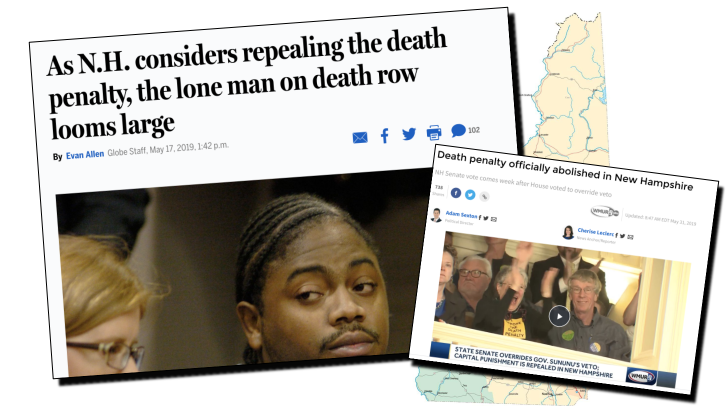

Michael Addison was barely 16 miles from the debate at Saint Anselm College in Goffstown, New Hampshire, on Friday night, where Democratic candidates had a few exchanges about race but said nothing significant about the criminal legal system. As the only man left on death row, an African-American in a state that is 93% Caucasian, sitting in the secure housing unit at the New Hampshire State Prison for Men, he seemed far from the concerns of the candidates on stage.

The New Hampshire Legislature abolished the death penalty on May 30, 2019, overriding a veto by Republican Governor Chris Sununu, and becoming the 21st state to end capital punishment. But the law was not made retroactive. Although the state has not executed anyone in 70 years and has no facility to carry out the death sentence, Addison is still technically sentenced to death for the murder of white police officer Michael Briggs.

The case raised numerous issues that still simmer beneath New Hampshire’s serene surface. There were twists in the case: Briggs’s partner came out against the death penalty after being counseled by Sister Helen Prejean, while other police officers argued, against all evidence, that abolishing the sentence would lead to the killing of police.

Addison was found guilty for intentionally killing Briggs in 2006. Some states make the intentional killing of a police officer a capital offense, and in most cases, according to 2017 research from Duke University, there is an outcry (and punishment) if a citizen kills an officer. However, research shows that “enhanced charges in police encounters are … asymmetrical. They only apply if a citizen harms an officer but not if an officer harms a citizen.”

According to the Death Penalty Information Center, “In 82% of the studies [reviewed], race of the victim was found to influence the likelihood of being charged with capital murder or receiving the death penalty, i.e., those who murdered whites were found more likely to be sentenced to death than those who murdered blacks.”

In spite of the fact more than 70% of the world’s countries have abolished capital punishment, those in New Hampshire who want the death sentence to stand are not happy that Addison’s lawyers are appealing the case. In an email, attorney Michael Wiseman of Philadelphia said he will not discuss the case, and one can only speculate that he is seeking what most states default to when they abolish the death penalty: life without parole. This means that there is no chance at an early release to serve the remainder of one’s sentence in the community.

The operative word here is chance. And this is what New Hampshire put on the books for all but Addison after it ended capital punishment.

Life with no chance of release is often called “the other death penalty”—it has been compared to being dead while you are still alive. According to the Washington, DC nonprofit, the Sentencing Project, the public could be better protected “by capping prison sentences at 20 years and investing in community building to prevent crime.”

But all that was nowhere to be found in Manchester on debate night. While presidential hopeful Bernie Sanders has said he is against the death penalty, it is not clear if he would insist on life without parole for Michael Addison or be nearly as progressive as any of the handful of his supporters I spoke with.

“In a way, I think life without parole is the same as execution” said Chicagoan Bridget Lynch. “You die in jail.”

Lynch, a Wellesley College student, arrived at 9 am on Saturday, filing into a packed Shoppers Pub in Manchester to canvass with hundreds of other Sanders supporters. Lynch noticed that the topic of justice was on the back burner at the debate, and said that everyone deserves a chance, an opportunity for parole, adding, “Our criminal justice system is going to continue this way until people like Bernie get in there and make changes.”

At Manchester Community College, where supporters were readying to canvass for their candidate, several were aware that Warren said on the debate stage that African-Americans were more likely than whites to be detained, arrested, taken to trial, wrongfully convicted, and receive harsher sentences.

Warren, however, has said on social media that she thinks the maximum punishment for people should not be capital punishment but instead death in prison. She would undoubtedly commute Addison’s sentence to life without parole. And while the Sanders supporters I interviewed would find that troubling, the Warren supporters I met had mixed responses.

When asked why candidates were not talking more about punishment and justice issues, Natalie Semel, a high school student from Connecticut, said: “To be honest, I think it has to do with where the first primaries and caucuses are held. Iowa and New Hampshire are very much predominantly white states and I think a lot of criminal justice issues affect people of color.” Semel made the trip to New Hampshire to canvass for Elizabeth Warren, although she rates Sanders a close second. She could imagine life in prison with a chance at parole for Addison.

However, another voter who told us his name is John, who drove up with his wife from Cape Cod, said he came because he “heard about this rally taking place and wanted to be more involved in the political process.” Although he didn’t want to speculate on the particulars of the Addison case, when asked about life without parole, he said, “as an alternative to the death penalty? Probably.”

The Campaign to End the Death Penalty (CEDP) would have another take on Michael Addison’s case. It is built on the philosophy that death row prisoners and their family must be at the center of fighting to abolish the death penalty—and CEDP may be the only anti-death penalty organization that opposes life imprisonment without parole.

This article was produced by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism as part of its Manchester Divided coverage of political activity around New Hampshire’s first-in-the-nation primary. Follow our coverage @BINJreports on Twitter and at binjonline.org/manchesterdivided, and if you want to see more citizens agenda-driven reporting you can contribute at givetobinj.org.