About three-quarters of a score ago, before the advent of insanely influential social media and viral justice, I painstakingly identified several hundred items that were pilfered from the Massachusetts State House over the last 200-plus years. I documented the adventure in a cover feature for the Boston Phoenix, but the story wasn’t over. There’s still unfinished business today.

While in one sense it may sound like the fantastical premise of a popcorn caper, in reality it’s a peculiar and painfully slow purloining. The culprit isn’t even really human. It’s a lack of their attention.

Massachusetts has been blessed by countless bequeathments. At the same time, the State House has from day one lagged in the art maintenance department, with the first office to oversee valuable works not opening its doors until 1910. One could steal on Beacon Hill with legendary ease; in 1956, two reporters from the Boston Herald Traveler, in order to highlight security shortcomings, lifted more than $20,000 worth of archived documents without getting caught, and splashed pictures of their gotcha grab across page one.

This wasn’t my first interest in stolen artifacts. Like others who love dirty old Boston, true crime, and fine art, before I went spelunking for disappeared murals of John Adams and of Golden Dome architect Charles Bulfinch, I spent years obsessing over the 1990 theft of beloved works by Flinck and Vermeer from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. My own State House reveal, though, first published in 2012, forever shifted my perspective on lost art and what we should be looking for. The whole of my discoveries, I believed then as I do today, is worthy of at least a fraction of the mass attention paid to the Gardner embarrassment.

What’s missing on Beacon Hill

What happened to the State House is a heist that has unfolded over centuries. As I learned through cross-referencing dusty manifests with works that remain in the collection, the lengthy list of items liberated from the commonwealth includes: assorted ephemera such as Native American arrowheads, more than 400 documents from the Colonial Era, and a 1,900-square-foot stained glass ceiling that was described by the Associated Press as “one of the largest single skylights in the country” before it was removed from the House chamber in 1970 and presumably parsed among reps who hoarded the pieces as mementos.

The list goes on; in 1984, page one of the 1629 Massachusetts Bay Company Charter was even stolen from the State House basement along with the wax seal that King Charles I stamped on the document. Though investigators never found out who specifically nabbed the charter, the list of likely doers included some of the same suspected characters linked to the Gardner ordeal six years later. The 17th-century document showed up during a drug raid in Dorchester within months, while the seal was found more than a decade later in an unrelated Randolph sting.

Amateur larceny probably accounts for most of what has vanished from the State House, keepsakes nonchalantly pocketed by lawmakers and legislative aides with sticky fingers. A select few robberies, however, resemble more the work of professional crooks, the likes of whom may have also swiped a sculpture of early public education advocate Charles Brooks.

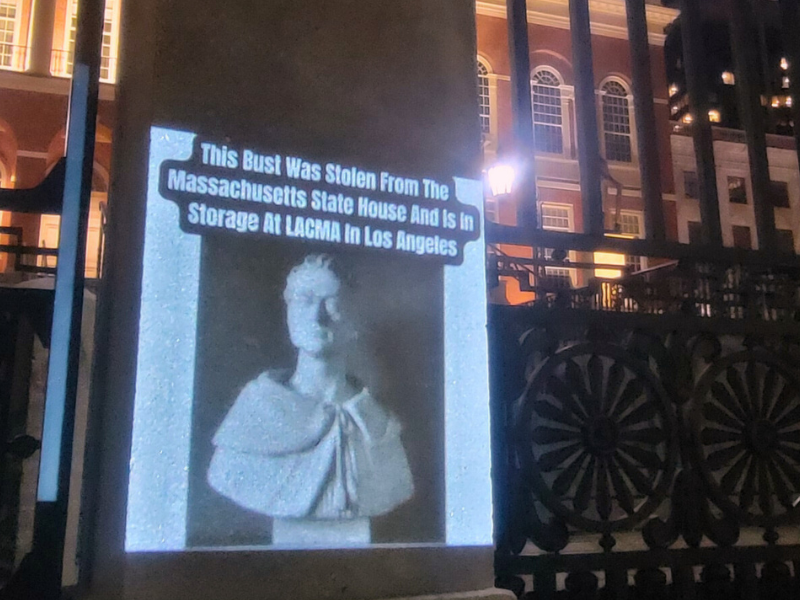

It’s not as thrilling a tale as the Gardner gank, but there is one major difference that the public ought to find compelling—unlike the vanished Vermeer, this bust has been located. I traced the sculpture of Brooks, a mentor of Horace Mann who helped establish normal schools in America, from Beacon Hill to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), where it’s currently in storage.

Origin of the sculpture

The journey of the bust begins in 1835, when prodigious artist Thomas Crawford moved from New York City to Rome, where he was among the first American sculptors of significant renown. According to documents I found in the Houghton Library for rare books and manuscripts at Harvard University, Crawford was commissioned for the bust in the early 1840s, around the time he started work on “Orpheus and Cerberus,” a marble version of which is housed at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (he is perhaps most famous for sculpting the “Statue of Freedom” atop the US Capitol). From my earlier reporting:

- Crawford’s career was helped greatly by Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner and George Washington Greene, who was the American consul in Rome at the time. It was presumably through them that Crawford met Brooks, who apparently first requested a bust of himself in 1842. Crawford quoted Brooks $250—his “established price”—and it appears that he was paid $100 up front with the remainder coming years later.

