“The Public Records Law strongly favors disclosure by creating a presumption that all governmental records are public records.”

That language appears in nearly every determination issued by Massachusetts Supervisor of Public Records Manza Arthur, an appointed official who serves as the chief records officer under Secretary of the Commonwealth William Galvin. But at the Department of Public Health, the presumption appears to run in the opposite direction—especially when journalists come calling.

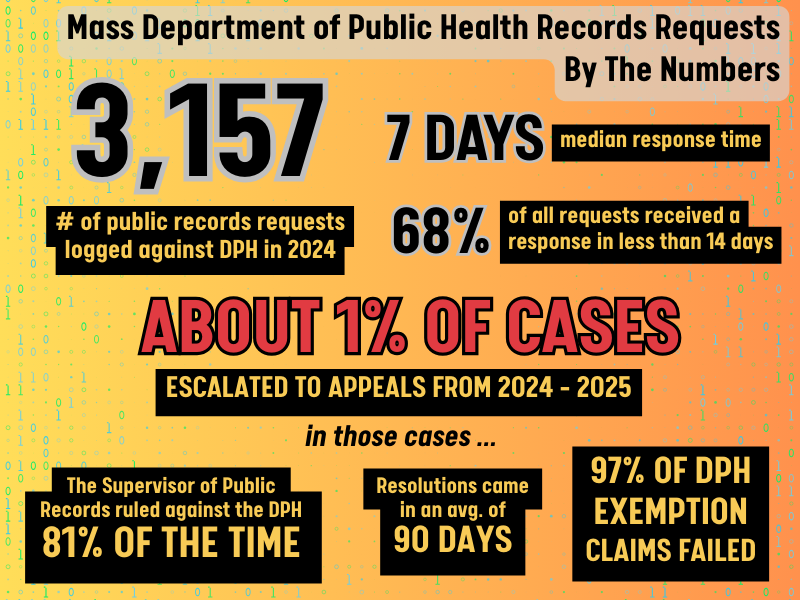

An analysis of 69 public records appeals filed against the DPH over the past two years reveals a pattern of delay and obstruction that stands in stark contrast to the agency’s routine handling of requests. While the department responds to most inquiries in about eight days, appeals take an average of 97 days to resolve. The supervisor of public records ruled against the DPH in 81% of those cases; when the agency claimed an exemption to withhold records, it succeeded less than 3% of the time.

In one determination issued in December 2025, the Department of Public Health informed BINJ reporter Jacob Schles: “Since you are considered media, our reviewed records for both requests have to go up to the communications office for review and approval before they can be released to you.”

No such review is authorized under Massachusetts law. The public records law requires agencies to respond within 10 business days. Records access officers are not allowed to require a requester to state the purpose of their request except to determine if the requested records are made for a commercial purpose, or to grant a request for a fee waiver.

In another case, a reporter for the Washington, DC-based Capitol Forum waited nearly three months for inspection records on rehabilitation hospitals. The department blamed the delay on its media relations team, which had been “taking an inordinate amount of time to read through the responsive records and redact them.”

A third case revealed that internal review processes can operate beyond the control of records staff. The “timeline is not within the control of the Bureau’s public records team,” the department told a reporter for the New Bedford Light seeking nursing home records.

That reporter, Grace Ferguson, filed seven separate appeals against the Department of Public Health in 2024 and 2025. In each case, the supervisor of public records ordered the department to respond.

The pattern extends beyond the aforementioned inquiries. Alec Ferretti, a researcher seeking records, has filed 33 appeals against the DPH and various municipalities over what he describes as “a proxy war” with the state.

“The [supervisor of public records] SPR ostensibly agrees with me that no exemption actually exists,” Ferretti told BINJ in an email. “However, because the SPR is essentially unwilling to order anyone to produce records, and instead, simply orders them to take another bite at the apple, we’re now on collective round 33 of Let’s try to find another reason to deny Alec.”

Accountability in the shadows

The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press said the state health department’s pattern is troubling.

