohr said. “There was absolutely no pretense that any students were going to be protected by the administration.”

Brought up on disciplinary charges

Six MassArt students were brought up on disciplinary charges for the action, though those charges never led anywhere. Mohr, who MassArt alleged was at the protest, was one of those students. “They called me into an office and showed me two pictures and asked me if either of them was me, because they couldn’t tell,” said Mohr, who declined to answer and was let go.

“There was immediate student mobilization,” Mohr said, adding that he and others called in an attorney from the National Lawyers Guild. “Once we showed up with a lawyer, they sort of backed off a little bit,” he said. Partensky added that to his memory, the majority brought up on those disciplinary charges never entered the building.

Years earlier, in a November 2023 protest, campus police held the doors open for protesters to peacefully enter a MassArt building through a public entrance. But in spring 2024, MassArt introduced a new protest policy, which restricted where demonstrators could enter, spurring a strong student response. Soon after, many students showed up en masse to a meeting about the protest policy, which surprised MassArt administration, Mohr said. But the school never changed the policy.

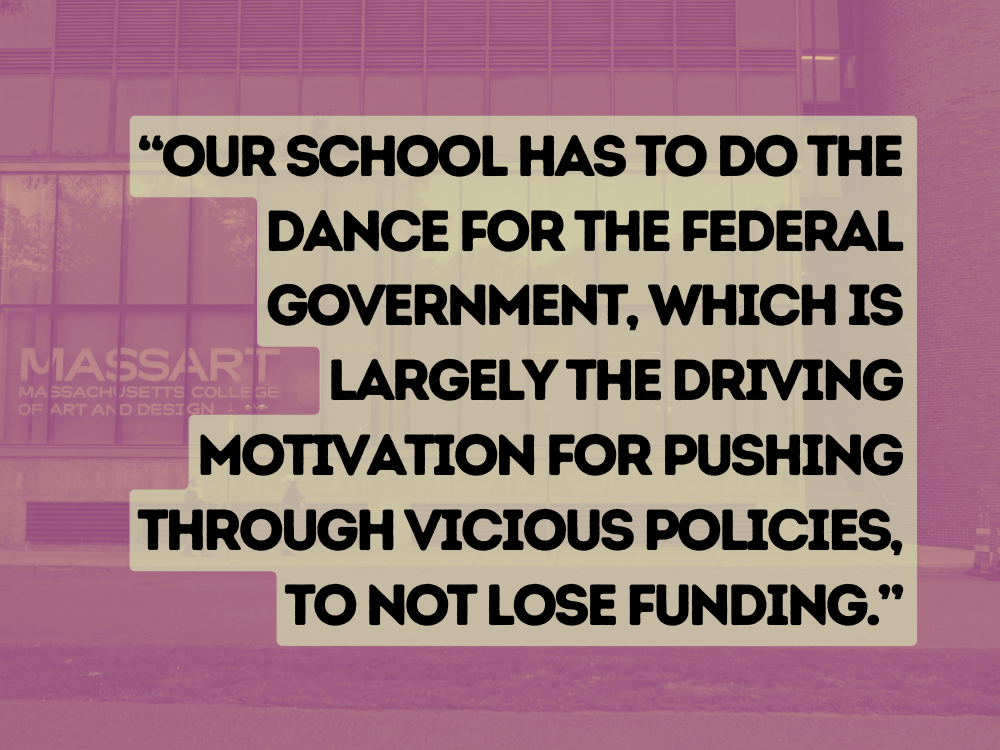

“We’re the only publicly funded art school [in the country],” he said. “Our school has to do the dance for the federal government, which is largely the driving motivation for pushing through vicious policies, to not lose funding.”

Investigated for protesting

On the first Monday of May, Watts went to their last day of work at MassArt. Their boss informed them they had a meeting with human resources in an hour, but wouldn’t say what for, Watts said. The reason became clear when they entered the meeting: in front of them was a small table with a single manilla folder and a box of tissues, they recalled. “And I start laughing and basically run away to go get my union rep,” they said, “because I need somebody else to witness what’s about to happen.”

Watts was being investigated for their role in the protest 11 days prior and was on paid administrative leave until the investigation finished. The notice of their suspension described their actions as unlawful, though the school never sought charges and would remove that claim from later letters to Watts. A line in the original notice told them not to contact others at the college about the matter. Watts and others in the APA said they felt that clause constituted a violation of national labor law in email exchanges with each other, but it was also removed from later statements to Watts, and an unfair labor practice charge was not filed.

Watts’ union representative from the MassArt chapter of the APA asked everyone but Watts to leave the room. “‘Do you see this letter? I feel like this could put me in a camp in ten years,’” Watts recalled telling her.

At this date, Rümeysa Öztürk and Mahmoud Khalil were both still in detention for speaking out about Palestine at Tufts and Columbia University respectively as a result of Trump’s illegal targeting of pro-Palestinian activists. Such advocacy work was, and still is, deeply dangerous. The actions and policies of schools like Columbia were first steps in the escalating repression of activists.

“What happened to the video?”

In early July, following two investigatory meetings, Watts received a return-to-work agreement that included a last-chance letter. The agreement had them promise to not file any grievances or sue and described the school’s version of events. It also included multiple punitive measures, like barring them from entering MassArt facilities through all but two entrances. “I’m willing to accept any and all of these. I would even come back on a last chance letter if [MassArt] corrected the narrative in the letter,” they said. Watts rejected the agreement, and was fired in late July.

