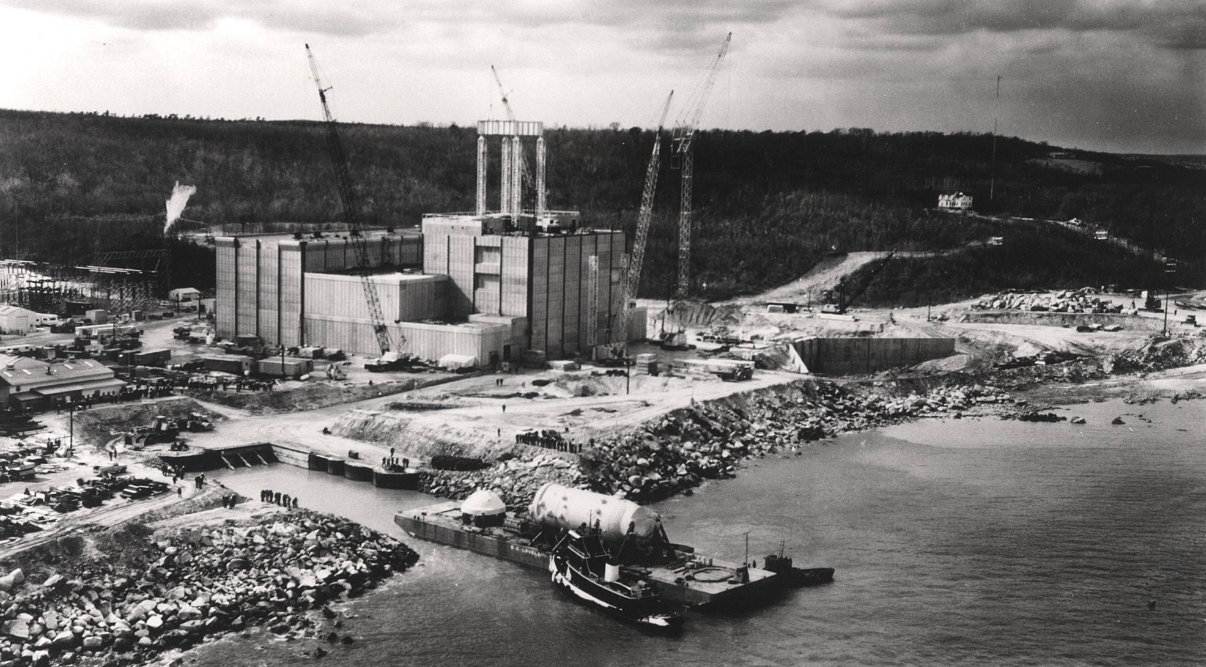

The 525-ton, 65-foot tall reactor vessel for the Boston Edison Company’s Pilgrim Nuclear Station took a month-long, 3,587-mile voyage to go from the fabrication shops at Combustion Engineering on the Tennessee River to the plant site before being nudged into a landing — about a mile south of where the Pilgrims had landed 350 years before

Dear Reader,

The initial project we pursued after launching the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism (BINJ) in 2015 was a feature titled “Dedham and Goliath.” Published in DigBoston and written by Nick Moorhead, the article was the first dive any outlet in our region took into shenanigans and protests around the Algonquin pipeline offshoot being built to carry natural gas through Dedham, Westwood, and West Roxbury. We chose to make our first impression with an article about natural gas for several reasons. Among them: to display our intent to jump on issues that are often tragically ignored and to demonstrate out of the gate that we planned to explore environmental issues that even the alleged liberals at newspapers of record are reluctant to cover.

In the time since, we have reported dozens of features and hundreds of columns, many of which hold accountable the goons who disregard our planet, from local politicians who are more inclined to let condominium developers build towers on the coastline than they are to plan for the impacts of climate change, to international behemoths that pollute with impunity. Even after all that digging, though, the bureaucratic bullies from Nick’s Dedham pipeline story — specifically, from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) — stand out as some of the most ethically scrambled villains of all. By favoring the interests of executives and stockholders over demands of people in communities where pipes were being placed along popular thoroughfares (one stretch runs beside an open pit rock mine that detonates heavy explosives), the regulators proved that there is virtually nothing that can stop Big Energy when there are big bucks to be made. At the same time, the activists who fought them showed that not even a torrent of seemingly insurmountable adversity — from mass arrests, to lawsuits, to officials whose allegiances are to the honchos they’re supposed to keep in check — should get in the way of standing up for public safety.

During my time as a reporter and editor in New England, I have encountered several of the activists who regularly demonstrate against Pilgrim. In 2012, organizers from an Occupy Cape Cod faction brought me to Falmouth to speak about my experience visiting protest encampments across the country, and their volunteers left a lasting impression on me. Unlike the majority of younger occupiers I had met, the mostly senior squadron on the Cape had moved beyond rhetoric and general assemblies, with people spending several hours every week helping their neighbors wrestle with unscrupulous home mortgage lenders. With many of them having bonded through the struggle against the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station over the preceding decades, they understood that it was their responsibility to help out where the government had failed.

When we first asked Miriam Wasser to consider documenting stories about nuclear protests for our BINJ oral history series, several things were different than they are today. For one, it was before an inspector from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) accidentally forwarded a troubling report about the Plymouth plant to longtime crusader Diane Turco, executive director of the anti-Pilgrim group Cape Downwinders; among other damning statements, the email, sent on Dec 6, 2016, noted, “The plant seems overwhelmed by just trying to run the station,” and, “It appears that many staff across the site may not have the standards to know what ‘good’ actually is.” In the time since, as Miriam has spent innumerable hours researching old documents and interviewing people who have been vocally concerned about such risks for generations, its track record of safety problems has continued. During this year’s early January “bomb cyclone” that flooded much of coastal Massachusetts, the plant was forced to shut down after losing one of two external power sources.

Though the NRC appears to be an even bigger joke under President Donald Trump than it was under his negligent predecessors, the intention of this work is not to frighten readers. Rather it is to further alert the public to the bankrupt nature of what passes for real oversight in the United States, even when the lives of millions are potentially in danger. On the strength of Miriam’s hard work and expertise, and of participants who lent their memories and photos to the effort, we hope this time capsule preserves the people’s history and informs this and other movements moving forward. As is explained in detail in this volume, if not for the actions of a dedicated core activist crew on the Cape over a 50-year span, there could be two or three reactors on the bay that may have operated long after the planned closing for next year.

On that note… Pilgrim may be slated to shut down in 2019, but as the struggle chugs along for those who will still live in close proximity to possible contamination from its remnants, there’s no doubt that the forces who have stood up for their health and safety for the past half-century will keep fighting. This is their story.

Chris Faraone, BINJ Editorial Director

INTRO + PART I

Ona sunny morning last September, a small group of men and women met in the Christmas Tree Shops parking lot by the Sagamore Bridge. It was Labor Day, the unofficial end of summer, and the line of cars heading over the bridge out of Cape Cod was steadily growing as the minutes went by.

Two women from Cape Downwinders, the local anti-nuclear group that organized the day’s rally, began to unpack signs and banners from a car. They carried them over to the metal guardrail that separates the parking lot from Route 6. Nearby, Diane Turco, director of Cape Downwinders, struggled with a white pop-up tent. As she fought against the wind to tape the banners to the lightweight metal frame, the two other women, Mary Conathan and Susan Carpenter, put down their banners on the grass and came to help her.

All three wore neon green T-shirts that read “Shut Down Pilgrim” and laughed as they tried to keep the tent from blowing away. After finally getting it strapped to the guardrail with bungee cords, they walked back to the car to get the rest of their signs and greet the latest arrivals.

In all, about a dozen people came to the rally — a smaller crowd than the organizers had hoped for — and they spread out along the road with their banners and signs. Cars began honking almost immediately. Occasionally, someone rolled down a window and cheered.

“I am amazed now how many people are paying attention,” Carpenter said. Up until a few years ago, she explained, a lot of people in the area supported the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station. “People were saying that we need the power and it keeps our rates down. Now people thank us.”

For those on the Cape, the Pilgrim question is hard to ignore — and not only because of regular public demonstrations like the annual Labor Day and Memorial Day rallies at the bridge. Massachusetts’ sole nuclear power plant has been in the news for several problems, including during the most recent winter storms.

In 2015, after a series of unplanned shutdowns, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission downgraded the Plymouth plant’s safety rating and deemed it one of the three worst-performing reactors in the country. Shortly thereafter, Pilgrim’s owner-operator, Louisiana-based Entergy Corporation, announced that it would close the plant by June 2019.

