BOSTON – Diane Barylick, 71, is currently planning her own funeral—a fact that she shared with the 14 people gathered for a Death Cafe at Fenway Community Center on Sept. 28. Barylick wants to have her funeral at her home, be wrapped in dark green velvet (for her birthstone), and be buried in a biodegradable casket.

Barylick, who works as a hospice caretaker, found out about the Fenway Death Cafe through an advertisement. The event is part of a larger movement that features pop-up group discussions about death in an effort to break the taboo around the subject. According to the Death Cafe website, the objective is “to increase awareness of death with a view to helping people make the most of their (finite) lives.”

The idea for Death Cafes originated from Swiss sociologist Bernard Crettaz in 2004, and was organized into a group movement by Jon Underwood in the United Kingdom in 2011.

By 2012, the movement spread to the United States, and continued through the pandemic with virtual meetings. Underwood’s mother, Susan Barsky Reid, and sister, Jools Barsky, have been running the Death Cafe website since his sudden death in 2017. According to the Death Cafe website, they have held 22,164 Death Cafes. The events themselves are led by volunteers, like organizer Carol Lasky.

When Lasky walked into the Fenway Community Center nine years ago, she knew it was the perfect location to host a Death Cafe, adding it to the list of many locations worldwide that support the movement. Other volunteers have led Death Cafes in Somerville, Brookline, and Salem.

The Fenway Community Center is surrounded by floor-to-ceiling glass windows that allow passersby to look in and occupants to look out. This transparency, according to Lasky, is perfect for the event.

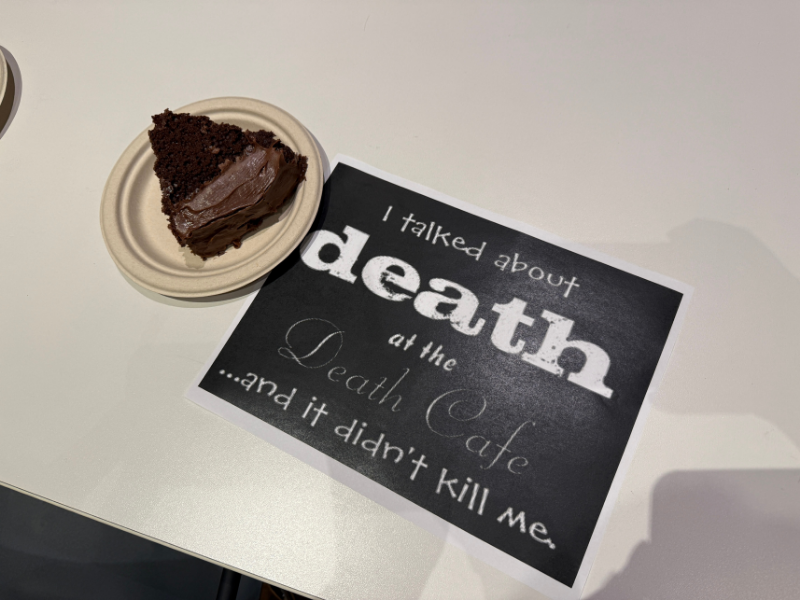

“You all aren’t here for the Death Cafe, just chocolate cake,” Lasky joked as she passed paper plates and cake around the table at the beginning of the discussion. Chocolate cake and tea are fundamental parts of a Death Cafe, according to Lasky, as a nod to Death Cafes’ British origin and a taste of comfort during a difficult conversation.

The following two hour discussion was driven by the questions, experiences, and fears the participants brought to the table—Lasky isn’t allowed to use a prepared agenda. Most of them had never attended a Death Cafe before.

“It all depends on who walks in the room,” Lasky said. “We had some extraordinary people around that table who had such great things to offer. There’s the magic.”

Through the Fenway Death Cafe conversation Barylick realized that witnessing death in her work as a hospice caretaker has affected the way she perceives her own death.

“I want the kind of death I’ve provided numerous clients,” Barylick said. “Don’t force feed me water. I want to be comforted. My favorite music is playing. Keep my lips moist with Vaseline.”

