For developers in Boston, it may pay off to blow off inclusionary building requirements

It was another condo building rising in Southie. The development at 135 Athens Street/160 West Broadway was approved by city officials in 2014, with the promise that two of its 15 units would be affordable.

The building was finished in 2017. But when the Boston Planning and Development Agency (BPDA) reviewed the completed project, it discovered the developer had sold the units that had been designated for affordable housing at market rates.

Something had to be done.

The solution: a fine that likely still gave developers a profit margin, and the permanent loss of planned affordable units.

While investigating the 135 Athens development, BPDA officials discovered three other projects that failed to comply with agreed-to affordable housing requirements.

Beyond that, the agency says it hasn’t found any other projects in violation, and it claims to now have stricter policies. But housing advocates say the BPDA’s reaction doesn’t address the crushing need for affordable space in the city and indicates a lack of concern about the problem in the first place.

“Everybody was asleep at the switch,” said Steve Meacham, a housing watchdog and organizer who works with the Jamaica Plain-based nonprofit City Life/Vida Urbana.

“How much does that failure represent a headlong pursuit of development at all costs?”

The deal

Records show that developer Leah Popielarski proposed the project in 2014 and purchased the property at 135 Athens St that year for $1.8 million through the company Black Flat LLC. The Boston Redevelopment Authority—several years before its six-figure rebranding as the BPDA—approved it through its “small project review” process for projects of 15 units or more that are smaller than 50,000 square feet.

The initial plan called for 15 condos—nine one-bedroom one-bath units at about 750 square feet; two two-bedroom 1.5-bath units at about 920 square feet; and four two-bedroom, two-bath units between 930 and 1220 square feet. The four-story building would also include a parking garage for 20 cars.

Boston’s inclusionary development policy requires large- and medium-scale developers to create affordable units on- or off-site based on the amount of total units developed, or to contribute money to the city’s affordable housing fund for future projects. According to BPDA documents, Popielarski agreed to provide two “affordable” units—one set for a buyer at 80 percent of the city’s area median income (AMI), and another set for between 80 and 100 percent—but did not specify whether the affordable units would be one or two bedrooms.

AMI, which is determined by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development, varies by household—in 2017, the AMI for a two-person household in the metro Boston area was $82,7000, while for a four-person household it was $103,400. And that in turn leads to variance in the rental and condo prices for the city’s affordable housing agreements, even as the percentages in agreements negotiated by the BPDA remain the same.

In 2017, when the project completed construction, the sales price of a one-bedroom condo at 80 percent AMI was $180,000, and the sales price of that same condo at 100 percent AMI was $239,000. A two-bedroom condo at 80 percent AMI would have cost $214,000 and one at 100 percent AMI went for $277,000.

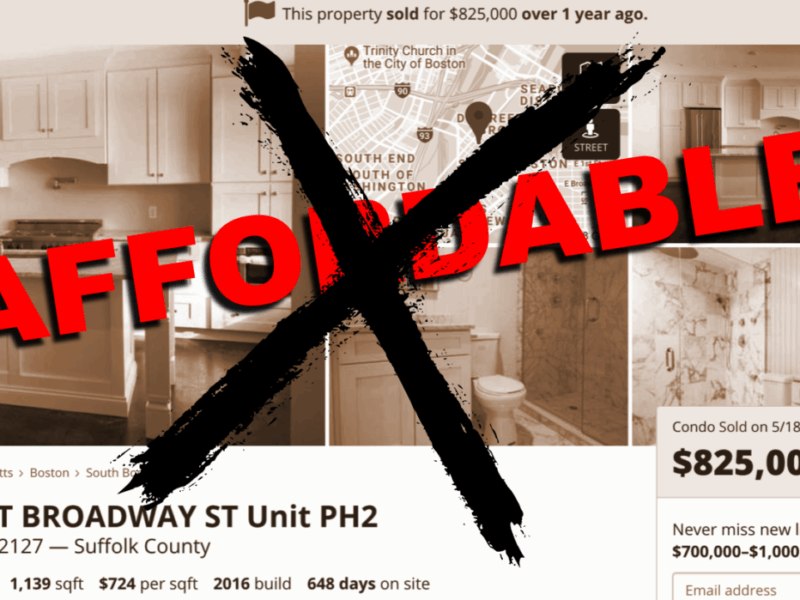

Those numbers are well below what Black Flat was able to sell the units for at market rate, according to information from the Registry of Deeds. The lowest-priced unit sold for $564,000, while the highest-priced sold by Black Flat went for $825,000.