For those at the bridge, the upcoming closure, while exciting, also presents a whole new host of safety concerns.

“What happens at Pilgrim could set precedent for the country, and we’re pushing for Pilgrim to be the poster child for public safety,” Turco said. “Unfortunately, we have a lot more work to do. We hope that we’ve provided a foundation for activism in our community, but this is going to be an ongoing issue.”

With the plant about to enter its final year of operation, and anti-Pilgrim activists planning the next stages of their campaign, it seemed a fitting time to look back at the 50-year fight against one of the country’s most problematic nuclear power plants.

What follows is an oral history of the anti-Pilgrim movement, patched together from extensive interviews conducted with more than 20 experts and activists, many of whom have spent countless hours litigating in court, writing petitions, attending demonstrations, and even sitting in jail cells. The message, tactics, politics, and players have changed over the past half-century, but the underlying effort — to stand up for the health and safety of their families and neighbors — has been unrelenting.

PEACENIKS + PICNICS (1965–1980)

In the mid-1960s, the Massachusetts utility Boston Edison Company began talking about building a nuclear power plant in Plymouth. The company sent representatives to the town to talk with residents and elected officials about the economic benefits such a plant could bring.

MEG SHEEHAN (environmental lawyer, former Plymouth resident): I remember being a kid and growing up in Plymouth. It was a very small town [between 15,000 and 18,000 residents, according to US Census records from the time] and it didn’t have a lot of industry. The local rope factory, Cordage Company … had closed, so the town selectmen were trying to attract new industries.

This was the time period when industry was taking the technology developed during the Manhattan Project and trying to find a commercial use for it. So Boston Edison was trying to convince everyone that nuclear power was clean and safe. I remember that Boston Edison came into town and they had a trailer parked outside of the elementary school. They went around telling people that nuclear power was green and clean and safe; the town selectmen bought it hook, line, and sinker. Meanwhile, we were learning to duck and cover in class.

In 1967, with the town of Plymouth on board, Boston Edison submitted a proposal to the US Atomic Energy Commission — the predecessor of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, or NRC — to build the plant. The agency approved the request, and construction began the following year.

MEG SHEEHAN: That’s when I first got involved. I asked my mother if I could put a sign on our front lawn that said “No Nukes” or “Don’t Build Pilgrim.” I was 13 and my parents lived on Route 3A, so [the construction company] was driving all these trucks to Pilgrim past our house. The sign was very visible.

Lawn signs didn’t stop construction, and Pilgrim began producing power in 1972. Shortly thereafter, Boston Edison announced plans to construct two more reactors — Pilgrim 2 and Pilgrim 3.

BILL ABBOTT (lawyer, co-founder of Plymouth County Nuclear Information Center): [My family] moved to Plymouth in 1973. Pilgrim 1 had just opened a few years before we got here, but we paid little attention to it initially. Then there was a story in the local paper that said Boston Edison was trying to get permits to build two additional reactors, and they were going to do it quickly. They thought the permitting for the next two would be simple. They stated that the second reactor, Pilgrim 2, would open in 1975, and Pilgrim 3 sometime in the late ’70s. The newspaper story concluded, I remember, by saying that there was no known opposition. So they thought these two additional units would be a slam-dunk and they’d have a real fast approval process.

I was living only four or five miles from the site, so I started looking into issues with nuclear power. The more I read, the more concerned I got. … I started reaching out, and I can’t remember how we got hooked up, but I started talking with the Union of Concerned Scientists [and other concerned citizens].

We formed a local group, Plymouth County Nuclear Information Center, called PICNIC, and we became the organization that for the next 10–15 years led the fight against Pilgrim 2 and 3, and then back against Pilgrim 1. … I always thought it was important to have an organization that would be conducting this, and not just an individual.

In 1974 or ’75 we opened a storefront in downtown Plymouth. … It was right by the corner of Main Street and Court Street, on the block next to the fire station. It looked like a political campaign office: It had tables, some posters, and a lot of signage. It basically was a political campaign. It was staffed by one person, and people would walk in off the street and we’d give them literature, just like at a political campaign headquarters. … We’d prepare little pamphlets that we’d print and pass out. It was a black pamphlet and the big headline was “Do you know what plutonium is?” And then a couple lines down it’d say: “You better find out.” Then the inside would be the whole story about how Pilgrim produces plutonium as a byproduct and that it is incredibly deadly.

ED RUSSELL (lawyer, activist, Plymouth resident): I had some knowledge that there was a nuclear plant here, but I wasn’t really aware of the consequences of having that plant until I picked that up from Bill Abbott.

PINE DUBOIS (executive director of Jones River Watershed Association, president and executive director of Jones River Landing): I actually moved to the area [in 1975] because of Pilgrim — well, because of Gerry Studds [who died in 2006], the congressman at the time in Massachusetts in this area. He was one of the shining stars of the anti-nuclear warfare movement and cautioned about nuclear energy, and when I was in Chicago and going to school at the time, he stuck out as somebody that had real things to say and was honest and thoughtful. So I actually moved to the area because of him. … And that’s when Pilgrim 2 was looming on the horizon.

BILL ABBOTT: I am a lawyer, so we decided I would intervene at every single legal point. We filed cases with the NRC, we intervened in licensing proceedings and in environmental proceedings, and we filed suit in Plymouth to try to stop the site from being zoned for two more plants. …

Being in so many simultaneous proceedings at once actually paid off because we could use what Edison said at one proceeding in another proceeding. For example, one of the key arguments they had to make with the NRC [to get the permits for Pilgrim 2 and 3] was that they were in robust financial shape. But at the same time, they were making a case at the state Department of Public Utilities that they needed rate relief. So at the NRC meetings, we would enter testimony from the DPU [hearings]. It really worked.

In 1975, Edison announced they were canceling Pilgrim 3 and that they would just try to get Pilgrim 2 licensed. And they got really close; they were so sure that Pilgrim 2 would be approved that they went ahead and built major components of the plant off-site, spending $300 million. But they couldn’t bring any of these things into Plymouth until they got the permit, which we were fighting [in the courts]. … Then the NRC issued what they called a limited work authorization program, which was something the NRC made up to let some of the building start at Pilgrim. PICNIC challenged that [in court] and it was reversed.

ED RUSSELL: Bill Abbott filed administrative proceedings at every single thing that Boston Edison wanted to do. They had to file a series of applications to do X or to do Y or to report each year on this or that. And he was dogged; he never let any one of them go without appealing. It just wore them down.

PINE DUBOIS: When I came down here, I was working with a non-profit dealing with battered women’s services and engaged in organic agriculture. Boston Edison was transporting pieces of the turbine through Kingston on the road we lived on, and since we didn’t want Pilgrim 2 to be built, we organized the kids that were working with us. I had 23 kids working at the farm, and we started stalking the transport vehicles and [shouting at them], “We can heat with wood, we don’t need nuclear!” We also threw pieces of cordwood at the trucks. [No damage was done, but] the kids had fun and it got into the press. In other words, we tried to challenge them in any way we could to get more awareness about what was happening.

BILL ABBOTT: One of the other things we did during the Pilgrim 2 fight was to hold big public events. We had five or six public debates where I was on the opposition side and there was a spokesman from the plant.

PINE DUBOIS: There was a pretty reliable and active group of local residents that were concerned about Pilgrim and stayed motivated and exchanged ideas and rallied at those events. There wasn’t a single set of people at the time. It was wide ranging, with a lot of people from Plymouth, Kingston, and Duxbury.

BILL ABBOTT: I remember that we had one rally where quite a few people came — about a thousand people. It was right at the junction of the access road to the plant and Route 3A. It was a typical 1960s-style rally with folk music and speakers. I remember Ralph Nader was one of our featured speakers.

BILL ABBOTT: By the end of the ’70s, Boston Edison decided they’d spent enough money and they were going to cancel Pilgrim 2. It was canceled in 1980; we were at it for six years. And after that, we began to focus on Pilgrim 1.

ED RUSSELL: Bill Abbott is a key to what’s happened in Massachusetts. We would have a Pilgrim 2 and maybe even Pilgrim 3 if it weren’t for his dogged litigation back in the day. He was very effective at just keeping Boston Edison at bay, which is why we only have one plant to deal with now.

BILL ABBOTT: We weren’t successful in closing Pilgrim 1, but we got a lot achieved. We got monitors that go on light poles to measure radiation all around the area, and we got the state to institute a real-time radiation-monitoring program.

