In a recent interview, Shawn Fisher, formerly incarcerated in Massachusetts, questioned why there is so little interest in parole. He served 32 years for second-degree murder, and is now paroled with a job and his own apartment.

“People are unaware of the parole process and the parole system,” Fisher said, “and by not being aware, there’s no care.”

People call parole “early release,” he noted. They generally don’t understand that parole is the earned and conditional release of prisoners to the free world where they live under strict supervision for the remainder of their sentence. Parole requires a prisoner to prove to a parole board that they are no longer a risk to society.

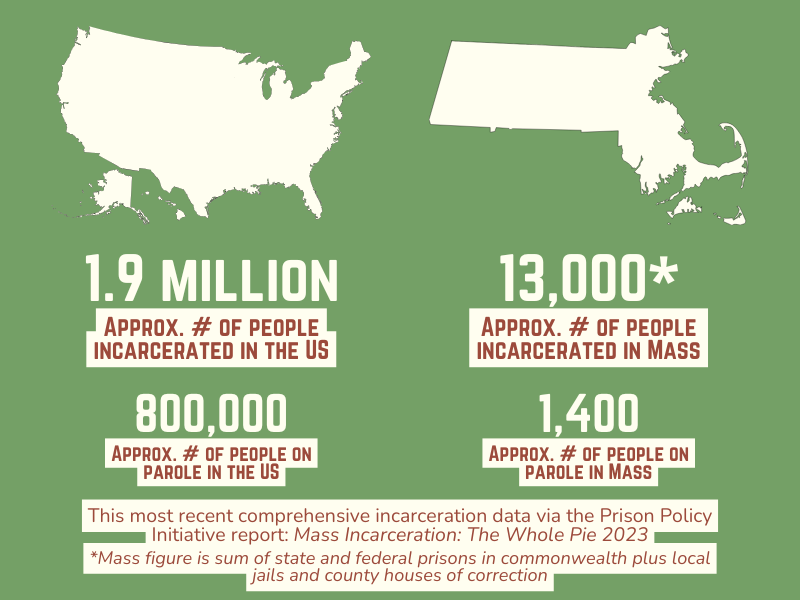

Only about 800,000 people in the US were on parole in 2023, reports Prison Policy Initiative (PPI), a nonprofit research organization based in Mass. More than three-and-a-half times times that amount, or nearly 3 million people, were on probation in the same period. PPI’s stats in that year for Mass list 38,000 on probation with 1,400 on parole.

While the numbers are low, parole is a significant opportunity for a person who has been locked up for decades to reunite with family.

Nate Benjamin was paroled in August 2025 because of the landmark court decision, Commonwealth v. Mattis, which ruled those in Mass under 21 can no longer receive life sentences without the possibility of parole. He’d been sentenced to life in prison for first-degree murder, and told the Parole Board that he shot his victim without intention to kill. Benjamin said he feels “an enormous amount of sadness for my victim’s family,” coupled with “enormous gratitude.” “For the last 30 years of my life,” he said, “I dreamed of having a second chance.”

BINJ set out to investigate if second chances are still possible, why there is such little public understanding of parole, how misinformation floods the news, and what Massachusetts petitioners are currently facing because of ignorance and indifference.

A recent history of clemency in Mass

In 2024, Mass Gov. Maura Healey issued blanket pardons for those with misdemeanor marijuana possession convictions, which the Governor’s Council then approved. A pardon removes the underlying conviction.

The current governor issued 21 other pardons by April 2025, as well as new clemency guidelines that seemed to promise a progressive administration. Parole advocates hoped that the former prosecutor might actually encourage her Parole Board to step up clemency applications—in Healey’s own words, to center “fairness and equity in the criminal justice system.”

Since she took office in 2023, though, the current governor has not approved any petitions from the other arm of clemency—commutations, which are reductions in sentences. In comparison, Gov. Charlie Baker before her approved three commutations, an uptick from previous governors. And, according to the Boston Bar Association, from 2003 to 2007, Gov. Mitt Romney granted zero commutations from 2003 to 2007, while Gov. Deval Patrick granted one commutation, in 2015.

Healey’s selective silence

There is also the governor’s actual impact on the body itself. Ten months ago, we wrote about the seeming lack of interest in the Parole Board shown by Healey’s office.