In contrast with a younger woman a few seats over, who admitted that she avoids thinking about her own death, hospice caretaker Barylick expressed acceptance for the reality of dying.

“My endpoint is coming,” Barylick said. “I’m in the fall of my life, heading towards winter.”

Her funeral plan is an effort to make the process easier for her executrix, a good friend. Instead of leaving her grieving friend to decide how to properly honor her once she dies, Barylick is taking a proactive approach to death that falls in line with the message behind Death Cafes.

The ages of participants ranged from early 20s to 70s. According to Lasky, this generational diversity is common at this location because it is close to universities.

To Husnain Shah, 25, Death Cafes are important because they provide a space for people to casually discuss death without it seeming strange.

“Not that I’m like, ‘Dude, I love death, I need to talk about it all the time,’” Shah said. “It’s just refreshing to have a space to talk about it.”

Shah is a graduate student and full-time fellow at Simmons University. He is in charge of organizing events at the Simmons library, where he is now planning to host a Death Cafe. He checks the Death Cafe website almost every day to see when the next Fenway Community Center one will be, with hopes of seeing some familiar faces and learning more from people with different perspectives from his own.

“[Lasky], who was mediating, gave a lot of control to us who were participating in the Death Cafe,” Shah said. “I think that works in its favor, at least for that group we all were in were talkative and had a lot to share, so it worked really well.”

The topic of death is more common among older generations because of the likelihood that they have experienced someone close to them dying, according to Shah.

“Whereas for younger people it—not to say we’re babied by lack of death, but that’s just how life happens—when you’re 20 you’re not really thinking about it,” Shah said.

But for people like Shah, who have experienced the death of a loved one, there are fewer opportunities to talk about these losses with people of any generation. He said that the taboo around talking about death is decreasing, but people were still surprised when he said he was going to a Death Cafe; the topic is not completely normalized just yet.

“It’s just like the saying, ‘Nothing in life is guaranteed except death and taxes,’” Shah said. “It’s just such a part of life. No one can escape it, so we should be more open to talking about it, because it’s so real.”

Once a person reaches the end of their life, their family or hospice may hire a death doula to support the person and their loved ones through the emotions and logistics at hand. There were two death doulas in attendance at the Death Cafe, one being Nicholas Lance Bradley, 31.

Bradley, who is working on a doctorate in gerontology at UMass Boston, told the group that he believes he has the ability to sense when a person is about to die.

“If we’re speaking about my last client,” Bradley said. “I made eye contact with him, and it was like a rush over me that was like, ‘He’s gonna pass soon.”

Bradley is also an assistant teacher for a class called “On Death and Dying 101” and witnessed death during his childhood. He said avoidance and little information are part of what prevents death planning.

“In America, it’s less common for us to talk about death,” Bradley said. “There’s a lot of sadness associated with it, but there’s also a lot of lack of planning with it. I feel that it’s important for us to talk about it to normalize it and to make it less scary.”

Part of Bradley’s plan includes creating individualized videos for his loved ones every few years. He told the group that his loved ones know where to find these videos should he die suddenly.

“I’ve realized that a lot of people don’t really get to, one, say goodbye to their loved ones how they would like to, and, two, don’t get to hear how they affected their loved ones,” Bradley said.

The Fenway Death Cafe participants left that night with plates of leftover chocolate cake and suggested media from Lasky to continue their death education. She recommended a look into mortician Caitlin Doughty’s organization, Order of the Good Death; the book “The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning” by Margareta Magnusson; and the HBO show “Six Feet Under.”

“Whether you never go to a Death Cafe again, that’s your call,” Lasky said. “But maybe the name Caitlin Doughty, ‘Order of the Good Death’ will stick with you.”

Lasky said she took her daughter to a Death Cafe, after which her daughter hosted one of her own for students at her high school. According to Lasky, it was standing room only, and her daughter had to host another one to include the faculty.

“We don’t get very many opportunities in our lives to meet and open up so candidly with strangers from different generations,” Lasky said.

Note: All discussions in all Death Cafes are confidential. All interviews for this article were conducted outside of Death Cafes.

This article was produced for BINJ.News, the independent weekly magazine published by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism, and is syndicated by BINJ’s MassWire news service.