PINE DUBOIS: After they announced Pilgrim 2 wasn’t going to happen, Reagan was elected and he took the solar panels off the White House and killed every incentive that Carter put in. It was a downhill landslide in terms of environmental protections from there, and we focused on other things — mostly land protection and river protection. We let it go, basically, at least I did. And we focused on things we could do rather than things we could not do.

BILL ABBOTT: This went on for a number of years until other groups sprung up in the late ’80s.

SEA CHANGE (1975–1985)

As PICNIC was fighting Pilgrim in Massachusetts during the mid-1970s, the Public Service Company of New Hampshire proposed a two-unit nuclear power plant in Seabrook, New Hampshire, and another influential grassroots anti-nuclear movement formed in response.

PAUL GUNTER (anti-nuclear activist, co-founder of the Clamshell Alliance): By 1975, a lot of local New Hampshire citizens’ groups like the Granite State Alliance, as well as local newspaper editorial boards and political groups, had started to coalesce around anti-nuclear work and public education. I was brought into the organizing of it that year and got educated on the Seabrook construction issue. At the time, I was involved in prisoners’ rights and prisoners’ family support work in New Hampshire and, interestingly enough, learned about the issue from a group of apple pickers.

The group, the Greenleaf Harvesters, would take a tithe — 20 percent — of their earnings, and at the end of the year would donate the money to some organization. Our prisoner advocacy group had been a recipient of that generosity, and I learned about Seabrook from them.

The next year, the loose coalition of anti-nuclear groups did a march from Manchester to Seabrook in mid-April. We walked onto the then-still-forested construction site and had a rally that [noted Australian anti-nuclear crusader, physician, and Nobel Peace Prize nominee] Dr. Helen Caldicott was featured at. It was the first time I had heard about her, and she spoke so eloquently about the dangers of nuclear power and nuclear weapons.

Anti-nuclear fervor continued to simmer over the spring of 1976, and by summertime, what had previously been an informal coalition of anti-nuclear groups throughout New England coalesced into a group calling itself the Clamshell Alliance. The group pledged to oppose Seabrook’s construction and began an organized campaign of nonviolent direct action.

JOYCE JOHNSON (Falmouth-based anti-nuclear activist): We went up to Seabrook in 1976 and protested there. I remember it was a lot of people and a lot of marching; we just marched and marched and marched through the town. My two young boys were camping with us in the woods too — the only kind of camping my boys had known had been protest camping.

PAUL GUNTER: On Aug. 1, [1976,] during a rally near the construction site, a group of 18 of us walked out onto the site and got arrested. Basically, the police asked us to leave; we said no, so it was criminal trespass. That kicked off and was the opening move of the Clamshell Alliance. A few weeks later, on Aug. 26, 180 of us were arrested.

In the spring of 1977, the Clamshell Alliance planned another anti-nuclear rally outside Seabrook. This time, people from all over New England showed up, and by April 30, at least 2,000 protesters were on site.

PAUL GUNTER: We occupied the construction site, having walked on from neighboring private properties — we called them “friendlies” — that were used as staging areas. Two thousand people moved from these friendlies onto the construction site, and we occupied the parking lot. We essentially set up a community there.

The state of New Hampshire sent officers, and there was a composite of law enforcement from various states — except Massachusetts Governor Dukakis did not and would not send state troopers to that action.

We were subsequently arrested on May Day, and it took them about 16 hours to arrest all 1,414 of us. We were put on National Guard trucks and school buses and sent into five National Guard armories and two county jails. They held us for two weeks because people were in bail solidarity and wouldn’t pay. After two weeks, there were still about 700 people in jail, and finally the state capitulated and released everybody on their personal recognizance.

The ironic part is that essentially the state sponsored, or at least incarcerated, what amounted to a symposium of the anti-nuke movement. People used that time in jail to educate each other on nuclear issues, and we fostered deep bonds that then spread out all over the country. What originally was the Clamshell Alliance turned out to be more of a crab shell alliance since dozens of anti-nuke groups and individuals went back to their respective states and formed a national anti-nuke movement. And to the Clamshell Alliance’s credit, the anti-nuke movement gained public acclaim and credibility.

PINE DUBOIS: We took energy off each other. It was good that the Clamshell Alliance was really active and working hard; so were we. It made a lot of difference to us that there was a sense of a movement rather than the sense of a small group of people going after Boston Edison. I think it made a big difference because the Clamshell Alliance was really strong at the time. I don’t think we were as strong, but we got energy from them.

From there, things began to deteriorate for the Clamshell Alliance because “there were some groups that were no longer satisfied with symbolic actions with guidelines that included no destruction of property,” Gunter says. These philosophical tensions came to a head the following year as the group planned what was gearing up to be its biggest rally to date: another occupation of the plant.

PAUL GUNTER: It was originally planned as a nonviolent action, but Lyndon LaRouche [a controversial political figure known for spreading conspiracy theories] told the governor of New Hampshire that he had an informant who said the Clamshell Alliance intended to destroy property on the construction site. Governor Meldrim Thomson then said he would use everything, including bullets, to stop what he saw as an effort to sabotage the construction of Seabrook. We lost a lot of our friendlies because of that, and soon after, our consensus process broke down.

Some people wanted to hold a rally despite Thomson’s warnings, and so without telling the rest of the group, Gunter says, “a few alliance leaders negotiated a deal with the attorney general of the state of New Hampshire to hold the three-day, on-site occupation legally.” Seabrook’s owners also agreed to the plan, and from June 24 to 26, 1978, thousands of protesters demonstrated while law enforcement stood by.

PAUL GUNTER: We had a huge occupation, but it led to a schism because some people thought it was crazy that we had abandoned civil disobedience by negotiating with the state. There were also some groups that were no longer satisfied with guidelines that included no destruction of property, and these people said, “To hell with symbolic nonviolent actions. We’re going to take to the site.”

From there, there were a couple of actions at Seabrook in 1979 and 1980 that were not supported by the alliance — they attempted to occupy the site by going through fences, by cutting them and pulling them down, but it invited the response of the authorities to prevent the destruction of property.

BILL ABBOTT: Pilgrim 2 was announced before the utility company of New Hampshire announced Seabrook as a plant [in 1972]. Pilgrim 2 should have gone online before Seabrook [did in 1990]. Our opposition mostly took the form of trying to stop them legally. On the other hand, at Seabrook their whole approach was the Clamshell Alliance. They thought lying in the street and getting arrested would stop it. The moral of the story is that you can get a lot of good press that way, but it won’t stop a plant from being built.

PAUL GUNTER: The Clamshell Alliance had some subsequent actions following the 1979 meltdown at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania, but the whole issue of nuclear power was lost in the chaos [of the schism]. It brought on a hiatus in the movement until Chernobyl. Then we got involved again.

BACK IN BUSINESS (1986–1990)

In the early morning hours of April 26, 1986, a failed safety test at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Station in the Soviet Union caused a huge explosion and graphite fire in one of the plant’s reactors. Unlike the United States, the Soviets didn’t house their reactors inside thick containment domes, so an enormous amount of radioactive material escaped from the plant and spread over parts of the Soviet Union and Europe.

The Soviets tried to cover up the accident, but it wasn’t long before the entire world knew what had happened. If the dormant US anti-nuclear movement needed a catalyst to get back out there and fight, this was it. And for many living on the South Shore and Cape Cod, some of whom had never given much thought to the nuclear power plant operating in their backyard, the Chernobyl accident was a wake-up call.

ELAINE DICKINSON (activist with Cape Downwinders): I didn’t pay attention to Pilgrim when it was being built even though I grew up in Weymouth, which is only about 27 miles from the plant. I grew up kind of poor, and just trying to get through college was a hard thing. I was working a part-time job and was just focused on trying to deal with myself. And then Chernobyl happened in ’86. … I remember watching those pictures on the news; Chernobyl made me look at things differently. I remember watching a program where they went back to Chernobyl and showed birth defects and the damage and all of that. And I remember my kids were watching it, and it was horrifying.

PAUL GUNTER: During the construction phase of our protests at Seabrook, we started out with the industry telling us that an accident would never happen. That of course was undercut by Three Mile Island in ’79, but clearly it was indisputable when Chernobyl blew up that nuclear power is inherently dangerous and capable of catastrophic events. The alarm was widespread and reached into the Pilgrim community.

