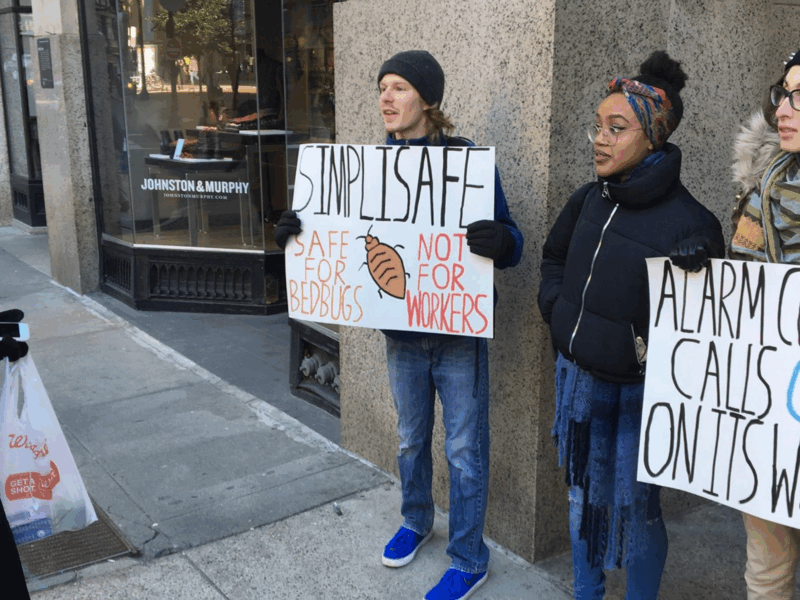

Call center workers battle abusive customers, managers, bedbugs

Abraham Zamcheck had had enough. On Wednesday, Nov 8, the 32-year-old call center representative jumped onto his desk in the offices of downtown Boston security systems firm SimpliSafe and attempted to rally his fellow workers to fight for their rights.

“There are these hurdles the company makes you go through to make you feel like you shouldn’t step out of line,” Zamcheck told the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism (BINJ) in November.

He took action, Zamcheck said, to change that. That action has turned him into a “working class hero,” said Steven Gillis, financial secretary of United Steelworkers Local 8751.

“We call on the labor movement to come to the defense of SimpliSafe workers and all unorganized struggling in this gig, precarious economy,” Gillis said.

Despite the drama of his moment, Zamcheck’s not alone. After months of mistreatment, filth, and apparent abuse, workers at the Boston home security firm are taking matters into their own hands — by petitioning the company to address their grievances and by forming an organization, United SimpliSafe Workers, that they hope will help to unionize their workplace soon.

And they may be part of a new national trend.

“It’s telling that in a moment when traditional unions are under attack, we’re seeing workers come together in new formations, like the workers’ organization that has been formed at SimpliSafe,” said Gillian Mason, the coordinator of development and education at Massachusetts Jobs with Justice.

Mason added that the solidarity movement taking place at the company is indicative of the courage and resourcefulness of labor when confronted with challenges. “It’s a sign that despite an unfavorable political climate, workers are not backing down,” she said. “They’re actually getting bolder and more creative.”

UNITED

“The one main thing in a struggle is to get people to come together,” said Ryan Costello.

Costello, a fellow call center representative, joined with two other members of the company on Nov 6 to protest the latest incident in what employees call a long pattern of abuse at the firm’s downtown Boston headquarters.

This time, it was an infestation in the company’s third- and fourth-floor call centers at 294 Washington St in Downtown Crossing. The bed bugs issue, which has reportedly been a problem since April and continues to plague the company’s Boston offices, was the tipping point for SimpliSafe workers.

“We found out that SimpliSafe had been lying to us and exposing us to dangerous chemicals and pests,” said Costello.

The bed bugs aren’t the whole problem. SimpliSafe workers told BINJ that the company’s treatment of its staff has long been a point of contention — and that, despite the immediacy of the ongoing issues surrounding the insects, all of those issues need to be resolved.

“SimpliSafe does not value the health and safety of its workers,” read a workers’ petition posted in a company break room on Nov 7.

In a statement, SimpliSafe said it was committed to its staff.

“Our workforce is one of our most valuable assets and we are committed to providing a safe, productive and compliant workplace for all of our employees,” SimpliSafe spokeswoman Melina Engel wrote in a statement provided to BINJ.

GOING PUBLIC

Founded in 2006, SimpliSafe has a unique niche in the home security world: a do-it-yourself approach to installing a system to protect your home. The product doesn’t require anyone come into your house to do the work — necessitating the involvement of the company’s call center tech support.

