The setup of the situation is absurd, the stuff of cable dramas about government bureaucracy and crooked cops. Yet it’s standard operating procedure in Massachusetts.

First, there is the fact that there are police working in the Bay State who have been charged with crimes like domestic assault and possession of child pornography.

Then there is the common practice of law enforcement leaders shielding their offending colleagues from any real repercussions or public embarrassment. This even as district attorneys maintain so-called Brady lists of bad cops whose past problems could undermine their credibility in court.

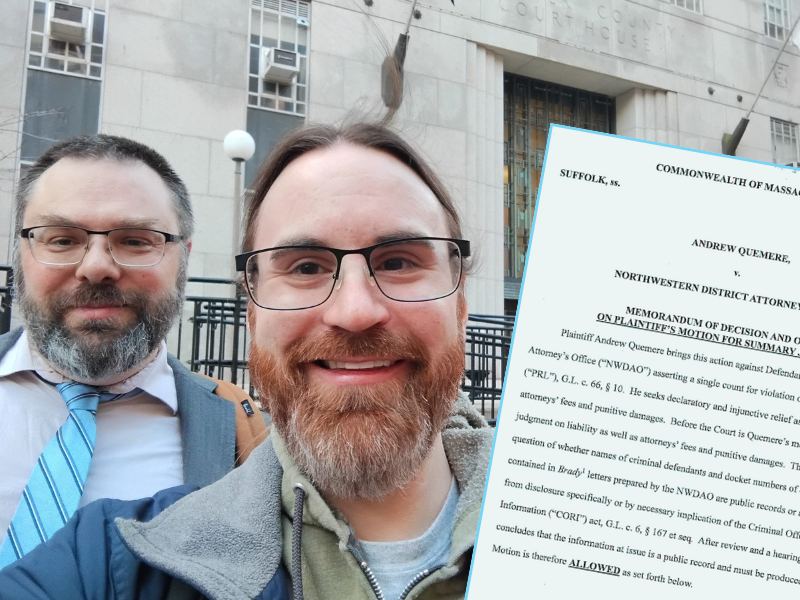

In an attempt to punch through the commonwealth’s blue wall of sleaze, which remains a public records hurdle despite ballyhooed POST Commission reforms, investigative reporter Andrew Quemere requested the contested Brady information from the office of Northwestern District Attorney David Sullivan in January 2022. That led to three administrative appeals with the state’s supervisor of public records, all of which Quemere won, and a lawsuit, and spurred the next outrageous aspect of this story—Sullivan hired outside counsel to defend the opacity. According to public records, he spent more than $16,000 in taxpayer money on this case to protect troubled cops.

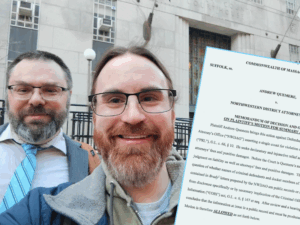

The DA’s costly defense didn’t work though. As Quemere, who runs the Mass Dump and has written for BINJ, reported on Tuesday: “On December 30, nearly four years after the Dump first requested the records, Suffolk County Superior Court Justice Julie Green ruled that the names and case numbers were not protected and that Sullivan’s office must disclose them.” He continued:

“Sullivan’s office provided copies of the Brady disclosures but blacked out the names of officers who had been charged with crimes, citing the state’s Criminal Offender Record Information (CORI) law. His office also removed docket numbers that were associated with the officers’ criminal cases and with the cases in which the officers were potential witnesses. …Green ruled that releasing the officers’ names and case numbers is not prohibited by the CORI law because all the information can be found in public court records and releasing it would not allow anyone to compile the officers’ complete criminal records.”

Quemere and the Dump were represented pro bono by attorney Mason Kortz and his students from Harvard Law School’s Cyberlaw Clinic. Kortz said in a statement: “This ruling preserves the purpose of the CORI statute—to prevent people from obtaining wholesale criminal records outside of the proper channels—while also allowing for meaningful public accountability. … We hope that other district attorneys will abide by this ruling if they receive similar requests in the future.”

A spokesperson for the Northwestern District Attorney’s Office provided the following comment to Quemere about the ruling and potential for subsequent action: “We are pleased the court found that we acted in good faith in attempting to prevent the unlawful disclosure of Criminal Offender Record Information (“CORI”). We continue to review the court’s decision to determine whether to pursue an appeal. Given the pending litigation, we cannot comment further at this time.”

You can read Quemere’s full recap here.