DIANE TURCO (co-founder of Cape Downwinders): My daughter was born in 1981, and that’s when the world became very small. I got involved with the nuclear freeze movement, which was huge back then, and I heard Dr. Helen Caldicott speak with my friend Sarah Thacher — I was 27, I think, at the time. And when I moved down to the Cape, these people that I knew in the freeze movement were also talking about Pilgrim.

PAUL GUNTER: Some of the people that had been involved in the protests against Seabrook took that experience and started engaging in nonviolent direct action at Pilgrim. We participated in meetings and public education events and worked with organizers in and around the Pilgrim community. There was one group called Citizens Urging Responsible Energy (CURE), and sometime in 1986 folks with CURE and the Clamshell Alliance were arrested at the plant’s gate.

LARRY TYE (former Boston Globe reporter): It would have been about 1986, after I covered the Chernobyl nuclear disaster and switched from the medical to environmental beats [that I started writing about Pilgrim]. … I covered everything that went wrong at the plant, from safety issues to controversy over whether it ought to stay open. As I recall, for several years — in addition to my main environmental beat — I was writing a Pilgrim or Seabrook nuclear story nearly every day.

DAVID AGNEW (longtime anti-nuclear activist and co-founder of Cape Downwinders): I moved to the Cape in ’86 — my wife is a native, and her father was quite ill. … Within a month or two, I met some people who were trying to get Pilgrim closed, a group called Mass Safe Energy Alliance: Cape Cod. … I was already against nuclear power, [so] I got involved. …

I remember being impressed with the Clamshell people I met … at Pilgrim when I went to protests. They were people who had come down from New Hampshire. They were very dedicated and seemed to have a lot of integrity. … I’m not saying there weren’t differences [in our tactics], but I was aware of the similarities, not the differences.

LARRY TYE: [When I started covering Pilgrim], people weren’t doing much of the grassroots, in-the-streets anti-nuclear demonstrating at Pilgrim that they were at Seabrook … but there were groups actively opposed to Pilgrim via the courts and ballot kinds of initiatives, and there were lots of angry public officials like Ed Markey and Ted Kennedy and Attorney General Jim Shannon.

DAVID AGNEW: [In the late ’80s], we also worked on getting a citizens’ initiative referendum to close all operating commercial reactors in Massachusetts — it was called “Question 4.” I just remember working to get that ballot initiative on the statewide ballot, and we succeeded. But then we worked to try to get it passed, and we were unsuccessful in that. … It polled very well, but was defeated [in November 1988] after a big, last-minute industry publicity campaign.

LARRY TYE: While Pilgrim never got the national attention that Seabrook did, it actually was a more compelling and troublesome case because it was a much older plant, with fewer of the safety innovations built into Seabrook, and with more questions about how you ever would evacuate people from a place as crowded as Cape Cod and as near to Boston as Plymouth.

MARY LAMPERT (director of Pilgrim Watch): In the late 1980s, even though Chernobyl had recently happened, I was not at all involved in or aware of nuclear power issues. My husband is a lawyer and graduate of MIT, and the feeling in our house was of total faith in technology. We were living in Milton and decided that we wanted a change in scenery and a clean, more rural atmosphere, so we bought a house in Duxbury and moved in ’87. It’s very close to Pilgrim, about six miles away — from my study I can see the plant — but I felt we were moving to a beautiful house in a beautiful town, so what could go wrong?

Pilgrim has been racked with problems since it began operating in the 1970s. Between 1978 and ’79, there were four scrams (emergency shutdowns), one from the blizzard of 1978 and three from lightning strikes. In 1982, the NRC fined Boston Edison $550,000 for mismanagement. In 1983, the plant shut down for a year to fix a mechanical problem. The list goes on.

By 1986, after a critical piping issue forced Boston Edison to shut down the plant indefinitely, the NRC called Pilgrim ‘‘one of the worst-run’’plants in the country. Many in the anti-nuclear movement assumed Pilgrim would never operate again and that they had won their battle, but two years later, Boston Edison announced that after spending $200 million on repairs, it would restart the plant on December 30, 1988.

MARY LAMPERT: Pilgrim had been shut down for about three years and was suddenly in the news a lot. It took me about three days to realize this restart was not a good idea. I thought, “I don’t want to bring my children up in this environment,” so I immediately started taking part in activist meetings and protests.

DIANE TURCO: Governor Dukakis, Senator Ted Kennedy, Senator John Kerry, all the legislators, all the selectmen had said to the NRC, “Don’t restart.” MEMA, the Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency, said, “Don’t restart.” FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, said, “Don’t restart; we’re not ready and we can’t protect the public yet.”

The NRC overruled them all.

SARAH THACHER (longtime anti-nuclear activist, member of Cape Downwinders): They were shut down and we tried to keep them shut down.

DIANE TURCO: So on New Year’s Eve, right around the restart, there was going to be a demonstration at the plant. We had people coming to our house for a party that night, so I wasn’t planning to get arrested. I was just going to be part of the demonstration. But I ended up in jail.

MARY LAMPERT: When I was arrested with the other ladies, we all wore fur coats. We dressed to kill, so we didn’t look like crazy people. … It was actually very funny, one of the best times. We used to have a lot more fun in the ’80s.

DIANE TURCO: We were on the street across from the reactor, and the police said, “Don’t cross that yellow line or you’ll be arrested.” And then one person did. And then another and another. I think 35 people crossed. When [my friend] Sarah Thacher crossed the line, I was like, “I can’t let her go by herself,” and I walked over too. I had no idea where that was going to lead. Sarah Thacher’s what got me into all of this trouble.

SARAH THACHER: We didn’t spend a night in jail or anything; it was just an evening in jail.

MARY LAMPERT: I forget who walked over [the police] line first, but a lot of us walked over. The police escorted us into a bus and an officer said to me and to some others, “Thank you for doing this because we know this place isn’t safe and we could never evacuate the people [if there was an accident].”

We went to the Plymouth jail, and then it became hysterically funny because when we checked in, they wanted your name and address and weight and age. We’re all like, “Are you kidding me? We’re not telling you how much we weigh.”

DIANE TURCO: I remember it was evening and they had the little window with the bars on it too. There were, I think, eight women in a cell, so we were just sitting there on the beds, sitting there talking. And then a man goes, “Is there a Diane Turco in here?” And I yelled, “Yes.”

“There’s a note from your husband.” And I open the note: “I’ll be at the bar down the street. Come meet me there when you’re done.”

I remember they let us out on personal recognizance [and that we wouldn’t take a plea deal]. We went to court because we wanted to acknowledge what we did and that it was important work to try to keep the reactor shut down. I think it took them three days to seat a jury in Hingham District Court, but they finally did.

Turco recalls that one of the first witnesses was one of the arresting officers at the scene that day. During cross-examination, the defense’s lawyer asked him if, as a police officer, he would be required to work and help manage any public chaos should there be an accident at Pilgrim.

DIANE TURCO: He said, “Yes.” Then our lawyer stood up and all he said was “Will you be there?” [The officer] said, “No,” and the judge goes bam with his gavel. Well, that was the end of it. The judge called all the lawyers to the sidebar, and he dismissed the case. I was so mad; I was like “Come on!” We wanted to have a trial and put the whole thing on trial — have Dukakis and Kennedy speak. We wanted to make it a big issue.

To Turco and others, the judge’s action was his way of tacitly acknowledging that he felt the plant is unsafe and shouldn’t reopen. Even so, Pilgrim continued to operate.

MARY LAMPERT: Since the plant went back online, the next thing I did was put a “For Sale” sign on our lawn. There was no way we were going to live here. Our house didn’t sell, even after we dropped the price. I would have conversations with others who were putting their houses on the market, and I can remember this friend calling and saying, “Oh, this really cute couple with two cute children came to look at the house, and I felt morally that I should say, ‘Don’t do this because there’s a reactor right here.’ ”

DIANE TURCO: After Pilgrim was restarted, a lot of people kind of gave up. … The fact that no one other than the NRC has any power to stop Pilgrim from operating was a roadblock for activism. We were floored by the lack of democratic input into the real safety concerns.

BILL ABBOTT: I wasn’t that active when we got into the ’90s [in part because] the NRC made it very difficult for citizens to intervene anymore. It became very hard to stay in a [legal] proceeding, and basically it was my conclusion that it was a complete waste of time. The rules were stacked against you. [Also], different citizens groups like Cape Cod Bay Watch and Cape Downwinders started, and I concluded I didn’t need to be out front.

