Part 2: What do we do?

The City of Somerville’s buildings, roads, sidewalks, water distribution, and sewer systems are all at or near the end of their lifespans. A cogent memo to the City Council last spring detailed our infrastructure needs and estimated their costs. Its implications obligate reconsideration of basic assumptions guiding land-use policy in this city with severe constraints on developable land.

The few elected officials who have taken public notice of the report appear to have drawn inaccurate conclusions. The first is that the $1.1 billion repair-and-replacement costs explicitly stated in the memo define the size of the challenge.

That amount would be daunting by itself. It is several times our total current bonded debt. And now we must bond the new high school ($130 million plus overruns) and the new public safety building (estimated at about $100 million).

But $840 million of the $1.1 billion is only what we need to invest now to prevent emergencies and meet code requirements. Bringing our infrastructure to nominal condition with such an investment would still be inadequate to achieve the city’s goals, as championed by elected officials, specified in the city’s comprehensive plan, and supported by most residents. To accomplish that would require a multiple of $1.1 billion. Richard Raiche, the memo’s author, did not attempt to estimate the multiple’s size.

I have also heard some City Council members say that we have fifty years to complete and pay for the required work. But the memo’s fifty-year figure refers only to how long we have to reconfigure our water distribution system to meet long-term goals.

Our need to counter generations of deferred maintenance of our water distribution and all other infrastructure systems is immediate, as those systems disintegrate before our eyes. The time horizon to reconfigure our systems depends upon whether and when elected officials intend to achieve their stated housing, economic development, urban design, public-space, mobility, and sustainability goals, all of which require modern infrastructure.

The city’s just-concluded election campaign confronted a few candidates with a question about how to fund this investment. Those who responded cited the $77.5 million of American Rescue Plan Act funds coming to Somerville. But all $77.5 million would be less than five percent of what is needed, and diverse interests are already vying for a portion of those monies.

The Commonwealth’s strictures on how cities finance themselves leave property taxes as the only means for us to pay for renewed infrastructure. If we don’t want to drive out all but the most affluent homeowners and renters, we can’t drastically increase residential taxes. And at current tax rates, residential properties lose the City money, even though they constitute 84% of assessed property value, as opposed to 66% for Boston and 59% for Cambridge.

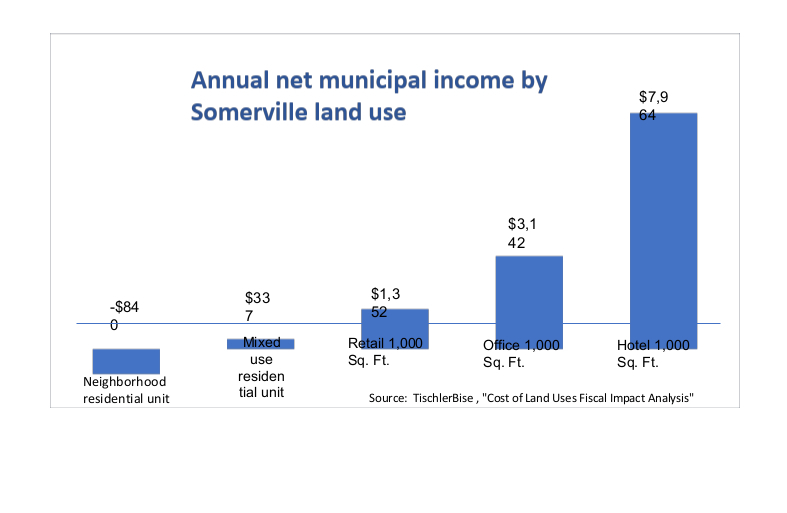

The following graph summarizes the only study done of net property tax income by land use—what properties pay, minus the cost of providing city services to them.

City officials directed Carson Bise to use a marginal-cost approach and to exclude from this analysis costs of debt on the new high school, the new public safety building, and all other new infrastructure. With more accurate assumptions, each of these net-income estimates would have been lower.

