A growing body of research suggests that, in and around traffic, what you can’t see may be killing you

Every rush hour, thousands of cars belch out an invisible fog. Whenever a piston fires, a tire spins, or a car brakes, tiny flecks of soot, metal, and rubber are left behind, drifting in the air. Pedestrians on nearby streets, people by open windows, cyclists, and school kids breathe it in, unknowingly bathing their lungs in invisible pollution. Unlike dust or sand or smoke, this fog is too small for the body to notice or expel.

Boston’s terrible traffic is no secret. Every day thousands of cars, mostly from the suburbs, idle and crawl in near-gridlock on highways and “expressways.” A recent study bestowed Boston the dubious honor of “Worst Traffic in America.”

But stories about traffic tend to focus on the cost to drivers. While it is true that commutes have gotten longer and more stressful, focusing on commute times ignores the other costs of car-based transit. Research shows that living near highways and busy roads increases the risk of asthma, lung cancer, stroke, and heart disease. Highways are a health hazard. Vehicle emissions are sickening communities. People pay for traffic with their bodies.

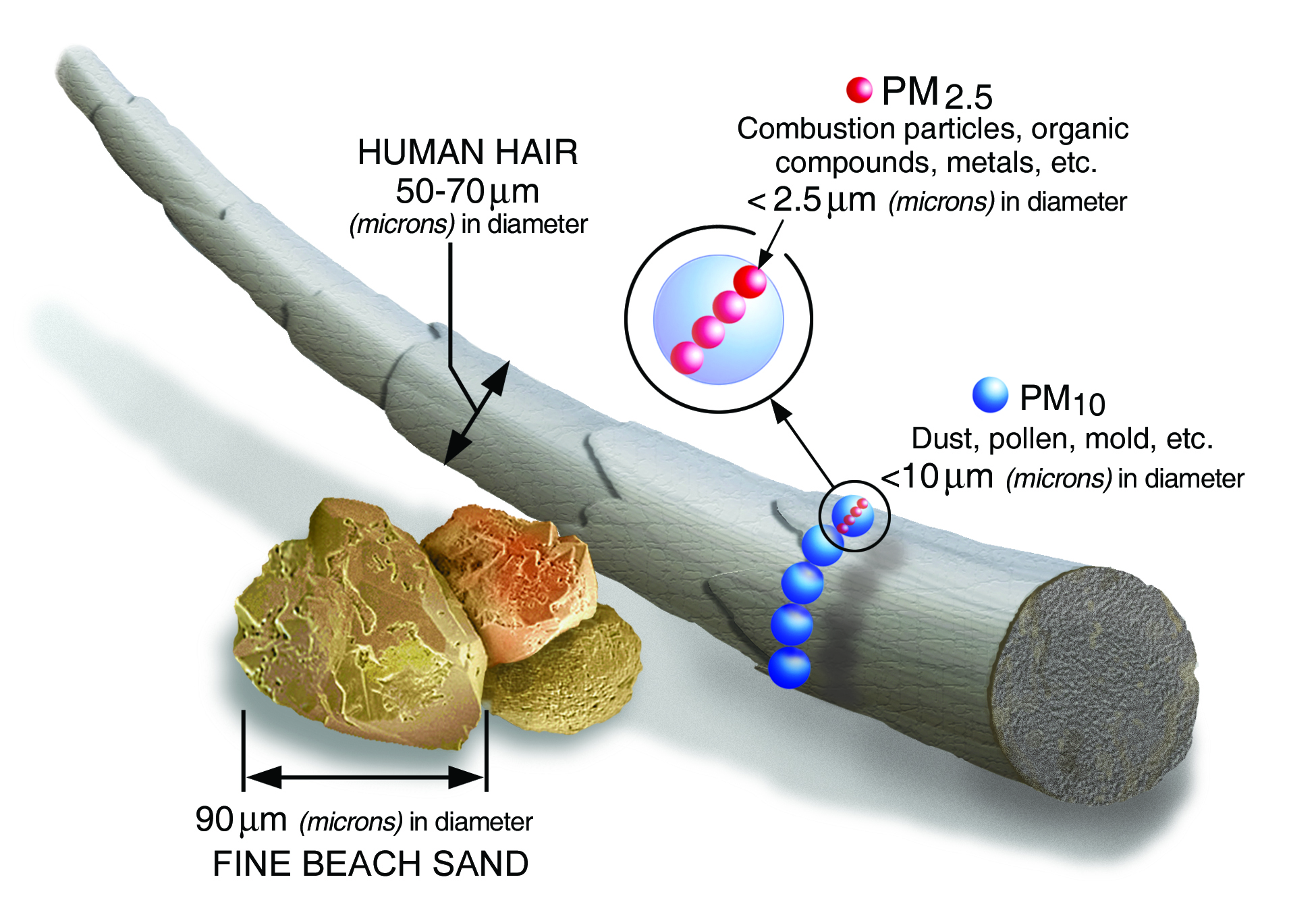

A growing body of evidence suggests that a newly discovered pollutant might be partially responsible. Ultrafine particles made of carbon soot, metal, and abrated tire the size of viruses have gone unnoticed. They’re difficult to study not just because they are small. Highway ultrafines are highly local and unstable, only travelling about 1,000 feet from the source.