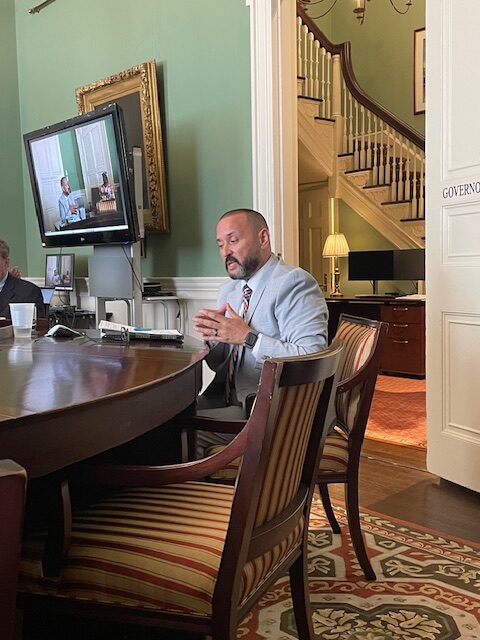

After former Parole Board chair Tina Hurley submitted her resignation in April 2025, it took Healey a month to appoint Angelo Gomez to the vacancy on the board, and another five months to name him chair. Tonomey Coleman, meanwhile, served as acting chair after Hurley. In July 2025, he became an associate district court judge. Since then, Healey has still not appointed a seventh board member.

The governor has not addressed criticisms of her management of the Parole Board, but she recently spoke publicly about one particular prisoner’s status.

Jose Colon was 20 when he killed a state trooper in 1983 and was convicted of first-degree murder. The 63-year-old, who became eligible for parole as a Mattis case, told the Parole Board at his hearing, “My crime was inexcusable. I’m ashamed of what I did.” He had little access to programming for much of his time in prison, according to a psychologist who evaluated him, and as reported by MassLive, “relied on his faith for self-development and rehabilitation.”

WBUR reported that in what is an uncommon practice, Healey urged the Parole Board to reject the release of Colon. In a statement, the governor wrote that she opposed his parole because of the “nature of this offense, the magnitude of its harm, the welfare of this state, and the enduring public significance of Trooper Hanna’s sacrifice.”

A new barrier to parole

The Gomez nomination was divisive from the start. Some contended he would continue Hurley’s progress; others questioned his “priorities.”

In December, two months after Gomez became chair, MassLive reported that, “for the first time in a decade,” the Parole Board issued no decisions on life sentence cases, leaving families and petitioners adrift through the holiday season.

Attorney Patricia Garin runs the Northeastern University School of Law Prisoners’ Rights Clinic, which trains parole attorneys. She told BINJ that as chair, Gomez recently instituted a new policy regarding hearing procedure which is a barrier for those seeking parole.

In Massachusetts, lifer parole release hearings are open to the public. The practice for years has been to allow the prisoner and their attorney, if they have one, to share the opening statement. After the opening, each member of the board questions the petitioner. Up to five witnesses can then testify for the applicant, and up to five against. A joint closing has also historically been possible for the petitioner and their lawyer.

Under Gomez, the board has limited the decades-old policy and required that either the person seeking parole or their attorney deliver the opening and the closing. Garin told BINJ this will slant the focus of the hearing away from the rights of the petitioner.

“An opening statement is an extremely important part of a parole hearing,” Garin wrote in a statement to BINJ. “This new procedure makes it impossible for parole petitioners to apologize directly to victims at a public hearing and also exercise their right to have their attorney make an opening where complex issues can be explained to the board. This is a huge step backwards. I am hopeful the board will reconsider this process.”

A flailing Parole Board goes unnoticed

As prior BINJ reporting previewed last May, six Parole Board members are now juggling a herculean job, waiting for the governor to act. Relatedly, suggestions for Healey to add more members to the board through executive action have gone unheeded.

As a result, since April 2025, the board has limped along, and the rate of release for those who seek parole is down in Massachusetts. This means that people are serving longer sentences.

Research has shown that parole enhances public safety. Those on parole supervision commit few felony crimes—about 5%. Parole also deflates mass incarceration, and is a safety measure as well as a strategy to shorten long sentences. By a margin of two to one, victims of crime prefer a system that centers rehabilitation rather than punishment. It’s a proven way to keep people accountable for harm they have caused while delivering justice. This holds true for both those with life sentences and those without.

When Tina Hurley was board chair, her rate of release for non-lifers in houses of correction or state prisons was 67%. That was not significantly higher than under board chairs in the years before her tenure.

For those with life sentences, in 366 decisions under her leadership, Hurley released 241, or 65.8%. That’s more than her predecessors—Chair Glorianne Moroney (456 decisions/45.6% grants), and Chair Paul Treseler (392 decisions/26% grants).