So virtually all residential property produces a net loss. Yet production of largely unaffordable housing increased the residential proportion of property valuations between fiscal years 2014 and 2021.

If lab space had been included in the analysis, the average annual return per 1,000 square feet would be about $5,000, as lab space is costly and lab equipment is taxed. And right now we are enjoying a land rush by biotech developers. Something like fourteen major office and lab buildings are in the development pipeline. Indeed, this fiscal year’s tax base went up by 10%, and the current City budget depends upon $20 million in one-time building permit fees and adds forty new positions.

But those very development projects have shown that we cannot rely on our Comprehensive Plans’ land-use assumptions if we want to maintain affordability and fiscal health. The first SomerVision plan designated five areas in the city as transformation districts, estimated the amount of developable land in each, and set a goal of 60% commercial and 40% residential development, by square footage.

We are now learning that mobility infrastructure in four of these areas’ cannot support the level of development anticipated and therefore creates the need for a greater commercial land-use allocation. This is becoming apparent first in Boynton Yards. The area can only be entered by Medford Street and Webster Avenue, which both become glacially-moving parking lots twice a day.

So zoning now limits parking spaces to 1,500 for the entire district. Yet one developer of 6.5 acres has absorbed 1,200 spaces. Even though all those spaces must be open to the public, interest by developers in Boynton Yard’s properties—once intense—is dropping off.

City mobility staff are working to demonstrate that continued development there is a matter of persuading developers that the Green Line, shuttles, and bicycles will make projects viable. Their efforts are laudable. But the people who must be convinced are those who are unwilling to give up their cars or who have no choice but to drive if they want a job and a family.

Another concern is that most developers who have the capacity to build lab space are now looking for viable locations wherever they can find them. The regional market may become saturated before potential Somerville sites become persuasive of their viability. However, the presence of a nascent enviro-tech cluster here may eventually attract those who develop property for that industry and its sustainability-conscious tenants.

If our elected leaders have any hope of keeping our city affordable, much less accomplishing the goals they have embraced, they must think systemically. They must avoid the many temptations to spend on cool and innovative programs, investing in need-to-do projects now so as to create capacity for nice-to-do projects in the future.

They must maximize commercial development. They must ban above-ground parking in the transformation areas, thereby benefitting both the City and developers, as Somerville land values now make above-ground parking a foolish waste.

When city officials determined that requiring underground parking in Union Square’s Green-Line block would cost developer US2 an additional $13 million, US2 got a pass on a seven-story, 345-foot-long parking/residential structure that will barricade the neighborhood for generations. Given current land values, building more compact commercial space above underground parking there could have netted US2 many times that amount in profit, and a lot more tax revenue for the city.

Our leaders must seriously rethink the Comprehensive Plans’ land-use assumptions, including the commercial-residential mix in the transformation districts, in certain blocks within our commercial centers, and near all transit nodes. Regarding the latter, evidence is clear that residents are willing to walk longer distances to transit nodes than employers are willing to locate jobs from them.

Despite these imperatives, planning staff is hustling neighborhood plans for Assembly Square and Brickbottom that are based on the old land-use assumptions. The Assembly plan even assumes a 50/50 residential/commercial mix. And some staff members have encouraged at least two developers to hasten their permit preparation and file before the new City administration and Council can take office.

Their stated rationale is that housing development is needed to make the transformation districts 18-hour-per-day neighborhoods. They are right. Mixed-use neighborhoods offer greater security. But this can be achieved with substantially less than a 40% housing mix.

A second rationale is that we need to house those who would work in the new commercial spaces. But the workers are already here. The last time that the U.S. Census studied Somerville residents’ journey-to-work, it found that 85% of us must leave the city to go to our jobs. In fact, our skilled workforce is an essential factor that attracts commercial developers.

Most city officials no longer defend the baseless claim that boosting largely unaffordable housing production in New England’s densest city will somehow lower prices in what is a fragment of a regional market.

Increasing the proportion of land zoned for commercial development is also a key factor in meeting that other greatest challenge—maintaining and expanding housing affordability. That is the subject of the final column in this series.