The Environmental Protection Agency monitors air quality on a regional level, and Massachusetts is lumped in with New England. At that scale ultrafines, which are so volatile and unstable that only a network of local air monitors would be able to see them, disappear. Scientists study them using portable samplers mounted to vans, bikes, or exteriors of buildings, and what they’ve found is deeply troubling.

Fuel, pistons, and tires

In the early 2000s community researcher Wig Zamore unearthed a worrisome trend in Commonwealth public health records. At the time, Zamore was serving on the Steering Committee for the Metropolitan Area Planning Council as they developed a new regional plan.

“It became immediately apparent that I93 was a large environmental health and justice issue. Everyone else got transit. Somerville got the Red Line T Stop in Davis, but mostly highway and diesel rail pollution,” he explained in an email.

Fourteen communities in the Boston metropolitan area had far higher rates of death by heart attack and lung cancer than average. Towns like Somerville, Chelsea, and Revere had 75% more deaths from heart attacks or lung cancer. The pattern held even when adjusted for age and other cofactors.

When Zamore mapped the data, a startling picture emerged.

“By and large it looked like a highway map,” he explained. People living near the highway were having heart attacks and contracting cancer more often than their neighbors. Zamore wasn’t alone. A study in Stockholm found that living near a highway increased heart attack risk by 69%.

When a car or truck drives a lot of things are happening at the same time. Fuel ignites. Pistons and other moving parts scrape each other. Tires rub the pavement. Brake pads rub against the rotor. Exhaust escapes the tailpipe. Ultrafines are made at every phase of this process, but the majority of them come from tailpipes. Hot gasses react with the cooler air outside and condense into tiny, invisible, particles made of mostly carbon, heavy metal oxides, sulphate, and nitrate.

The colder the temperature, the more ultrafine particles are made. These particles are so tiny that they don’t act like other particles; they diffuse like gasses.

“They don’t have enough mass to hit something,” said Doug Brugge Professor of Community Medicine and Healthcare at UConn. Brugge is one of the principal researchers in the Tufts Community Health Assessment of Freeway Exposure and Health (CAFEH) studies, which examine the effect of ultrafine pollution on people living by highways. He explained that ultrafines drift through the air and stick to whatever they touch. Once stuck to a hard surface, ultrafines aggregate into a sooty layer that you might see on a sound barrier by the highway.

When inhaled, ultrafines settle in primarily in the upper airways or deep within the lung. They diffuse through the protective mucus of your airways and are so small they avoid capture by immune cells. Some travel up the olfactory nerve into the brain. Some remain in lung cells. Others circulate in the blood and get embedded in vascular or organ tissue. Once inside and circulating, ultrafines collect near cellular mitochondria, which can kill or damage cells. They also release heavy metal contaminants that damage cells. Sensing widespread damage, the immune system activates, searching for an injury.

But there isn’t one. Unlike after an infection or injury, ultrafine inflammation never resolves. Chronic systemic inflammation ensues which increases the risk of lung cancer. Blood pressure increases. Veins and arteries are damaged. In the CAFEH study, Brugge and his colleagues found elevated blood pressure and increased inflammatory markers in people living by I-93 in Somerville and Chinatown. In animal studies, ultrafine exposure was found to cause atherosclerosis, and arterial plaques. Brugge likens it to chronic obesity.

“It [obesity] would be associated with a similar kind of low-grade chronic inflammation and lead to similar outcomes,” he explained. Like obesity you don’t necessarily experience symptoms but the damage to the heart and lungs accumulate slowly over time.

The degree of that damage isn’t completely clear. A soon-to-be-published study by the California Air Resources Board hopes to settle things. The study will include 20 years of health data correlated to ultrafine exposure models developed at UC Davis. A spokesman for CARB emphasized that demonstrating systemic inflammation wasn’t enough. “The actual endpoint is cardiovascular disease. We want to make that connection concrete.”

In the brain the effects are strange and more subtle.

“Air pollution has been associated with cognitive decline,” said Debora Cory-Slechta, a professor of environmental medicine at the University of Rochester. She explained that many neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s had been associated with elevated iron levels in the brain.

“It might just be going up our noses over the course of our lifetimes,” she said.

The nerve

Cory-Slechta researches how ultrafine particles affect the brain. She exposes mice and rats to ultrafine pollution collected from a nearby highway to see how it changes brain development in the long term, and has traced the movement of ultrafine particles into the brain up the olfactory nerve.

“You see brains loaded with iron, sulfur, and copper,” she said, “Once it gets in the brain it doesn’t appear to ever leave.”

