You’re not hallucinating—there is actually agreement and momentum toward psychedelic decriminalization in Mass.

“There was very rarely a day that I would go without being in a tremendous amount of pain,” Jennifer Stell said, describing the cluster headaches that began to strike when she was just eight years old. “It feels like someone has a hot stake and they have drilled it into my head and once it’s in they turn it and pull it in and out.”

At 12, Stell developed chronic migraines, a compounding companion to the headaches; at 14, she turned to cannabis to manage symptoms like nausea and light-sensitivity; and at 17, she was caught with two ounces of the drug. As alternative to a 10-year prison sentence, Stell agreed to attend a treatment program—one that turned out to be “extremely abusive.”

“When I got out, I was very broken and still suffering from these awful cluster headaches,” Stell told me over the phone. “Cluster headaches are dubbed suicide headaches because the pain is so severe some have killed themselves or feel like killing themselves when in a cycle.”

Throughout her twenties—blighted by anxiety, depression, and excruciating pain—Stell sought relief with antiepileptics, antidepressants, heroin, and opiates. Nothing helped. The antiepileptics and antidepressants rendered her unnervingly numb; the heroin and opiates entrapped her in debilitating addictions.

Stell’s prospects seemed intractably grim—until she learned about psilocybin, a naturally occurring psychedelic compound obtained from so-called “magic mushrooms.” Stell tried the drug and at last had a taste of tranquility.

“For about six months straight, I didn’t have a headache or migraine,” she said. “It has completely changed the course of my life.”

Stell is now a nurse in Massachusetts, and a co-founder of Bay Staters for Natural Medicine—a self-described “grassroots team of scientists, clinicians, and patients advocating for commonsense legislation” around entheogens, or psychedelics. Stell and six other activists formed the group in October 2020.

The group’s website touts a trove of research demonstrating the efficacy of psychedelics in treating PTSD, depression, end-of-life anxiety, social anxiety, cluster headaches, alcoholism, and more. It also cites a paper published in the U.S. Journal of Psychopharmacology—and authored by scientists affiliated with towering Massachusetts institutions like McLean Hospital and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center—that associates psychedelics with a reduced risk of opioid abuse. This finding is especially pertinent in Massachusetts, where the nationwide epidemic of opioid abuse is particularly acute.

One of the group’s other six co-founders, James Davis—who connected me with Stell—said in a phone interview that he’s seen dozens of people use psychedelics to “overcome decades of addiction, trauma, and spiritual death” during his time chairing Bay Staters for Natural Medicine.

When I asked about how he got involved in this work, Davis invoked his childhood growing up in a Kansas trailer park. At five years old, a meth lab exploded on his block.“It taught me a lesson that prohibition contributes to the crime and public safety hazards that drug warriors think they’re solving,” he said.

Davis said Bay Staters for Natural Medicine got in contact with members of the Somerville City Council on the very day the group was founded. They secured a meeting just a few weeks later.

Councilor Jesse Clingan—who lost his mother to breast cancer in 2006—told me he was particularly moved by the potential of psychedelics to ease end-of-life anxiety. For that reason, it “wasn’t a tough sell” for him to sponsor a resolution headlined as “supporting the decriminalizing of entheogenic plants”—defined as the “full spectrum of psychedelic plants, fungi, and materials.”

“For me, this is a no brainer,” Clingan said over the phone. “We’re a pretty progressive council, pretty open minded. And especially when things just make sense.”

The resolution—which also deemed the use and possession of all controlled substances the city’s “lowest law enforcement priority”—passed unanimously on Jan. 14.

“I’m hopeful that other cities and towns will move forward with that example,” cosponsor and Councilor JT Scott said. “When we as a Somerville City Council move forward on measures like this—or like the legalization of multi partner domestic partnerships—municipalities across the Commonwealth and across the country take notice and take up their own versions of similar ordinances.”

On Feb. 3, Cambridge’s City Council followed suit. By an 8-1 vote, it approved a resolution requesting that the city manager “direct city staff to work with the City’s state and federal partners in support of decriminalizing all entheogenic plants and plant-based compounds.”

Lead sponsor and Cambridge councilor Jivan Sobrinho-Wheeler said he and his colleagues began working on the resolution several months ago, but were heartened to see Somerville pass similar legislation shortly before they prepared to vote.

“It sort of set a precedent,” Sobhrinho-Wheeler said. “It was great to see the mayor of Somerville and the legal department there be behind it.”

Like the Somerville resolution, the Cambridge policy order also deems the use and possession of all controlled substances the city’s lowest law enforcement priority. Sobrinho-Wheeler started thinking about legislation in this area around January 2020, when he was contacted by activist Frank Gerratana. Geratana is a member of Decriminalize Nature Massachusetts—a grassroots organizing group that formed in late 2019 to advocate for the decriminalization of entheogenic plants.