They maintain that they never interacted with the public safety officer, were too far from her to hear what the officer told demonstrators in the front, and made no attempt to conceal their identity, which they say is supported by surveillance footage shown to them during their suspension meeting in May.

MassArt public safety refused to supply the footage despite a public records request, saying in an email that sharing it “could result in exposing security vulnerabilities,” like camera placement and interior design of the building. “It’s just my word versus theirs,” Watts said, “but the video shows I’m nowhere close to the thing that they say I did.” Though Watts has not sought to obtain the footage, they wondered what public access to the video would do for their situation. “What happened to the video? It would exonerate me,” they said.

Peggy Wang, a studio monitor for the animation department who was also at the protest with Watts, faced similar proceedings. But Wang returned to MassArt, with extensive surveillance and punitive measures in place, Watts said. She did not respond to a request for an interview.

While Wang had been at MassArt for nearly seven years before the protest, Watts had only been there for two, and under the APA’s collective bargaining agreement at the time, the need for “just cause” in firing started at four or more years of employment. Less than four years of employment, and the employee “may be disciplined or terminated any time and for any reason,” as long as the firing is not arbitrary or capricious and notice is given. This fact was cited in a July 25, 2025 letter that described the president’s decision to terminate Watts, saying their firing was “based on” that lower standard needed to terminate them. The letter also echoed earlier claims that Watts, as one of the protesters, did not initially cooperate with orders to leave, caused a disturbance, and could have threatened safety by blocking an exit.

“In some ways, the school is sleepy and cool and progressive and not as repressive [as other schools],’ Watts said. Although MassArt implemented a punitive protest policy, it had no encampments—unlike nearby Northeastern University—in part because it engaged in dialogue with activists, Watts said. “But that just means that our organizing got further, and then met an edge that was further along than other schools,” they said. “But there still is an edge.”

Mohr attributed the ways MassArt is less repressive to a lack of activist culture at the college, and called the school’s progressive image “completely illusory.”

An unsupportive union

The two investigatory meetings in May, between Watts and MassArt’s chief human resources officer, didn’t go well for Watts, who skipped an early meeting with the school out of frustration, though that meeting was not investigatory. After the meetings, Watts struggled to contact the school directly about the status of the investigation. Despite being told in the May 28 investigatory meeting that they would receive follow up information, they got no responses, as confirmed by emails they shared.

The subsequent union negotiations over a return-to-work agreement were between the APA’s field representative and the general counsel for the council of presidents of the Colleges of the Fenway, a consortium MassArt is a part of. Watts said the negotiation partners worried them. “So the people who are offering me the return-to-work agreement didn’t have any actual sense of what my job was like,” they said.

During this time, Watts and Wang found allies in MassArt students and broader pro-Palestinian groups, which outwardly supported them. A petition sent to MassArt’s president, Mary Grant, received 1,800 signatures and Watts said the MTA’s vice president attended a rally in support of the two. Watts said the union caucus MTA rank and file for Palestine was particularly supportive, a group that they had worked with before on successfully divesting the broader union’s pension from military support for Israel.

The MassArt chapter of the APA, which Watts and Wang both ran for positions in, but lost, was comparatively unsupportive. In an email to Watts, the interim president of the chapter said she would “never forget” Watts’ and Wang’s actions during the protest, agreeing with the college’s claim that protesters scared the responding officer and community at large. “That doesn’t sound like behavior fitting of a MassArt community member,” she said in an email, before adding that she would no longer contact them, but wished them the best.

The response surprised Watts, who remains critical of the lack of support they said they got from the APA. Confusion over representation, disagreements over union policy, and increasingly distraught communications from Watts as they feared for their job underscored the poor communication between the school, union, and suspended staff. APA President Rosa Di Virgilio Taormina declined a request for comment on behalf of those involved at the APA, writing in an email that “the APA cannot comment on individual disciplinary matters or employment status.”

An internal rift over whether to negotiate

The MAFP was also facing its own internal issues. “We ended up having this split,” said Mohr, who mostly stopped participating in the group last spring. The rift was between MAFP members who wanted to emphasize negotiation and those who saw negotiations as futile. Mohr, who identified with the latter, said he mostly stopped working with the group out of frustration.

“Looking back, it would have been a good idea to continue to go to these meetings,” Mohr added, “not in order to try to affect any change, merely in order to listen to what they were saying.” Mohr suggested that by listening and exposing the administration’s point of view through a social media campaign, more pressure could have been applied than by spending time negotiating.

Mohr said he sees student groups as inherently limited in their activism. “Schools are the sites of ideological reproduction,” he said. “As long as you see yourself as a student activist you’ve already lost.” A focus on negotiation, in Mohr’s view, pushed MAFP out of the public eye, as opposed to his emphasis on a continued social media campaign. “You need to continually be engaging,” he said. “And we failed to do that with the students at MassArt.”

Watts, however, saw the value of working with the school. “There has to be some negotiation between the students and the administration about what actual measures are taken,” they said, “for the students to say, We actually divested.”

Recently, MAFP announced that through work with Birzeit University, a school in the occupied West Bank, the group raised $1,250 for a program that helps Gazan students continue their education. While Mohr sees the group as mostly defunct, he said there’s always the opportunity to organize, especially using art as a motivator to political action.

“What I’ve learned,” he said, “is students are really willing to become activated.”