ILLUSTRATION BY NATASHA ALTERICI USED COURTESY OF A WAVE NEW WORLD

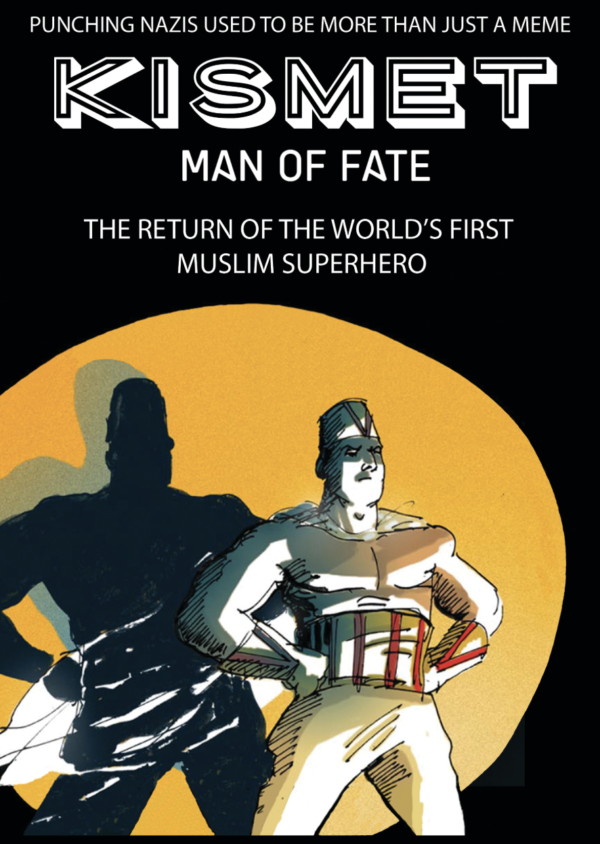

How America’s first Muslim superhero surfaced in Boston after 70 years in retirement

A sweep of headlights brings the sign into view: “Boston, 1 Mile.”

The car speeds under the elegant pointed arches of the Zakim Bridge, and then into the I-93 tunnel under downtown Boston. Inside, obscured by shadows, the driver swears at the erratic motorists ahead of her. Thus enters Boston’s hometown superhero, coming to save the day.

If a Boston superhero brings to mind a tired Wahlberg or Affleck trope—set in Southie, crawling with cops and mobsters, topped by bad accents—you are likely not alone. However, Kismet, Man of Fate, is almost the exact opposite of the Hollywood manufactured Boston caricature.