Gerratana explained that Decriminalize Nature Massachusetts spearheaded talks with Cambridge, while Bay Staters worked more closely with Somerville. Still, Gerratana and Davis emphasized that their two groups closely collaborated to make both resolutions happen.

“I also have to give a lot of credit to the city councilors, because some of them started off not necessarily knowing a whole lot about this issue. But just by looking at the facts and data, and history, they quickly got on board and understood why it’s so important,” Gerratana added. “We’re really thrilled to see so much happening very quickly on the local level.”

This push towards decriminalization in two municipalities may very well indicate a sea change for Mass. Davis said that these resolutions are only the beginning of what Bay Staters for Natural Medicine hopes to see accomplished.

“We are changing attitudes, and we are undermining 60 years of stigma and misinformation that’s permeated throughout our culture about what these plants can do,” Davis said. “When we lean into what the burgeoning science tells us about what these plants can do for depression, anxiety, PTSD—potentially Alzheimer’s and dementia—it’s really hard not to touch people. It’s hard for someone to look in your face and say it shouldn’t be a priority.”

Manifest destiny

Now, Davis said that his team is in talks with city councilors in Boston and Northampton, as well as with a number of state representatives from central Mass. He also said they’re working with state Rep. Mike Connolly on a forthcoming bill, which he says has already garnered around a dozen prospective cosponsors.

I reached out to Connolly, whose district encompasses parts of Cambridge and Somerville. He said during the forthcoming bill is a preliminary step towards realizing organizers’ vision for the state. The measure won’t decriminalize psychedelics, but will rather bring “all relevant stakeholders”—including public health experts—to the table to discuss creating a framework for decriminalization, thereby setting the stage for future action.

Moving forward, Connolly anticipates that psychedelics’ path towards legalization in the state will follow the pattern set by cannabis: first, a vote to decriminalize; then, a ballot initiative on medical legalization; finally, a ballot initiative on full legalization.

“Of course, we tend to be a lot more progressive than many other places in our state. But I think this could happen fairly quickly,” Connolly said, explaining it is “notable” that the Walpole police chief, a well-known prohibitionist, told the Globe that the state’s police groups are unlikely to quarrel with the legalization of therapist-supervised psilocybin therapy—especially for veterans with PTSD.

“You’re hearing right out of the gate—before we’ve even filed the bill—that there are voices even on the side of law enforcement, which historically have been opposed to any sort of liberalization of drug policy,” he said. “I took that as a really solid starting sign that people are willing to be open to this.”

Davis is also optimistic about the pace of change going forward.

“My hope is that we will change the culture and the conversations so much by [2024] or even by next year that we’ll be able to file a bill that is a gold standard for legalizing access to psychedelic plants, and decriminalize—and come up with a new public health-oriented response—to all controlled substances,” he said.

“For many, many different issues, [Massachusetts has] often been a leader,” Connolly said. “Oregon is probably in the lead right now, but we certainly, I think, can be forward looking.”

MGH on MDMA

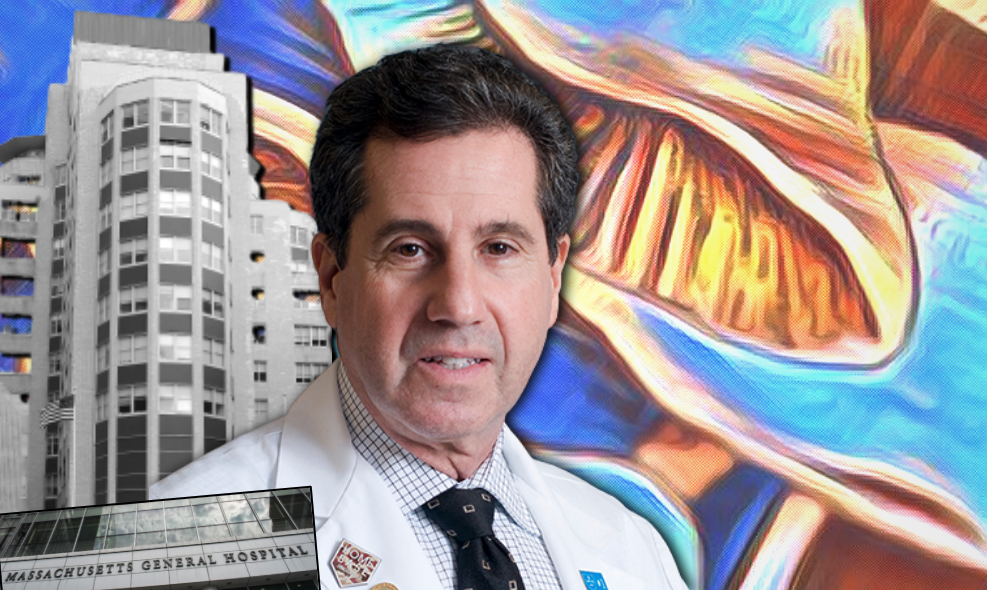

As a hub for biomedical research, Mass is poised to be one of the trailblazers in progressive psychedelic legislation. In another step in that direction, this month, Massachusetts General Hospital officially launches its Center for the Neuroscience of Psychedelics.