SimpliSafe is, for now, a privately held company. The startup boasts less than 1,000 employees and is in its seventh or eighth year of business. According to a spokesperson for United SimpliSafe Workers, speaking on background, the major question now is whether and/or when to go public.

SimpliSafe’s viability is seemingly a concern for investors, who will only front so much capital. Meanwhile, the company has a product with a narrow profit margin that comes from American workers — both the boxing of security systems for distribution as well as the manning of call centers is done in the US. Manufacturing is tightly subcontracted with China, and the rest of the value of the product comes from its engineering. That’s why a labor dispute like the one brewing in Boston has potential to damage the timing of and revenue from a public offering.

Employees say that their complaints haven’t resulted in much action from the top. Abraham Zamcheck says that’s nothing new. He’s worked for SimpliSafe for nearly a year, though he’s suspended right now for his involvement in protesting the treatment of workers. The problems at the company that the staff are dealing with now, said Zamcheck, are not new.

“The lead-up to this has been since I started working there,” Zamcheck told BINJ. “After seeing how afraid people are, how isolated — there’s a lot of pressure.”

Zamcheck and Costello are joined in their push for more workers’ rights by fellow call center representative Lauren Galloway, 22. Galloway, who lives in Brockton, has worked for SimpliSafe for five months. She joined Costello and Zamchek in their push for workers’ rights, she said, because it was a way to feel less vulnerable. The informal organization, United SimpliSafe Workers, sprung out of that desire to feel protected.

Galloway said her activism came from her circumstances — not a belief system or theory. “This was completely organic for me,” she told BINJ.

A CULTURE OF INTIMIDATION

Staffers at the company go through a rigorous training period that some describe as demoralizing. They call it an “interview,” but it’s a 40-hour regimen. Then there’s a 30-day probationary period, after which staff receive sick days and vacation.

“There are all these hurdles to go through to make you feel like you shouldn’t step out of line,” Zamcheck said.

Costello and Zamcheck work as call center representatives. The task involves tech support and “by and large answering people’s questions about their home security system,” Costello explained. Costello joined the company in late February.

SimpliSafe advertises predominantly on right-wing media, yet its staff is majority people of color and women. Some employees say that combination of factors, alongside the insecurity inherent in the employment, creates a hostile work environment.

Each member of the workforce BINJ spoke to claimed that the company’s management engages in racial and sexual harassment and discrimination. In the most egregious instance, a worker says a white supervisor made a comment to a black subordinate implying that he could rape her because his family had owned slaves in the past.

The staff is allegedly frequently the target of racial and sexual verbal abuse from the people they serve. Complaints about that treatment are frowned upon and workers are not allowed to stand up for themselves under the barrage of hate speech they may be subjected to by customers.

SimpliSafe told BINJ that the company has policies in place to deal with abuse and harassment in the workplace and that the company takes allegations of misconduct seriously.

“When we receive complaints, they are immediately investigated and, without going into details of personnel matters, SimpliSafe takes prompt and appropriate action,” said spokeswoman Engel. “Employees have numerous mechanisms to report issues, including direct supervisors and managerial supervisors on the call center floor, as well as human resources and senior management all of whom are in the same building.”

Engel added that there were also measures in place to deal with harassment from customers.

“As for any alleged issues with customers,” Engel said, “employees are trained to transfer any problematic calls to a manager, for any reason, at their own discretion.”

“There is no democracy in the workplace at present, and because of how poorly we are treated, people are afraid to stand up to SimpliSafe’s draconian policies and practices,” said Costello. “That’s why we are trying to unionize.”

THE PETITION

“We were aware of issues regarding health conditions in the building,” said Zamcheck. “The office is a disease breeding place, there’s no ventilation, it needs to be cleaned.”

Workers knew there was an issue with bedbugs, too. The office had been infested with the insects for months. People complaining of the infestation were sent home and instructed not to talk about bedbugs.

“Through talking to people, we found out there was a major cover-up,” said Costello. “And it’s part of a larger problem at the company of real dishonesty and treating people as if they’re disposable.”

“Chemicals were sprayed,” said Costello, to fix the infestation. But workers say they were told neither of the extent of the spraying nor about the chemical used by the exterminators. The company had staff in the office the next morning. That reportedly led to workers feeling ill. One of Costello’s fellow call center representatives, a pregnant woman, spent the beginning of her shift vomiting from the toxins.