“The spending/dispersal of settlement money tied to the national opioid lawsuits is of tremendous public importance,” according to Gunita Singh, a staff attorney for the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. “The opioid epidemic has touched millions of Americans and the press and public have a right to understand the full contours of this litigation, including the aftermath.”

Singh continued: “It’s unfortunate—and violative of the letter and spirit of the law—that the [DPH] has chosen silence and obstinance over compliance and responsiveness.”

Justin Silverman, executive director of the New England First Amendment Coalition, said the situation at the DPH is not unique.

“Various government agencies slowwalk requests or ignore them so they don’t have to release information they don’t want to,” Silverman said. Adding, “More broadly speaking, the issue is enforcement.”

“If those in government aren’t following the laws themselves and are working in secrecy,” Silverman said, “then we don’t know how the decisions that affect us are being made.”

Taking legal action is of course extremely costly and time-consuming, especially for independent media. BINJ contributor Andrew Quemere of the Mass Dump recently scored a big win for transparency, with a judge ruling that the Northwestern District Attorney must release names of cops charged with crimes. But the fight was an extraordinary effort, assisted by the director and students from Harvard Law School’s Cyberlaw Clinic.

So much for compliance

The delays documented in SPR determinations often continue even after the supervisor orders the department to comply.

Despite repeated orders from Supervisor of Public Records Manza Arthur’s office to provide a response for two different records requests filed by BINJ—one in early September, the other in mid-October 2025—the DPH only continued to state that the records were “under review” until BINJ made a request for comment on this article.

In November, the supervisor ordered Rush-Lloyd to respond to a request from this reporter for municipal opioid settlement spending data collected through a state database. When the department missed the 10-business-day compliance deadline, Arthur’s office issued a compliance notice, again ordering the department to respond. Two weeks later, Abigail Kim, policy director for the Bureau of Substance Addiction Services, which is part of the DPH, told BINJ that the records were “still under review.”

On Jan. 13, in response to a request for comment on this article, Kim said, “all of your requests are working their way through our approval process.”

The following day, 90 days after the original request, the DPH finally provided the records: an Excel file and a single PDF. But the response came with a caveat. “Please be advised that the data being shared is preliminary and subject to change,” an accompanying letter stated. “The Department strongly cautions you regarding the accuracy of any analyses based on preliminary data.”

The meaning of the warning is unclear, but public health officials have used similar disclaimers to shirk accountability before. Last November, the Executive Office of Health and Human Services told BINJ that a separate report (filename: “FY25 ORRF Annual Report – Signed.pdf“) was a “draft”—only after BINJ questioned why it did not account for $13 million in expenditures.

State law requires that report, of the Opioid Remediation and Recovery Fund, to be presented by the EOHHS secretary to the legislature and made publicly available no later than Oct. 1. To date, neither has happened.

A rogue ‘review process’

The DPH determinations analyzed for this article span requests on topics ranging from nursing home inspections to pharmacy board investigations to vital records. In nearly every case, the supervisor found that the department had violated the 10-business-day response requirement under Mass law.

In total, 3,157 public records requests were logged against the Department of Public Health in 2024. The median response time was just 7 days (including weekends), and about 68% of requests received a response in less than 14 days.

But the 69 cases that escalated to appeals across 2024 and 2025 tell a different story: of exemption claims that fail 97% of the time, of “administrative review” processes that operate outside the law, and of a communications office that adds an extra layer of delay for journalists.

“If those in government aren’t following the laws themselves and are working in secrecy,” Silverman said, “then we don’t know how the decisions that affect us are being made.”

The New England First Amendment Coalition has established a litigation fund for public records cases. But Silverman acknowledged the limits of that approach.

“Even so,” he said, “the system is broken in many ways.”

Ed. Note: A previous version of this article mistakenly attributed words to a Department of Public Health official that they did not say. On Oct. 17, 2025, the department did tell New Bedford Light reporter Grace Ferguson “the administrative review process timeline is not within the control of the Bureau’s public records team.” Additionally, the article has been updated to reflect that Ferguson filed seven appeals related to records sought over the span of two years. We regret the error.