Helmed by Jerrold “Jerry” Rosenbaum, a psychiatry professor at Harvard Medical School and the psychiatrist-in-chief emeritus at MGH, the new center will use neuroimaging technology to understand how psychedelics induce structural and functional changes in the brain. The research will specifically focus on psilocybin in patients with treatment resistant depression and MDMA in patients with treatment resistant PTSD.

Researchers at the MGH center will also study the neural effects of psychedelics on the cellular and molecular levels. They’ll do this by taking tissue samples from psychiatric patients and reprogramming the collected skin cells into stem cells. (Stem cells are the “raw material” of the body, and can adapt to perform any function.) The researchers will then coax a patient’s stem cells to transform into neurons and organize themselves into a mini-brain—one that resembles the real-deal organ in experimentally relevant ways. Looking at how various psychedelic agents alter these patient-specific, lab-grown organoids, researchers will glean an understanding of what each of these drugs does to the brain, and how their efficacy might vary across patients with different genetic features and clinical traits.

Since these experiments are conducted ex vivo—or outside of the body—the researchers can safely test out a huge array of psychedelics, including those that are less well understood. In those efforts, the center will probe the therapeutic potential of hundreds of plant samples housed at the Harvard University Herbaria.

“We weren’t interested in doing what everybody around the world can do—and does do—which is take available psychedelics, and study them in this condition and that condition,” Rosenbaum told me on a Zoom call. “I mean, that’s worth doing and important, but we’re uniquely equipped to do things that take it to the next level, like to understand more deeply what’s happening at the cellular and network levels. And to even innovate—to look for novel psychedelics.”

This isn’t the first time the Harvard name has been attached to psychedelic research. Infamous clinical psychologist Timothy Leary spearheaded the Harvard Psilocybin Project in 1960, back when psilocybin and LSD were both legal. But Leary’s reckless, unrigorous, and unethical approach to research scandalized the public and stigmatized the drugs. Charges made against him and his colleague included tripping along with study participants, and also giving the drugs to undergraduates. This misconduct led—some argue—to the criminalization of LSD and psilocybin by all states in 1968.

Rosenbaum’s center is now harnessing the MGH and Harvard names to re-legitimize psychedelic drugs and their clinical potential—an endeavor most welcome to organizers.

“I’m sure the reputational element, the credibility that we bring was seen as helpful to people who are enthusiastic about getting more acceptance in the field,” Rosenbaum said, also acknowledging that a number of “terrific” and reputable institutions like Johns Hopkins and Yale have been conducting research in this area for years.

Rosenbaum described the relationship between organizers and scientists as symbiotic, explaining that decriminalization will make research “a little easier” by mitigating the legal challenges that complicate research on psychedelics and other Schedule I drugs—defined by the US Drug Enforcement Administration as “drugs with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” The de-stigmatization that attends decriminalization, he added, will likely make leadership at hospitals and other research institutions less squeamish about approving projects in the area.

At the same time, while Rosenbaum said he is “all for decriminalization” for psychedelics, he emphasized that he feels “cautious about widespread, unregulated, uninformed use.”

“I do believe in having more information before people get wildly enthusiastic about how safe it is for the brain,” he continued. “There’s still some uncertainty about long term cumulative effects that may or may not be an issue.”

“Defense of our brain”

Anne St. Goar, a physician trained at MGH who co-founded the Boston Psychedelic Research Group, personally supports decriminalization, but advises caution when it comes to non-supervised usage.

“One of the reasons that the research trials are so successful is because they’re given very, very carefully,” she said in an interview.

Recently, St. Goar served as a therapist in a Phase III clinical trial of MDMA-assisted therapy for severe post-traumatic stress disorder. The study was sponsored by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, whose founder lives in Boston and also serves as an advisor to Rosenbaum’s center at MGH. (It’s a small world when it comes to the psychedelic research community.) St. Goar said the results of the MDMA study—soon to make “a big splash” in the New York Times—are “phenomenal” and “irrefutably incredible.” But she stressed that they came out of a rigorous, four-month protocol that MAPS laid out for its participants—each of whom was screened “medically and psychologically.” Subjects also worked with a team of two therapists throughout the course of their treatment, all of which was highly supervised.