While Tonomey Coleman was temporary chair after Hurley’s departure, his rate of release over five months for 54 life-sentenced petitioners was 50.1%. As of this writing, there is only a small sample of 12 posted lifer decisions under Angelo Gomez’s chairmanship.

The impact of a stretched Parole Board

Parole Board appointees are consistently overworked. Members are consistently expected to read hundreds, and sometimes thousands of pages related to applicants serving life sentences prior to hearings. According to the agency’s own 2023 annual report, the full body conducted 133 life sentence hearings that year. Two days a week, they travel to prisons and houses of correction throughout the state, and in 2023 held 3,100 institutional hearings individually or in groups of two or three.

Adding to their workload, in addition to reviewing petitions for both commutations and pardons, the board conducts hearings to terminate supervision for those with successful parole histories. In 2023, the board weighed 51 requests for termination and held 19 hearings. With a board stretched at the seams, the Parole Board has yet to issue its 2024 annual report. However, between January 2024 and February 2025, the body held only eight termination request hearings.

Gorden Haas, a lifer at MCI-Norfolk who annually details the parole process in Mass, wrote in his 2024 report that, under Healey, the “time delay” between hearing dates and dates of decision was 97 days. According to Betsey Chace, a researcher who keeps relevant stats, the time delay under Tonomey Coleman increased to four-and-a-half months. There are no meaningful time delay stats yet on Gomez’s board.

Legislatively, there has been no fix for the overburdened board. That despite several bills which were submitted last year for the current legislative session to increase its size and thus reduce workload. They include: H.2694, An Act to promote equitable access to parole, and H.1812, An Act to promote timely access to parole hearings. A briefing on these bills to underscore their importance was held in March 2025. Neither made it out of committee.

Misinformation, fueled by the press

Reportage in the mainstream media contributes to the public’s skewed perception of the parole process.

As formerly-incarcerated prison journalist Kerry Myers spelled out in an observational piece for the nonprofit Marshall Project, “journalists are uncharacteristically incurious, substituting easy-to-get official statements for answers to more relevant questions the public might have.”

Starting with the region’s newspaper of record, BINJ examined all mentions of “parole” in the Boston Globe from February 2024 through January 2026. Out of 15 articles, nine were about specific parole hearings. Six focused almost exclusively on the crime of conviction, with headlines suggesting that prisoners have not changed. Examples include: “Man Who Killed Parents, Sister, Denied Parole Again;” “Man Who Killed Teen in 1995 Robbery Gets Parole;” and “Convicted Murderer, Rapist Denied Parole.”

These articles lead with the crime, often mention prosecutors protesting parole, and omit programs that the prisoner has undertaken behind bars and the testimony of people who vouch for him. They also ignore statements of remorse, and focus almost entirely on the written decision posted by the Parole Board. Only one of the other three articles leads with remorse from the petitioner. It includes an interview of the parole attorney, addresses what the prisoner accomplished behind bars to rehabilitate himself, and at the end, details the crime. That particular article was about a parole hearing in New Hampshire.

At the Boston Herald, of 20 articles including the word “parole” in 2025, 13 covered specific hearings with an even stronger focus on the crime than the Globe. Headlines include: “Massachusetts illegal immigrant paroled after murder grabbed by ICE at jail,” and “Massachusetts convicted murderer who said ‘What’s up now, sucker?’ before killing man has been granted parole.”

The Herald is also prone to pontificating. A quarter of the paper’s mentions are editorials pushing anti-parole statements and denigrating the board and those who seek clemency. For example: “An increasingly progressive justice system sees criminals as victims, and victims are inconsequential,” and “The Massachusetts parole board was at it again last week, releasing Jody Oleson — who was 25 when he was out on parole and bludgeoned a 71-year-old man to death.”

Last February, Plymouth County District Attorney Timothy Cruz bylined an editorial emphasizing his anger regarding “decisions granting parole to murderers were released just before Christmas, delivering undeserved joy to convicted murderers.”

Now that Kerry Myers of the Marshall Project is out of prison, he interprets the relationship between much of the media and those in power thusly: “What’s clear from watching the news or reading a paper from the other side is that a complicity has developed between media and the criminal-justice apparatus that contributes to bad policy.”

As for the impact of that complicity and press neglect … In 2019, Prison Policy Initiative took a broad look at how parole systems were “relatively ignored by the public and the law.” They graded all 50 states, specifically gauging if an apparatus gave “every incarcerated person ample opportunity to earn release and have a fair, transparent process for deciding whether to grant it.”

PPI determined, “Only one state gets a B, five states get Cs, eight states get Ds, and the rest either get an F or an F-.”

Massachusetts got an F.