Long-term exposure causes neural cell death, degradation of the corpus callosum (the connection between the right and left halves of the brain) and markers of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Cory-Slechta cautions that the precise relationship between ultrafine particles and the brain isn’t fully understood. There’s a lot that still needs to be clarified, but “there’d be nothing preventing the EPA from developing that regulation, other than the current administration,” she remarked.

At least one local lawmaker isn’t waiting for the EPA to step in. Massachusetts state Rep. Denise Provost filed two bills this year to address ultrafine pollution. HR 1989 would charge the Department of Public Health to review and map all particulates in the state; HR 1990 would require that schools and residential areas within 500 feet of a highway get mitigation through filters, retrofits, or barriers. The bill faces an uphill battle in the legislature.

“I’m not optimistic,” said Provost, who represents Somerville. “It’s very technical information and it’s hard to communicate it effectively.”

Other local lawmakers are also fighting to protect their constituents. Matt McLaughlin, the Ward 1 councilor in Somerville, has been pushing to get sound barriers installed. Sound barriers can catch a lot of ultrafine particles, but he too is facing trouble. The Massachusetts Department of Transportation only installs barriers in very specific circumstances and East Somerville, in spite of the noise and pollution complaints, doesn’t make the cut.

“I just don’t think they care,” McLaughlin said. “It’s not a priority for them. It’s easier to ignore it.” It’s a longstanding problem for Somerville.

“If you go back and look at the history of highways and trains everything was made to cut through us,” he said.

Violent by design

Somerville and Chinatown face some of the worst congestion in the state: 262,000 vehicles pass through Somerville on I-93 and McGrath Highway daily, while more than 300,000 vehicles pass by Chinatown, which is ringed by I-90 and I-93. These are the most densely populated communities in Massachusetts, which makes them far more vulnerable to ultrafine pollution.

In some ways this is by design. Highways do not happen by accident. In The Folklore of the Freeway, professor Eric Alvia of UCLA writes, “Highway planners found the paths of least resistance, wiping out black commercial districts, Mexican barrios and Chinatowns.”

These highway projects were part of a broader movement of urban renewal and “slum clearance” that came from earlier patterns of housing discrimination. The Federal Housing Authority in 1935 formalized racial discrimination in home lending through a process called redlining, in which the presence of immigrants, African Americans, or poor people was often enough to disqualify the neighborhood from getting federally backed mortgages.

On maps, such areas were outlined in yellow for “declining,” or red for “hazardous.” In Boston, the West End, North End, South End, Chinatown, and Roxbury were redlined. Almost all of Somerville was marked as “declining” or “hazardous” aside from Tufts University, while the communities with the “lowest value” would face highway development and demolition for the next 80 years.

“This was not a natural or organic process,” explains LaDale Winling, professor of history at Virginia Tech. “What we think of as good neighborhoods had help. What we think of as bad neighborhoods had the power of the federal government against them.”

Somerville and Chinatown exemplify this trend. During the 1960s a coalition of activists protested and defeated the inner belt highway project that would have carved up Cambridge, Brookline, Roxbury, and the more affluent part of Somerville. In 1970, Governor Francis Sargent called a moratorium on highway construction and diverted the funding to expanding the Red and Orange lines. But the moratorium came too late for Chinatown, which lost half its land and one third of its businesses to the turnpike.

In Somerville, the I-93 was grandfathered in. Protestors rallied and demanded a safe highway be built, and under the provisions of the newly passed 1970 Clean Air Act, community advocates forced the Sargent administration to conduct an environmental impact assessment of the elevated highway plan. But while the study found that the elevated highway would violate the Clean Air Act, exposing Somervillians to lead, carbon monoxide, and toxic benzine, construction went on anyway. Further efforts by Somerville activists to mitigate noise or air pollution were stonewalled, and East Somerville became an island ringed by I-93 and McGrath Highway.

Fifty years later, the people of Somerville and Chinatown are still paying for I-93 and I-90. Ironically, gentrification, which threatens them in a different way, has spread the health burden of highway air pollution to the most affluent. Some of the most expensive developments are going up by highways.

“It’s a very sad form of democracy,” Rep. Provost said.

“We do feel that MassDot owes the community,” explained Lydia Lowe, director of the Chinatown Community Land Trust. She explained that while calls for electric cars or expanded public transit were positive steps, more needed to be done in the short term to mitigate air pollution. The CAFEH study group, meanwhile, is working with the mayor of Somerville to develop air-filtration guidelines for homes by highways. They also hope to remodel highway-adjacent Foss Park to block pollution. In Chinatown, the Chinese Progressive Association is pushing for similar things, but these efforts will come to nothing if the state doesn’t step in.

The communities along the highway know what they need—barriers, protective green spaces, and air filters. They are not willing to wait for the rise of electric cars or decades-long investments in our decrepit transit infrastructure. Every day of exposure exacts a toll on their health. Every rush hour these communities shoulder the burden of our car dependence.

“Now that we have ways to mitigate the impact of air pollution,” Lowe said, “we’d like to see a situation where government plays a stronger role in making that happen.”