Despite her inclination towards caution, St. Goar also recognized that when drugs are embedded in such a rigid protocol, the substances can be robbed of their potential to provide individualized, spiritual healing.

“I think it’s going to be really interesting with time and perspective to see the decrim path and the medical path, and how they will come together and complement each other,” St. Goar added. “Both worlds are going to have to learn from each other.”

Davis recognized the same complex relationship between the concurrent medicalization and decriminalization movements.

“Everyone I’ve met in the medical community here in Boston has been extremely supportive of decriminalization—there’s a lot of synergy,” he added, emphasizing, “Medicalization will really help us create novel applications for chronic illness.”

“[But] a lot of things in life are not a mental illness,” Davis said. “Grief, stress, anxiety—these are side effects of living in the modern world. There’s a blurred line between medical and recreational use for spiritual development.”

Davis said his group supports legalizing people’s access to psychedelics, “whether they have any type of explicit medical need or not.” He also noted that the group supports the right to personal, unsupervised usage.

“We trust adults with good information and harm reduction information to be able to medicate themselves,” he said.

Fellow organizer Michou Olivera—whose psychedelic usage helped her overcome her alcoholism, PTSD from physical abuse, and trauma from growing up “masculine in a female body”—pressed on a similar point.

“I feel that personal usage is the most beneficial and powerful experience that you can actually have,” Olivera said in an interview. “Taking psychedelic mushrooms by myself, in a safe setting in my own space—it has absolutely transformed my ability to deal with my issues on my own.”

Davis imagines a future where there is a network of coops, and perhaps small dispensaries, where people can freely purchase psilocybin mushrooms, as well as a robust, formalized infrastructure of therapists who can provide safe spaces for drug use and offer post-trip integration sessions.

Bertha Madras, a professor of psychobiology at Harvard Medical School and director of the Laboratory of Addiction Neurobiology at McLean Hospital, is hyper-attuned to the potentially blurred line between the medical and personal use of psychedelics.

“What I expect is going to happen without any shadow of a doubt—because we’ve seen it with opioids, we’ve seen it with marijuana—is that [psychedelics] are going to be promoted for wider discretionary use for any reason at all,” she said. “And I expect medicalization to lead to legalization.”

This legalization will lead, she continued, to a “conflation of medical and recreational use without government regulations to protect the public.”

Even when it comes to straightforward medicalization, Madras doesn’t believe the MDMA and psilocybin clinical trials are as promising as advertised. She said the study populations tend to be disportionately white, educated, and already experienced with psychedelics, and often exclude people with psychiatric risk factors. For this reason, “we don’t really know the true risk of the drugs,” she explained, noting that patients prone to psychosis are vulnerable to dangerous outcomes.

“Number one is how solid the science has been published so far,” Madras said. “Number two is the protocols that were used to get the ‘promising data’—can they be scaled [to real-life, clinical practice]?”

Madras gave the second question just as grim an answer as the first.

“What psychiatrist is going to set up a living room for his patients with tenders—with people who are going to sit there for eight hours and hold their hand and talk them through it?” she asked, going on to describe one study that curated hours-long, custom playlists for its participants. “It’s entirely unrealistic to be able to follow a protocol such as this in an average practice where a psychiatrist has 45 minutes.”

She explained that the inevitable divergence from study protocols will have a detrimental impact on the in-practice efficacy of the drugs, since hallucinogens are incredibly sensitive to the user’s mindset and physical environment.

It gets worse, according to Madras: If medicalization does indeed give way to legalization, and unsupervised use proliferates, then people’s trip experiences will become even more dangerously untethered from the study protocols. “Many people will be victimized by it, especially people with underlying conditions or predisposition to psychiatric problems.”

The psychobiology prof also slammed the decriminalization of any type of psychedelics as “completely ill-founded” and “ ill-advised.”

“The number of people who use hallucinogens is fractional, it’s tiny,” Madras said. “By decriminalizing, you literally are going to increase the market … then you’re going to legalize and start a whole new industry based on it with promotions, with advertising. And all of it will be to the detriment of public health.”

“I don’t think of this as a war on drugs,” Madras concluded. “I always say this is the defense of our brain. And it is our brains that are the repository of our humanity.”

Despite voices of concern from medical professionals and laypeople alike, activists like Olivera are still confident that Massachusetts will fully legalize psychedelics within the next few years.

“You can’t silence voices of people’s experiences that are positive and life altering in beautiful ways,” Olivera said with conviction. “The people who are doing this work now are the voices of knowledge and truth that the rest of the world and country and state need to hear.

“It’s a matter of time.”