Black Flat sold all 15 units between March and May 2017, according to the Suffolk County Registry of Deeds. But the last two units were not sold to homebuyers on the open market or affordable applicants—they went to Seaport Residential, another company formed by Popielarski, for $10 apiece. Seaport Residential sold those last two units at the end of June for $625,000 and $853,000.

All told, the 15 units sold for $9.95 million, an average of $664,000 a unit.

Leah Popielarski, the property owner and project developer, could not be reached for comment. Ryan Connelly of RMC Development, who is listed as Popielarski’s contact in BPDA documents, said he was involved in the project “at first but not any more,” and did not respond to additional requests for more information on the development or on contacting Popielarski.

Discovery and fine

When construction of a large project of 50,000 or more square feet is finished, the BPDA must issue a certificate of completion before the project can move forward with renting or selling units. That gives officials the ability to check in on the project’s affordable housing plans, and projects with affordable units are required to go through city channels to market those units to prospective buyers.

But the 135 Athens project never submitted a marketing plan for the units it later sold at market rate. BPDA officials said they discovered the lack of affordable housing when transferring information about developments to a new database.

Not filing the marketing plan and selling the units at market rate meant the project was not in compliance with its affordable housing agreement, and potentially subject to legal action. In this case, the BPDA approved a new affordable housing agreement and a settlement per which the developer will pay $600,000 to the city’s affordable housing fund—$200,000 by Nov 20, $200,000 by the end of the year, and $200,000 by the end of next March.

The penalty for violating the AHA was a fine of either the minimum affordable housing contribution per unit in the development’s geographical area—for 135 Athens, $300,000 per unit—or half the differential between the BPDA’s determination of the affordable price for the units and their full market value. The first set of figures was larger, leading to the $600,000 settlement.

At an October BPDA meeting, housing policy manager Tim Davis said the BPDA’s calculation of $600,000 was based on newer data than had been in place when 135 Athens was approved, increasing that payment from $425,000 and adding a “penalty.” The BPDA board approved the settlement unanimously, with member Michael Monahan saying the agency came out ahead.

“In hindsight, it’s better off that they did violate it—we get more money,” Monahan said.

On the other hand, considering the sale prices, one could also conclude that it was financially prudent to violate the agreement. The BPDA would have set strict limits on the sale prices of affordable units for households at 80 percent and 100 percent of AMI. Depending on whether those units were one or two bedrooms, the units combined would have sold for between $419,000 and $491,000, according to 2017 standards.

Compare that to the average sale price of $664,000 for one unit of the 135 Athens project at market price, or $1.32 million for two units. Subtracting the $600,000 fine still leaves the developer with $732,000—at least $230,000 more than what the affordable units would have sold for.

Also, while affordable units are usually restricted for at least 50 years when they are created, violating the affordable housing agreement created two units than can continually be flipped or resold at market rate.

“It sets a terrible precedent if that’s the consequence,” said Helen Matthews, a City Life spokesperson. “It doesn’t manifest the immediate affordable housing that’s needed. It’s all part of the story of BPDA’s sloppy supervision of this issue.”

BPDA spokeswoman Bonnie McGilpin said the agency’s transfer of information on its developments to a new database will prevent other projects from reneging on their affordable housing commitments, and that BPDA compliance staff are checking all building permits pulled through the city’s Inspectional Services department to confirm it has affordable housing agreements.

“BPDA has improved communication with the Office of Fair Housing to check during construction that developers have engaged Fair Housing regarding marketing plans,” McGilpin said in a statement. “Recent project approvals have also required that developers contact Fair Housing upon receiving building permit. … As a result of these changes, an Article 80 project with an IDP commitment does not have the ability to move forward without a completed affordable housing agreement.”