“The fumes were still fresh when we went in the next day,” Galloway said.

That’s normal, says Engel.

“The professional exterminators recommended that there should be four hours between treatment and employees’ return and we followed that guideline,” said the SimpliSafe spokeswoman.

Costello, Zamcheck, and Galloway got together in the wake of the insect infestation and drafted a petition to the company’s management. They were asking, Costello said, for honesty and clarity moving forward so that workers would know the health risks they were taking by working in an environment with both an insect infestation and chemicals.

“We have come to realize,” the petition read, “that we have been deliberately deceived about this infestation; we were told that previous spraying — which occurred over a month ago — was to address the existing rodent infestation.”

“This is a clear violation of Massachusetts state law,” the document continued, “and a deliberate attempt to keep us in the dark so that we will keep working.”

Soon after, people started getting interrogated for their involvement with the petition, a practice known as “captive audience meetings.” Costello sees the interrogations as intimidations in violation of US labor law, designed to produce a chilling effect on the staff. And the threats were real, said Costello, who told BINJ he had seen people fired for standing up against racism and sexual harassment from both supervisors and customers.

“So at 5:15, they came up on me to ask me to come in to be interrogated,” said Costello. “I knew I was about to be fired.”

Costello told Galloway and Zamchek what was happening and the 32-year-old staffer took immediate action. Zamcheck was dragged out by police after being told to leave, but his goal was achieved: Costello wasn’t fired, but instead suspended — with pay.

“I was in jail until 9:30 pm,” said Zamcheck. “Approximately three hours.”

The officers were freaked out about the insects, Zamcheck said. When he went to court the next day, the judge threw out the charges.

“In this period of dead-end, gig, high-tech capitalism, young people like Abraham literally standing up to their blood-sucking call center bosses are the way forward,” said Local 8751’s Gillis.

The petition and the fallout provided a minor but important victory. The entire staff saw the power of their control over their labor as the company’s call center experienced a total work stoppage through the end of the day. The way that workers at the company used their collective power to force a response, said Zamcheck, shows that the “climate of real disposability” in the company isn’t enough to stop the solidarity.

“There was this enthusiasm,” said Zamcheck.

The three have also filed a class action lawsuit alleging wage theft from the company. Attorney Hillary Schwab, who is representing the class, told BINJ that there were a number of circumstances under which staff were not paid for their labor: training and breaks went fully unpaid while required time-and-a-half on Sundays was also not compensated to workers at the company.

“These are hourly, intense schedules, and the workers are not paid for all the work they are entitled to,” said Schwab.

As far as when there will be a solution to the suit, Schwab urged patience. These things take time, she said. “We’re trying to proceed on everyone affected and obtain recovery of the lost wages,” Schwab said.

SimpliSafe did not have much to say about the suit.

“As this matter is in litigation, SimpliSafe will not provide any specific comments on it,” Engel said.

SOLIDARITY AHEAD

“The company is terrified of the power that we have when we come together and stand up,” read a document published by United SimpliSafe Workers after the Costello and Zamcheck incident. “They can pick us off one by one, but when we stand together, as some did yesterday, we have the power to change everything!”

Moving forward, the three activists hope to turn their protest into concrete action.

“Our hope,” said Costello, “is that through this struggle and eventually forcing the company to recognize the existence of the United SimpliSafe Workers, we can have a more democratic workplace where people can discuss and debate issues in the office with their coworkers.”

For now, Costello, Galloway, and Zamcheck are all suspended — with pay. Not being able to enter the office is tough for organizing, though not an insurmountable hurdle.

“This suspension is to silence us,” Zamcheck said.

If so, it’s not working. The three are there in the mornings to protest, then talking to their coworkers at night. The solidarity is real, and the effect of a united front is already forcing change. The company shut down for two days on Nov 22 to spray for bedbugs.

“The thing is, because we have come together and formed United SimpliSafe Workers and begun to organize, the company can no longer sweep this stuff under the rug,” Costello said.

The trio hopes there are more victories ahead. So does Mason, who sees the fight at the Boston company as tied to the broader struggles of labor across the country.

“With even more attacks on unions coming in the next few months,” said Mason, “we are going to need more workers like those at SimpliSafe to come forward without the protection of a traditional union.”

“It’s riskier,” she added, “but necessary in this moment.”

“Workers have every right to protect themselves from indignities and dangers on the job, from sexual harassment to lack of benefits and bathroom breaks to toxic pollution,” Gillis said.

“Despite everything,” Zamcheck said, “people came together.”