DAVID AGNEW: Diane and I worked with others in the anti-Pilgrim group Safe Energy Alliance: Cape Cod [in the late 1980s]. And then for some reason or another that faded away, so we formed Citizens at Risk: Cape Cod. At some point that faded away too. I don’t quite remember what happened during the lapse, but I remember that I felt it was important to have an organization …

I had been put in touch with a fellow named John Barrows, and he made an indelible impression upon me. He’s a retired engineer, and he was the closest neighbor living to Pilgrim at the time. He was also a little bit of a weather buff and had a home weather station. He recorded the wind direction near his house for a few years and he plotted that data in a map. It was from him that I learned that some part of Cape Cod is downwind from Pilgrim more than half the time. That’s where I got the idea of calling the group Cape Downwinders.

PART II

SHIFTING GEARS (THE ’90s)

After failing to prevent the restart, the new leaders of the anti-Pilgrim movement changed the focus of their activism. Instead of talking about the dangers of nuclear power in general, the activists “decided to be more focused on Cape Cod.” They decided to pursue two public education campaigns: getting thyroid-protecting potassium iodide pills (KI pills) publicly distributed, and expanding the emergency planning zone (EPZ).

DIANE TURCO: We needed to educate the public on the dangers of Pilgrim by making the risks real on a personal and community level. … People need to be aware that they’re at risk and it’s unacceptable, so we figured if we went with those two points, it would stir up interest in what’s going on …

At the time, people weren’t really thinking about KI. It wasn’t a big public concern, so we had to make that as part of our effort with public education. We worked on legislation to get the KI pills available here for the public in the 1990s and early 2000s.

JOYCE JOHNSON: We did a whole thing about having those pills that we would take if there was a nuclear explosion so we wouldn’t have our thyroids destroyed.

MARGARET STEVENS (activist with Cape Downwinders): We had a campaign to get people to get KI pills, and I remember we had hazmat suits and stood outside town hall with signs saying “Get your KI pills here.” We had musicians out there too.

SUSAN CARPENTER (activist with Cape Downwinders): The KI pill is to prevent one form of cancer — thyroid cancer — but it doesn’t protect against any other form. The rest of the body is completely susceptible to radiation.

MARY CONATHAN (activist with Cape Downwinders): It’s like a pacifier. It’s certainly not a long-term solution.

MARGARET STEVENS: You’d need one of those every day that you’re in the plume.

DIANE TURCO: We say, “It protects the thyroid, not the child.”

MARY CONATHAN: Our lives are in danger, but we have a pill that will protect us for a few hours. We’re just supposed to take our KI pill and go to the basement and wait.

DIANE TURCO: Still, the big thing about us getting it on the Cape is that the state acknowledges we are at risk. That’s the big thing because they kept saying, “Oh no, no, the radiation is going to be dispersed by the time it gets to the Cape. There’s no public health threat.” [If this were the case] we wouldn’t have them. But we do …

What other industry requires medication for the public in case they screw up?

In the second half of the ’90s, as a new generation of anti-Pilgrim activists came together to fight for KI pills and an EPZ expansion, Dr. Richard Clapp, an epidemiologist at Boston University and former director of the Massachusetts Cancer Registry, also started ringing alarms about Pilgrim.

In multiple peer-reviewed studies, he and other scientists documented elevated cancer rates near the facility.

“The closer one lived to Pilgrim, the greater the risk of cancer. The longer and closer a person has lived to Pilgrim, the greater the risk of exposure to harmful radionuclides and the greater the chance of developing radiation-linked illnesses,” Clapp writes.

According to his “Southeastern Massachusetts Health Study,” which was published in the summer of 1996 in the Archives of Environmental Health, “Adults living and working within 10 miles of Pilgrim had a fourfold increased risk of contracting leukemia between the years of 1978 and 1983 when compared with people living more than 20 miles away.”

DIANE TURCO: Dr. Helen Caldicott always goes back to — whenever I say there needs to be a study done about cancer — she says there have already been enough, it’s already documented.

In November 1998, about two years after Clapp published his study, Boston Edison announced it would sell Pilgrim to the Louisiana-based company Entergy Corporation for a mere $80 million.

“We certainly were not happy with that transfer,” Bill Abbott says, “and I remember looking into the finances of it and thinking there was some real concern with Entergy’s financial capability and background. We tried to raise the issues, but the decisions were made.”

According to the activists, not much changed after the transfer — “I don’t think I really thought much about another company coming in because it was still the same reactor and still under the NRC,” Diane Turco says. Though the attacks on September 11, 2001, raised new concerns about the threat of terrorism at nuclear power plants, the activists didn’t really go head-to-head with the new owner until a few years later.

RE-LICENSE TO ILL (THE AUGHTS)

As the federal agency that oversees civilian nuclear power, the NRC is responsible for licensing all plants. A typical operating license is good for 40 years, though plant owners are able to apply for 20-year extensions. Pilgrim was licensed in 1972, meaning that a few years after Entergy bought the plant from Boston Edison, it needed an extension if it wanted to operate past 2012.

In January 2006, the company began the application process.

“Entergy was confident that the facts of science and engineering — in conjunction with following the regulatory process — would determine the outcome of license renewal,” says Patrick O’Brien, senior communications specialist at Entergy Pilgrim Station.

Plants all around the country have successfully applied for extensions. According to an NRC spokesperson, it usually takes about 22 months to complete the process. In the case of Pilgrim, it took six years.

MARY LAMPERT: As a citizen, you can file a request to the board that NRC has, which consists of judges and lawyers, to have a hearing. You can request to take formal part in the process by submitting various legal briefs called “contentions.”

There are only certain issues that are allowed to be litigated, and most you care about the NRC has taken off the table: emergency planning, spent fuel, health impacts. The NRC has decided they’re generic issues, so you can’t litigate them. You can, however, litigate on technical issues.

So you submit a brief to that board explaining what the contention is and what your rationale is. Each contention was 150 pages, and I had five. Then there’s a hearing before the board and questions are asked on both sides. Obviously, Entergy opposed me. The judges made a decision and accepted three of my contentions to move forward, and from there it evolved just like any legal action: hearings, multiple briefs, counter filings by Entergy and NRC. It was a three-ring circus.

I was going to have a lawyer, but she moved to Maui — “I’m sure you’ll find another lawyer,” she said. Wrong. I tried. I put ads in journals and wrote to law firms and law schools from Virginia to Maine — every frigging place I could think of. Every major law firm that does pro bono work had a potential conflict of interest, and little ones wouldn’t take it because they knew it was going to be a long and expensive thing and we probably wouldn’t win.

It was very expensive, but there wasn’t time to go out and have a fundraiser. I was trying to answer responses and move forward in this case. It was a big effort. I budget a certain amount of money that I’ll spend on this issue for the year, and I decided I was not going to spend over $20,000 of my own money. I sent out a letter to my email server list: “Here’s the situation. If anyone can contribute, that’d be great. I need experts on meteorology, pipes, etc.” One person contributed $5. I was almost like “Are you fucking kidding me?” but had to write “Oh, thank you very much, that’s very nice.”

It was very expensive, but there wasn’t time to go out and have a fundraiser. I was trying to answer responses and move forward in this case. It was a big effort. I budget a certain amount of money that I’ll spend on this issue for the year, and I decided I was not going to spend over $20,000 of my own money. I sent out a letter to my email server list: “Here’s the situation. If anyone can contribute, that’d be great. I need experts on meteorology, pipes, etc.” One person contributed $5. I was almost like “Are you fucking kidding me?” but had to write “Oh, thank you very much, that’s very nice.”

So here I am, never having written a brief, while Entergy had their own lawyers and hired a major firm in Washington. The joke is, I’m not a lawyer but was involved in litigation, and my husband is a lawyer but wasn’t involved. One Christmas, I got [former nuclear industry executive turned anti-nuclear activist] Arnie Gundersen as a Christmas present. My husband hired him to help me, and he came to the house with a bow, which was hysterically funny…

I knew with relicensing, there was a possibility that you could wind up not winning the contention, but getting some results. For example, one of my contentions was about leaking buried pipes at Pilgrim, some of which have radioactivity in them. If they’re leaking, then the radioactivity goes into soil and will end up in Cape Cod Bay. So what we argued for was that there needed to be monitoring and soil testing. Before this was filed, there wasn’t one monitoring well, not one on that property. Because of the information I had gathered, it was brought to the attention of Deval Patrick, who put the big squeeze on Entergy. They now have 22 wells. That was an impact.