- Crawford wrote his subject several letters in the 1840s. Though the bust has in the past been catalogued under the date 1842, correspondence shows that while Brooks and Crawford started negotiating the cost in that year, the artist continued working on the sculpture into 1843. “I am at present completing your bust—and hope to have it ready for a ship that is expected at [the Italian port city] Leghorn arriving next month,” Crawford wrote on May 19, 1843.

- The amount due after the deposit, according to the correspondence, was $178—most likely $150 for the marble bust, and an additional $28 for a form cast that could be used to make duplicates. According to a July 18, 1843, letter from Crawford, Brooks had also requested four plaster facsimiles to be molded and shipped with the original marble sculpture. In that same note, Crawford apologized for his tardiness:

“An unexpected delay has occurred, in consequence of the caster not having been able to [indecipherable] when he had promised for the purpose of making the mold. I did hope and so expressed myself an answer to your letter from Paris that the bust might leave Rome with the statue of Orpheus and other works which were ready at the time . . . It was only a week since that the caster could apply himself to make the mold and he is now casting the four copies you desire. They will require several days to dry well before it will be possible to pack them and then all will be ready for the departure.”

There does exist an 1845 receipt sent by Crawford to Brooks for a total that would have included the copies, but I was unable to find evidence that any of the duplicates ever arrived in America. The Brooks bust in storage at the LACMA is marble, so what’s important is which piece was at the State House—the original that’s in Los Angeles, or a knockoff made of plaster. Leads are inconclusive. A 1907 biography of Brooks vaguely notes that a bust given by his estate was “placed appropriately in the office of the State Board of Education, Massachusetts State House.” Similarly, a 1924 State House Guide Book merely acknowledges that the gift was received by the commonwealth in 1892, “conforming to the wishes of his family.”

How the Brooks bust landed in Los Angeles

As my research also showed, besides there being no trace of plaster Brooks busts anywhere, the best proof that the sculpture in Los Angeles came from the State House seems to be an auction record dating back to 1992. Though the identities of the seller and buyer are private, a marble bust of Brooks—perfectly resembling the item in question—was auctioned off by the Hub-based Grogan & Company for $6,000 on December 9, 1992.

The following year, a marble bust of Brooks was donated to LACMA by a Mr. and Mrs. Herbert M. Gelfand. I compared an image of the work from LACMA’s catalogue to a photo from the 1920s that was snapped at the State House, and they appear to be identical—both with distinct marble characteristics right down to a signature spot on the base beside the subject’s birth year.

In 2012, a spokesperson for the commonwealth said the bust missing from Boston is not the sculpture I found in Los Angeles. They had no way of knowing though and declined to peruse my files. Later, a source close to former Gov. Deval Patrick told me the administration felt my article drew unnecessary negative attention, and internally committed to not helping.

Meanwhile, the media contact at LACMA promised to examine relevant documentation, but then stopped returning my phone calls and emails. The museum also commented on its website: “LACMA is looking into it and has in fact been in touch with the state of Massachusetts about the work. Pending the outcome of those discussions, LACMA is prepared to work with the state of Massachusetts to take appropriate action.” But nothing ever came of it.

I quit pestering them about ten years ago after another LACMA donor told me off the record that the institution would never risk embarrassing a benefactor by conceding that the piece was stolen (even though the donor couldn’t possibly have known about the questionable provenance, but rather likely had a buyer on the hunt for historical pieces from that era). Times and the people in charge can change though, and so when the same source recently pinged me to say that Gelfand passed earlier this year, I decided that it is finally time to make my move.

Next steps to retrieve the bust

Along with this column, I am going to post several videos about the Brooks sculpture. They will range from background on the bust, to a look at other stolen goods which have wound up in the Los Angeles museum (enough that the Hollywood Reporter published an article last year asking, “Does LACMA Have a Looted Art Problem?”).

On the Massachusetts side, I cannot stress enough that I am not attempting to open old wounds or to shame anyone. The small office that handles state art has been historically starved, and has made substantial progress in restoring tattered old works despite the lack of preservation funding. With that said, I am writing to Gov. Maura Healey and some other leaders who can act now to help retrieve the bust from LACMA; in doing so, they can prevent any further embarrassment and, better yet, emerge as the protagonists after a string of governors who looked the other way.

As for LACMA, it’s not too late for curators to proactively return the sculpture either. Pressure from a single journalist wasn’t enough to compel stakeholders on either side to budge last time, but things could go differently this round, and it would be a shame to get dragged through the mud and flamed online just so your institution can hoard a bust that’s been collecting dust in storage anyway.