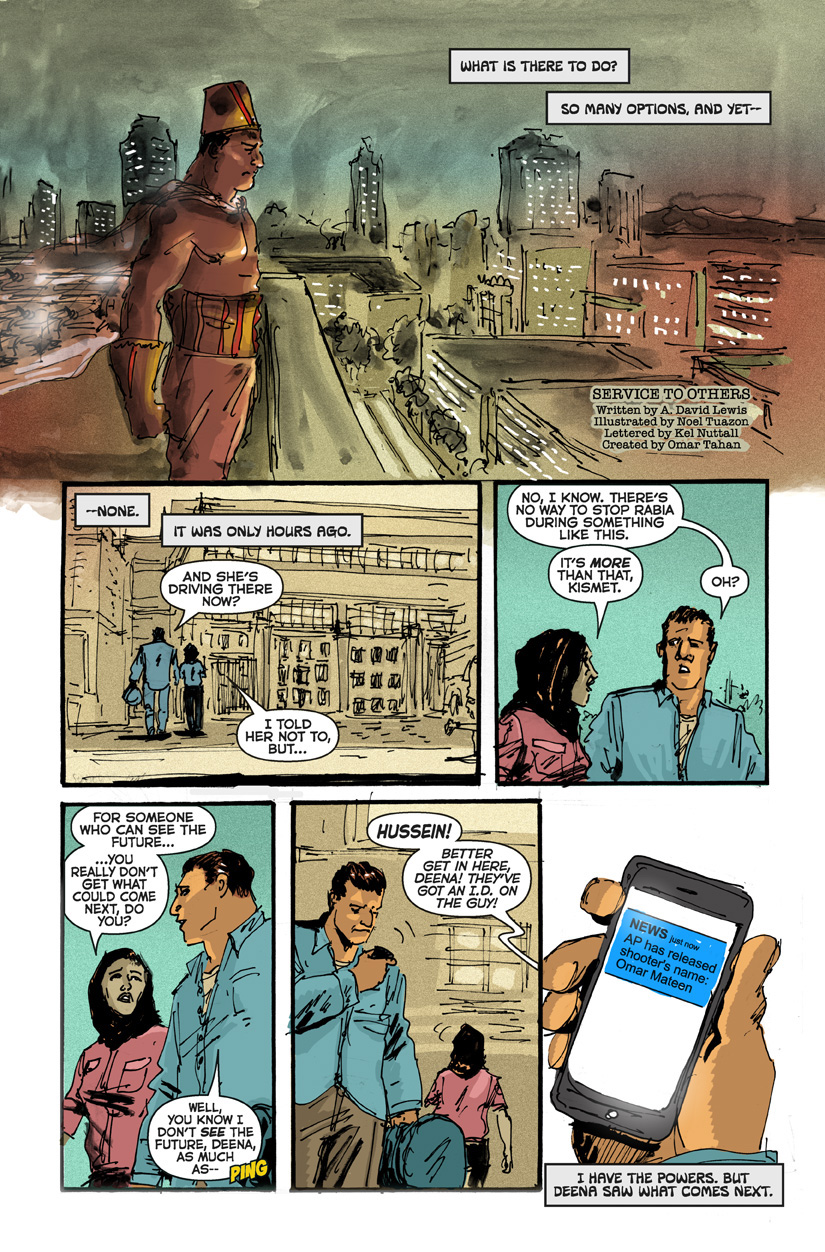

The character of Kismet, revived and reimagined by local author and academic A. David Lewis, is an Algerian Muslim with two queer Muslim women as his non-super sidekicks. Early on in the story, he eschews violence in favor of social and political action. He wears a silly hat. He is also completely and comfortably a Bostonian, saving the day not by flying in from above, but rather commuting via I-93 and a sea of Masshole drivers.

Like many Bostonians, Kismet is a transplant. The character first appeared in a brief run in Bomber Comics in 1944, fighting Nazis in Vichy France and punching Hitler for fun. Lewis first encountered Kismet in 2007, when he went looking for the first Muslim superhero as part of his research for a scholarly volume on religion and graphic novels. According to Lewis, this title belongs to Kismet. Some artists featured Arab characters in graphic novels prior to that, but they were either not overtly Muslim or not overtly “supers.”

Kismet only appeared in four volumes before his character was dropped. Eventually, his likeness and stories reverted to the public domain, allowing Lewis claim and revive the character. Lewis, who is a convert to Islam, was drawn to the character not only because he was the first Muslim, but because his story and identity were handled with a sensitivity not often seen in popular culture at that time, or indeed even today.

“His “Muslim-ness” wasn’t overblown; his faith seemed to just be part of his character, not some overwhelming trait,” Lewis told me in an interview in 2017, shortly after he first reintroduced the character. “I saw a lot to like in Kismet that, frankly, I found lacking in a number of Muslim superhero depictions over the years, especially with the way Dust from the X-Men comics has been handled at times.”

We don’t know with certainty the name or names of the writers who first developed Kismet. The author listed for the series was a pseudonym, but according to Lewis’s research, the most likely candidate was a woman named Ruth Roche. Roche, like Lewis, was a native of Massachusetts. Thus it is all the more fitting that Lewis, rather than creating a fictional city for Kismet to settle in, or returning him to southern France or his native Algeria, transported him to contemporary Boston.

We don’t know with certainty the name or names of the writers who first developed Kismet. The author listed for the series was a pseudonym, but according to Lewis’s research, the most likely candidate was a woman named Ruth Roche. Roche, like Lewis, was a native of Massachusetts. Thus it is all the more fitting that Lewis, rather than creating a fictional city for Kismet to settle in, or returning him to southern France or his native Algeria, transported him to contemporary Boston.

Lewis chose Boston for a host of reasons. The rising Islamophobia in the wake of the bombing of the Boston Marathon first planted the idea that the region needed a Muslim superhero. The depth and complexity of the Hub’s history, and present, also played into the decision. Home of the Revolutionary war, abolitionists, and busing riots, Boston is a “perfect paradox that encapsulates the history of the entire United States,” Lewis told the Dig. As importantly, Lewis was tired of New York having all the fun. “I felt I was giving Kismet a home and giving my home a hero,” Lewis told me in 2017.