As Lampert was fighting in court on technical grounds to stop Pilgrim’s relicensing, other groups worked to highlight environmental and health concerns.

PINE DUBOIS: When we at the Jones River Watershed Association realized that they were going for relicensing, we engaged again. We started dealing with the environmental effects of Pilgrim. … We really didn’t want to see the plant relicensed because we thought it was inappropriate and contrary to both public trust and common sense. There was a lot of damage being done to Cape Cod Bay, and the monitoring had fallen off.

MEG SHEEHAN: We were concerned about the impact of the cooling water on the marine ecosystem. We had a lot of documentation about the impacts of that.

PINE DUBOIS: We started to ramp up and started the Cape Cod Bay Watch Program [to monitor and address problems with water quality and marine life in the bay].

MEG SHEEHAN: We also realized that no one had looked at the fact that Pilgrim’s Clean Water Act permit had expired. So we started digging into that regulatory stuff and went to the EPA and got records and monitoring reports. We raised a challenge — we filed a contention — with the NRC saying Pilgrim shouldn’t be relicensing until the Clean Water Act permit was renewed.

PINE DUBOIS: Their permit with the EPA was so grossly out of date.

MEG SHEEHAN: But the NRC punted to the EPA because the Clean Water Act permit was not part of the NRC license [for Pilgrim]. We sent a letter to Entergy and the EPA that we intended to sue because the permit had expired, but based on promises from the EPA that they would [look into it], we didn’t go ahead and sue.

We’ve tried to keep pressure on the EPA, but there’s still no new Clean Water Act permit; they’re operating under a permit that was granted in the 1970s when the plant went online.

DIANE TURCO: Cape Downwinders was also, of course, opposed to relicensing. … [We felt] that they were just going to relicense this reactor, that it was just kind of a rubber stamp. That’s what the NRC is, a rubber stamp machine. …

Part of our efforts was to call attention to two reports commissioned by the attorney general that were very damning about Pilgrim. … Dr. Gordon Thompson and Dr. Jan Beyea did separate studies [about the potential dangers posed by the spent fuel pools at Pilgrim], but they came to the same conclusion that it was an imminent threat to the public because it was densely packed — it wasn’t designed to do that — and that a spontaneous fire could occur.

According to Dr. Beyea’s 2006 report, a spent fuel fire could cause thousands of cancer cases, and the non-cancer-related damages could cost between $105 and $488 billion.

DIANE TURCO: During 2009, ’10, ’11, we were there writing letters to the NRC [and trying to raise awareness about health concerns], but it was not until Fukushima that people really woke up and got involved more.

NO ESCAPE FROM THE CAPE (2011–2012)

On March 11, 2011, a massive earthquake and series of tsunamis wreaked havoc on eastern Japan. The earthquake knocked out power in much of the country, and the subsequent waves flooded about 217 square miles of towns and villages, killing at least 15,894 people — another 2,500 are still considered “missing.” As the government scrambled to respond to the humanitarian catastrophe, another crisis arose: The backup power systems at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant had failed.

With a local news camera fixed on the plant, people watched the accident unfold on television screens across the world. In a matter of days, the plant suffered a series of hydrogen explosions, three reactor cores melted down, and falling water levels in the spent fuel pool sparked fear that radioactive spent fuel rods would catch fire. The Japanese government tried to downplay the severity of the accident, but the meltdown at Fukushima alarmed anti-nuclear activists worldwide. That was certainly the case in Massachusetts — Pilgrim’s GE Mark I boiling-water reactor is the same make and model as the reactors in Fukushima, after all.

DIANE TURCO: After Chernobyl and Three Mile Island, it was only a matter of time [until the next disaster]. That’s what we had been reading, and that’s why we were so concerned with Pilgrim. These aren’t fail-safe. I mean, I actually left teaching early — I retired early — after [Fukushima] happened because this work is so important. … This accident woke up a lot of folks to the dangers Pilgrim imposes to us all.

BILL MAURER (retired engineer and activist with Cape Downwinders): I knew Pilgrim was around, and I mean, I thought about it, but I didn’t think much about it all. Then when I learned about Fukushima, and learned that Pilgrim was the same reactor design, that kind of perked my ears up to see what was happening at Pilgrim. I knew people were concerned about Pilgrim, so I searched out the Cape Downwinders and got sucked in.

SUSAN CARPENTER: I happened to have the TV on when the earthquake hit, and I watched the tsunami live — the live coverage of it was the most horrendous thing I’ve ever seen. Eventually the plant [design] came into question, and I was hooked …

To think that we were dealing with the same thing here, we felt we were in real danger.

MARGARET STEVENS: I was involved with Occupy Falmouth, and when we started focusing in on Fukushima and started talking about it … that’s when I started getting interested in nuclear power. I started researching and talking about it, and the Occupy group talked me into doing a presentation. Maybe 15 people came to that first one, but people continued to be interested, so we formed a little group. There were about nine of us, I think. We called it Pilgrim Anti-Nuclear Action, or PANA. I gave another presentation and we gathered more people into our group, but after a while, after we were doing certain actions around Falmouth, we were saying, you know, we’ve got to get out and go further. We knew about Diane’s group so we started getting in touch … and merged with them.

PAUL RIFKIN (activist with Cape Downwinders): I knew Diane [Turco] from the past from anti-war activism and knew she was involved in anti-Pilgrim stuff for decades. And after Fukushima, she became [even more] energized and focused. … She was sending out emails describing the similarities in the reactors between here and what blew in Japan, and I took it to heart and started going to Cape Downwinders meetings.

BILL MAURER: [At the first Cape Downwinders meeting I attended], my jaw was probably open because the problems at Pilgrim are just so glaring. Part of me said, well, sometimes activists go a little too far and embellish and add some emotion, but the more I looked at it, the more I said, “This is crazy. This is really crazy.”

DIANE TURCO: Fukushima blew away the myth that nuclear power is safe.

PATRICK O’BRIEN: While the design of Pilgrim is similar to that of Fukushima, the equipment, location, emergency response plans, and regulations governing its operations are quite different. Pilgrim is not located in a region susceptible to tsunamis or large earthquakes; it is a single-unit site with a dedicated operations and emergency response organization and has emergency equipment designed to mitigate the effects of flooding. Pilgrim operators have the training, license, and authority to take actions in the event of an actual emergency.

PAUL RIFKIN: [Prior to Fukushima], most people on the Cape — similar to where I was at previously — didn’t know there was a nuclear power plant in our neighborhood. And if they knew about it, they weren’t really concerned about it. So we decided one of the basic things we were going to attempt to do was educate the citizenry so that we could get more numbers on our side and grow as a movement. And then hopefully get the politicians to understand what we’re saying and have an impact on either the governor, whose job it is to take care of the safety of the citizens of the commonwealth, or the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which has the mandate to protect everyone in the country from the dangers of nuclear power plants.

We had facts on our side, we had passion on our side, and we had optimism. So we started doing things, from calling community meetings to marching to going to the nuclear power plant and committing acts of civil disobedience to writing letters to the editor, contacting our congresspeople.

BILL MAURER: Then Diane got a copy of the emergency management plans from MEMA. We went through the emergency plans, and if you read in between the lines, you learned that [in the case of a severe accident at Pilgrim] the Sagamore Bridge was definitely going to be closed, and that the Bourne Bridge might be closed.

With many new and energized members who came to the group in the aftermath of Fukushima, Cape Downwinders started a public campaign highlighting what could happen to their communities if a similar accident occurred at Pilgrim. It was an issue almost guaranteed to rile up the public because, according to the official emergency management plan drafted by MEMA in 1999, the Sagamore and Bourne Bridges — the only roadways into and out of the Cape — were going to be closed to all non-emergency outbound traffic so that people within a 10-mile radius of the plant could evacuate quickly.

PAUL RIFKIN: The state had made a policy that if there was an accident at Pilgrim, one of the first things they were going to do was close both bridges to the Cape. So we wouldn’t be able to get off the Cape! Now why were they doing that? They were doing that, they said, because they wanted the people closer to the plant to be able to escape first, meaning the people in Plymouth and the towns right around Plymouth. And if we were all driving off the Cape at the same time, we would make it more difficult for those people to get out — which is a rational and reasonable thing, except it’s not if you have grandchildren living on the Cape, or if you have property on the Cape, or if you care about not getting cancer and you live on the Cape. Then it becomes somewhat unreasonable.

JOYCE JOHNSON: We’d be trapped here if anything happens.

PAUL RIFKIN: The big thing we started saying then, one of the phrases we came up with, was “no escape from the Cape.”

DIANE TURCO: We’d have dog and pony shows everywhere, and we’d talk about “no escape from the Cape” and why Pilgrim is dangerous.

PAUL RIFKIN: One of the ideas that we came up with was to have a rally at the Sagamore Bridge on Labor Day when people are leaving the Cape.

DIANE TURCO: When the first bridge action was held [in 2011], “no escape from the Cape” was the message. We’d discussed using “Refuse to be a radiation refugee” but agreed that “no escape” was a stronger message for our group. Again, we needed people to identify with the reality that we were expendable collateral damage to the corporate profits of Entergy, and that our government — particularly MEMA — was complicit.

PAUL RIFKIN: The first “no escape from the Cape” rally was very successful. There were 120 people there. There were news teams from Boston, as well as the Cape Cod Times and local coverage, and it made quite a splash. We had a lot of people there with a lot of signs. It was a wonderful celebration of what we were doing.

DIANE TURCO: [After the protest, though], the PR person for MEMA said that the bridges would be open and that our message that the bridges would be closed “couldn’t be further from the truth.”

BILL MAURER: MEMA said it’s not true and you don’t know what you’re talking about. … So we challenged them.

DIANE TURCO: I said, OK, well, maybe I’m misinformed, but I have the 1999 plans, so tell me how I’m misinformed.

I asked for the plans from a local MEMA rep, and he said they couldn’t release them due to “sensitive information,” so then I went to the state police barracks in Bourne. I waited three hours, and [in the end] they just gave me a copy of the 1999 plans — they didn’t have an update.

I called the MEMA office and said I would file a FOIA if necessary [for the updated plans]. I can’t remember if I did file or not, but I did finally get a full copy of the plans.

PAUL RIFKIN: As it turns out, we weren’t full of shit.

DIANE TURCO: Looking through the plans, we found that the bridges are … all blocked off and they’re going to send people into Sandwich. So I’m like, wow, I wonder what the Sandwich people think about this.

I called the emergency director in Sandwich, and I said, “What are you going to do with all of these people in Sandwich?” And he said, “What are you talking about?” And I called the fire chief, the police chief — same thing. None of them knew. Bourne police didn’t know.

BILL MAURER: The emergency management director in the town of Bourne was never told any of this or given a copy of the plan. So we started talking it up with emergency managers on the Cape, and they all said, “No, it can’t be true.”

DIANE TURCO: I called George Baker, who was [then] the head of Barnstable County Regional Emergency Planning Committee. He had no idea about any plans for the Cape.

BILL MAURER: Finally we got Kurt Schwartz from MEMA to come down and explain the plans.

DIANE TURCO: The Barnstable County Regional Emergency Planning Committee held a public meeting with MEMA director Kurt Schwartz … because they wanted to know what the plan was. He said, on Cape Cod, we’re closing the Sagamore Bridge so that people in Plymouth can escape down Route 3, and if people from the Cape try to get off, they’re going to jam up the road. [He also said that] the other bridge will be closed if there is any impediment to traffic, which of course there will be. So both bridges are going to be closed, and he said people on the Cape are going to be told to shelter in place. He actually said they’ll be coming down in hazmat suits and they’re going to determine where the hot spots are, and they’re going to relocate everything living. He actually said that. And just like at Fukushima, you won’t be able to return home for a long time. That is the official state of Massachusetts plan for us.

BILL MAURER: Their jaws dropped; they couldn’t believe it. And when the emergency managers on the Cape expressed some degree of horror, no one had an answer. MEMA didn’t have an answer.

DIANE TURCO: So, bottom line, there are no plans to protect the public, only pieces of paper completed from a checklist of regulations that are meaningless.

BILL MAURER: It legitimized our concerns because prior to that, they were treating us like we were a bunch of tree-hugging hippies overreacting.

ED RUSSELL: As a lawyer, whenever we had a risk in the corporations I worked for, I would look at two things: What is the likelihood that something will go wrong, and if something goes wrong, what’s the dollar exposure, or risk, of an injury or death? If something came in with a low likelihood but a very big loss, I would say you can’t do it. … And with the Pilgrim plant, the liability is enormous. The risk is low, but the result of the potential damage is extremely high. … [The nuclear industry] says, “We’ve thought of everything and we’ve thought of it twice,” but there’s no way you can think of everything. And when you have the risk of destroying Boston, that’s not a risk you can take.

BILL MAURER: I really view it as gambling recklessly with public safety. And whether it’s because they’re making legitimate mistakes or sophomoric mistakes, or they’re doing it on purpose to save money, it bothers me. I’ve given them the benefit of the doubt for so long, but I now really think this has been a bunch of people who have been gambling recklessly with public safety for a number of years.

CHRISTOPHER BESSE (MEMA spokesman): In accordance with federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission guidelines and to keep communities safe, the Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency ensures the preparedness of the state and local communities to effectively respond and mitigate any impacts in the event of an incident at Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plant, including planning, training and exercises involving the communities, Plant and state and federal agencies.

DIANE TURCO: Basically, there’s no plan for the Cape. … It’s all just a cover for Entergy … And it’s corporate profit over public safety, which is, I think, our biggest issue.

In March 2012, about a year after the Fukushima accident, the NRC announced that after reviewing the causes of the accident and the state of the country’s nuclear fleet, all plants must start implementing a new set of safety standards called Diverse and Flexible Coping Strategies, or “FLEX Strategies.” (Colloquially, some people call these new standards the “Fukushima fixes.”)

In mid-May, a few weeks after the FLEX announcement, residents of Plymouth voted 51 percent to 49 percent to tell the NRC to hold off on relicensing Pilgrim until all of the new requirements and upgrades were implemented. But despite this vote and Mary Lampert’s pending legal challenges, the NRC voted 3–1 to grant Entergy’s request for a 20-year extension. (The one no vote came from NRC Chairman Gregory Jaczko, a physicist who often clashed with industry leaders and left the commission shortly thereafter.)

MARY LAMPERT: When I lost the litigation, it was done in the sleaziest of manners. I remember thinking, “What? It’s over? We’re still filing briefs.” The contentions and the hearings had not been completed, but … the NRC declared that Entergy is the winner and the case is over. It was like calling the game in the beginning of the last inning. The chair of the NRC’s commission disagreed, but it’s majority wins.

DIANE SCRENCI (NRC Senior Public Affairs Officer): Although a new late-filed contention had been referred to the Atomic Safety and Licensing Board and an appeal of an ASLB decision was pending before the Commission, the Commission determined it was appropriate to issue the renewed license. The NRC staff had completed its work on the application, issuing both a safety evaluation report and an environmental impact statement, which both found it was safe for Pilgrim to operate for an extended period of time. If the renewed license had subsequently been set aside on appeal, the previous operating license would have been reinstated. For completeness, the Commission declined to revisit the ASLB decision, determining the Board had ruled appropriately. The late-filed contention was not admitted and the hearing was not reopened.

DIANE TURCO: We were all shocked that it was relicensed, but like everything else that people have tried to do though the legal process, this failed. Even Governor Patrick wrote a letter to the NRC saying please hold off on the relicensing because public safety concerns haven’t been addressed, but it was relicensed.

MEG SHEEHAN: We were unfortunately unsuccessful, but we were able to raise a lot of political awareness.

PINE DUBOIS: We took actions where we felt there were substantive reasons for concern and more caution to be exercised by the corporation Entergy. When we were not successful, it was not because we were wrong, but because the nature of the bureaucracy was such that we could not win. But we made a good fight out of it and got a lot of people thinking.

THE PILGRIM 14 (2012–2014)

In the spring of 2012, Cape Downwinders decided to hold a big rally near the plant on Mother’s Day. “We wanted to call attention to the Pilgrim dangers and our demand for closure,” Turco says, adding that they chose the holiday because it’s “a day of acknowledging our responsibility to protect current and future generations and the environment from the dangers of Pilgrim.” So on May 21, 2012 — coincidently just a few days before the NRC extended Pilgrim’s operating license — a large crowd gathered near the plant.

BILL MAURER: The rally was right after I started [getting involved in the anti-Pilgrim movement]. I may not even have gone to a Cape Downwinders meeting yet, but I found out that they were going to have a rally at the plant. So I went up there myself — I didn’t know anybody — and there were only a couple guys; the rest were ladies, older ladies. We looked like the garden club, a bunch of older ladies in sunhats. I mean seriously, there were no young people; it was all older retired people with time.