Kismet fits contemporary Boston where, according to the 2010 census, more than 28% of the population was born outside the United States. Because of Lewis’ intimate knowledge of the city, Kismet’s Boston feels like Boston. He provides a wealth of details—from quoting city ordinances about fire sprinklers in buildings, to referencing in-jokes like the 2007 Mooninite bomb scare. Kismet attends some of the most defining events of the past few years in Boston, like the Muslim-Ban rally in Copley Square.

Perhaps as important as the color in the storyline, Kismet’s artwork captures Boston’s architecture and geography. Disparate landmarks like Marsh Plaza at BU, Boston City Hall, and the Swedenborg Chapel in Cambridge are all depicted in his unique style. Characters in Kismet don’t just walk around the block from Boston City Hall and find themselves in Cambridge. They have to deal with awful drivers and crowded trains like the rest of us.

There are small details as well. MBTA buses and wood-clad triple-deckers quietly and naturally inhabit the backgrounds of each scene, while the color scheme also reflects Boston. The daytime city scenes are dominated by browns ranging from golden brick to coffee; the blue-black night that rules for half the year also features prominently, punctuated by points of light from the skyline.

Though Kismet’s Boston may feel strikingly familiar, fictional but nearly parallel universes can give both natives and transients a chance to view their city on unfamiliar terms. Speaking to the Guardian, Warren Ellis, author of the London-set graphic novel FreakAngels and other beloved books, observed that in comics, “spires become watchtowers, the top of pubs become gardens, churches become secular gathering places. We interact with them through the comic in a much more intimate way than we ever interact with them as residents or tourists.”

During the course of Kismet’s adventures, we are not only allowed into spaces that are otherwise off limits to most residents, like the stacks of Harvard’s Andover Library, but also the private space, both physical and mental, of the characters in the story. The same Guardian piece argues that urban settings are the almost universal, defining feature of comics, not only because “cities—as places that ferment action and opportunity—are obviously a great source of narrative for comics. But perhaps the connection is even deeper. There’s as much action to be found in the private world of urban living as there is spilling out on to the streets.”

Boston is not known for being a minority friendly city by a long shot, but according to the 2010 census, 53% of its residents identify as something other than non-Hispanic white. Ironically, in real life Kismet would be counted among the 47% of non-Hispanic white Bostonians. Controversially, people of Arab descent are considered white for purposes of the census.

Kismet is one of a few isolated examples of fictional depictions that focus on the experience of Bostonians who don’t identify as white and male. According to Carlo Rotella, professor of American Studies at Boston College, Boston has “become synonymous with not just the idea of the local but with a very specific kind of locality: the imagined neighborhood worlds of working-class white ethnic guys who inhabit what’s left of an industrial-era Boston that’s been disappearing for at least two generations.”

In Kismet, readers are introduced to a diverse array of characters in every sense of the term. His closest associates are two queer Muslim women, one devout and one not so much. Another character proudly introduces herself as “half Boston Irish, quarter Tibetan, quarter black.” Kismet sits down for an interview about his powers with real-life African-American theologian Jacqueline Lewis. All while the story’s two main antagonists are a middle-aged woman and an older man, of French and Algerian origin respectively.

We meet most of these characters in their intimate spaces and see them as fully-fleshed out, complex human beings. The characters who in Kismet’s Boston are almost all women and/or racial, religious, and sexual minorities. The story provides a glimpse into the lives of minorities among minorities… and shows them to be completely mundane.

Fiction, whether it takes the form of film, novel, or comic, is a camera obscura—a pinhole image that helps us isolate and focus on isolated aspects of reality. A single story featuring characters from historically marginalized groups, like Kismet, does not “solve” Boston’s problem fictional representation, but can help as they become more of the norm, and not just the exception.

“Telling and sharing diverse stories adds to the cultural landscape of the city,” Cagen Luse, graphic designer and founder of the group Comics in Color, told the Dig. “It peels back the formulaic Boston tropes and reveals the diverse and colorful Boston I see everyday. I believe this will result in people of color seeing themselves represented as an important part of the fabric of this city.”