DIANE TURCO: We thought we would meet at the intersection of 3A and Rocky Hill Road and march toward the plant. They didn’t even let us get near it.

JOYCE JOHNSON: We marched, people made speeches — a lot of people were there. And then we were told not to cross a certain line, of course. But we had made the decision that we were going to.

PAUL RIFKIN: I’ve been arrested three times at Pilgrim [for] performing civil disobedience. Usually it’s the same thing: We go right outside the facility across the street, and we have signs and stuff, and then we cross onto the property. They had barriers, and they knew we’re coming. We tell the police we’re coming, so the Plymouth Police were there and private security for Entergy was there.

DIANE TURCO: We started walking onto the property — Entergy owns that road.

PAUL RIFKIN: We wanted to deliver a letter to the owner saying it was dangerous; we wanted to express our view. We offered it to the security people who worked there, but they wouldn’t take the letter. So we told them, “If you don’t take the letter, we’re crossing the barrier.” And the police said, “If you cross the barrier, we’re going to arrest you.”

BILL MAURER: I remember this older lady was selling T-shirts and said, “You can have it for half price if you get arrested.” I thought she was joking, but sure enough, at the end of the procession and speeches, people started crossing the police line and getting arrested. I’ve never been arrested for things like this, but I said I would do it. So I did it. The joke was that I bought the T-shirt for half price so I had to get arrested.

PAUL RIFKIN: Fourteen of us — including Diane, Bill Maurer, and Joyce — we crossed the barrier and got arrested.

JOYCE JOHNSON: We felt good about it; we were having a good time.

BILL MAURER: After they put us in jail and started processing us, a cop said to me, “You didn’t plan on getting arrested, huh?”

I said, “How did you know?”

He said, “You don’t have enough money to make bail.”

I said, “How much?” and he said, “$40.” I said, “Well, I had $40, but I spent half on a T-shirt.”

He said, “Ask your buddies [for money],” and I said, “I don’t even know these people.” Then he said, “Well, I’ll lend you the money if you need it.”

In the end, Diane and the people running the protest made sure everyone was taken care of, but I thought it was really interesting that the cop was willing to help. The police were always very professional and very nice. … I got arrested one other time, I can’t remember when — probably a little over a year after that — but that was my intro. I got to cross off one of the lines on my bucket list: getting arrested for a good cause.

JOYCE JOHNSON: It was a happy occasion because we were really glad that we were able to do it. Of course, we had to go back and forth to court several times, and that was kind of a nuisance. But we had lawyers that worked for us pro bono, and that was wonderful. To have lawyers who are willing, and believe enough in your cause to represent you for nothing, is pretty nice.

PAUL RIFKIN: [Early on], the DA said, “If you plead out now, we’ll let you off for a fine.” They don’t want to go to trial; it’s a big pain in the ass and they don’t want to give us the PR for it. It’s a game. So we kept going back, and they kept offering us this and that. A couple people ended up pleading out and paying the fine, but the rest of us didn’t want to plead out.

MARGARET STEVENS: We got wonderful notoriety after it.

PAUL RIFKIN: It was great PR. The press loved it, that we might go to jail. People would come to the courthouse with signs: “Support the Pilgrim 14.” Eventually they dismissed the case, though I didn’t want to let it go — “You can dismiss the case, but you can’t dismiss the cause,” I said.

On March 15, 2013, almost a year after the initial arrest, a Plymouth District Court judge dropped the charges. The case was over before it went to trial.

SUSAN CARPENTER: When the judge dismissed it, I was absolutely thrilled that the court didn’t issue us a stay-away order. This meant we were free to continue picketing, rallying, and doing civil disobedience. We kind of wanted a trial, but it worked out well.

PAUL RIFKIN: From the courthouse, when they dismissed us, I put it to the group: “Let’s go back and get arrested again. Let’s go back to Pilgrim and do it again.”

ELAINE DICKINSON: We were all riled up. We had all our signs and noisemakers in the car … and we went to the gates of the plant banging on drums and holding signs.

DIANE TURCO: We marched onto the property with our large banner and signs, and it took some time for Entergy security to notice.

PAUL RIFKIN: We went back and got arrested again.

According to newspaper reports, about 50 people drove directly to the plant from the courthouse and held a spontaneous rally. The police arrested five people, three of whom had just had trespassing charges against them dropped in the Pilgrim 14 case.

The following Mother’s Day, anti-Pilgrim activists once again gathered for a big rally at the plant. Like the year before, law enforcement told the group not to cross the police line onto private property, but 10 people ignored the warning and were arrested and booked on trespassing charges. After being released from jail, the group — which included many of the original Pilgrim 14 — once again refused to make a plea deal with the district attorney.

This time, though, they got what they wanted. The case went to trial.

The defendants called all sorts of public safety and nuclear power experts as part of their strategy to put the question of Pilgrim’s safety on trial.

DIANE TURCO: The courtroom was packed with supporters. We were very honored to represent the citizens’ concerns in a court of law. … We were all in this together and hoped that the state would understand our actions as necessary to protect our communities …

I represented myself, which meant I had an opening statement and closing statement.

From Turco’s closing statement at the trial:

The testimony we heard this week supports the ongoing serious dangers. Fire Chief Kevin Nord of Duxbury testified that in the event of accident, there is “no reasonable assurance” of public safety in his town.

When the question “Would citizens be safer if Pilgrim were closed?” was asked, Chief Nord said, “Yes.”

Dr. Richard Clapp testified from a published study in 1996 that statistically indicated cancer rates are high near Pilgrim and continue to this day. When the question “Would cancers be reduced if Pilgrim closed?” was asked, Dr. Clapp responded, “Yes.”

Dr. Gordon Thompson [said] that consequences from an accident could exceed Fukushima and would include Cape Cod and Boston. He warned of the serious danger of the spent fuel pool holding four times the amount the structure was designed to temporarily hold.

Mary Lampert testified about the futility of working within the system to affect public safety. Testimony from my beloved community of dedicated citizens expressed the real fear, the feeling of entrapment and the need to use every avenue to close Pilgrim in our efforts to protect our loved ones and beautiful Cape Cod.

DIANE TURCO: It was such an interesting trial, and the judge was so nice. She was very interested, and she let us submit testimony and speak. She allowed everyone to make a statement. It was really powerful.

Joyce Johnson, another defendant, also spoke during the trial. In describing her testimony, she refers to one of the newspaper articles she’s saved in a three-ring binder.

“This is me at the trial,” she says, pointing to a photo of her on the stand and beginning to read the article out loud.

JOYCE JOHNSON (reading from the Cape Cod Times article):

One of the more emotional moments in the four-day trial occurred when defendant Joyce Johnson took the stand. … Johnson got out a piece of paper with a quote from anthropologist Margaret Mead. … ‘Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed [Johnson begins crying] it’s the only thing that ever has.’

On March 22, after four days of testimony, Plymouth District Judge Beverly Cannone found the defendants guilty of trespassing. She sentenced them to one day in the Plymouth House of Corrections, though the punishment was symbolic because she counted their time as served.

DIANE TURCO: We got the sense that [the judge] really understood why we stepped over the line, but had to do her job within its confines. … I think she had tears in her eyes when she said we were guilty.

After the trial, Cape Downwinders planned another protest for Mother’s Day 2014.

DIANE TURCO: We met at St. Catherine’s Chapel Park and had a really good march to the plant — we had big puppets and music and everything.

SUSAN CARPENTER: The demonstration was really neat because we had pansies — that’s what a plant is supposed to be, not a nuclear plant.

When we got to the reactor, we had a little vigil there, and [longtime anti-nuclear activist] Sarah Thacher read a statement:

This Mother’s Day action is an expression of our rage against a polluting nuclear reactor and our love for all children. … We are here to put our bodies on the line with an apology that we didn’t understand earlier about this evil that is being perpetrated on our children and generations to come.

After the vigil, as in years past, some of the protesters crossed the police line onto Entergy’s property.

DIANE TURCO: Four of us — Sarah, Susan, Mary and me — walked across the street to start planting pansies, and we were arrested. … We were going to plant flowers and reclaim the land for our children and future generations on the property.

SUSAN CARPENTER: We planned to get arrested. We thought more people would get arrested, but it turned out to only be four of us.

DIANE TURCO: We were in the police transport van when we realized we’re all grandmothers — it was going to be a grandmothers’ trial!

SUSAN CARPENTER: It made the PR better.