The Hub’s most elite high school has been under growing scrutiny for its apparent neglect to properly address a culture of racial intolerance. While federal investigators probe that issue, this story of a former Boston Latin School student with special needs raises additional points of concern about another minority population at BLS.

It was near the end of October 2014 when Christina Smith*, a sophomore at the prestigious Boston Latin School (BLS), was first questioned by Headmaster Lynne Mooney Teta, Assistant Headmaster Malcolm Flynn, and a detective from the Boston Police Department.

The detective, Christina recalls, interviewed her once in the presence of Flynn and Mooney Teta. In another instance, she was questioned by Flynn and Mooney Teta without the detective present, later by Mooney Teta one-on-one, and once more in a separate meeting with Flynn.

Christina’s mother, anonymized throughout this article as Mrs. Smith, says her daughter was spoken to or questioned four times in the span of two weeks. The inquisitions stemmed from an alleged campus sexting incident, and centered around Christina’s best friend at the time and two other students — a boy and a girl.

At the time, Christina was also undergoing an evaluation for an Individualized Education Program (IEP) to address recent traumatic episodes, panic attacks, and her Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Despite having qualified for the elite exam school, she had a history of difficulties that sometimes affected her learning.

At the time, Christina was also undergoing an evaluation for an Individualized Education Program (IEP) to address recent traumatic episodes, panic attacks, and her Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Despite having qualified for the elite exam school, she had a history of difficulties that sometimes affected her learning.

During the investigation, Christina told her parents that she was asked to give up the name of a male student who was supposedly disseminating pornographic images and videos of classmates. Due to the information she provided, other students were also pulled into the dragnet.

“I was friends with a girl [a student that was] allegedly raped,” Christina recalls, adding, “She told me about it. I told [school administrators and detectives] about that.” As a result, Christina says she was interrogated about everything from BLS culture to specific individuals.

Spokespeople from the City of Boston and Boston Public Schools (BPS), as well as BLS administrators, were asked to comment on the Smith case, but did not respond to calls or emails sent by BINJ, the latter of which included specific questions about the allegations herein.

By early November 2014, Christina had become a social pariah. She was having trouble sitting through lessons and could barely bring herself to go to school in the morning. She refused to participate in class. According to the Smiths and as suggested by documents obtained by the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism, through the bullying, some of Christina’s teachers as well as BLS administrators refused to formally acknowledge her anxiety. She received zeros for not presenting projects in class, and instructors began to view her as a disinterested pupil who couldn’t hack the famously advanced BLS course loads. She was given multiple detentions and even suspended.

“They thought I was ditching for the hell of it,” Christina says.

Reported over the course of more than a year, this is a detailed account of how a student with special education needs was apparently forced out of BLS rather than cared for. As documents and interviews reveal, Christina didn’t slip through the cracks so much as she was pushed. By September of 2015, she would be attending one of the two other exam schools in the district, a transfer instigated by BLS administrators who offered to wipe Christina’s disciplinary record clean — as long as she left the school for good.

TOP CHOICE

BLS, America’s original public school, is not a modest institution. Its motto is “Sumus Primi,” Latin for “We are first.” Like other high schools, BLS has a hall of fame. Unlike other places of elite learning, said tribute features homecoming heroes including John Hancock, Ben Franklin, John Adams, and more recently, power and industry honchos like Sumner Redstone.

The school’s prestige and tough curriculum attract Boston’s wealthier families, a number of whom send their children to private school through the sixth grade (BLS starts in seventh). At the same time, middle- and lower-class parents see BLS as a ticket to boundless opportunities, perhaps even a pathway to Harvard University. In any given year, it’s common for the exam school to send more than a dozen graduates across the Charles River for an Ivy League education. Commenting about the school’s impossible standards on the chatty family listserv, one individual claiming to be a BLS parent summed up the culture in a way that effectively paraphrased the sentiments of several people interviewed for this story:

I honestly don’t understand the constant concern surrounding the amount of hard work and homework it takes to succeed at Boston Latin. Quite frankly I am surprised that there are parents that want to ease the competitive level at the school. Surely everyone knew of the reputation and intense academic environment of Boston Latin before taking the test to enter the school. Boston Latin’s high standards and intensity is the reason the school has the excellent reputation and respect around the country … I think it is bad judgement to water down the standards or ease the workload. If some children cannot handle the environment perhaps they should go to a school that is more nurturing rather than trying to change the standards and culture at BLS.

As a standout bright spot in the BPS system, BLS relies on prestigious national rankings and on its reputation among Boston’s well-to-do families, generations of which have contributed to an endowment worth nearly $40 million. Christina’s failing grades, as well as the rumors of sexual misconduct and bullying among students affiliated with her, posed threats to the school’s reputation. The fact that Christina’s parents couldn’t afford private tutors, or handle her psychological issues without help from school administrators, made a bad situation worse. Her father, who has Asperger’s syndrome and became fixated on airing his grievances publicly, added to the drama by addressing alleged school sex scandals on the BLS family listserv ad nauseam, accumulating countless community foes in the process.

As a standout bright spot in the BPS system, BLS relies on prestigious national rankings and on its reputation among Boston’s well-to-do families, generations of which have contributed to an endowment worth nearly $40 million. Christina’s failing grades, as well as the rumors of sexual misconduct and bullying among students affiliated with her, posed threats to the school’s reputation. The fact that Christina’s parents couldn’t afford private tutors, or handle her psychological issues without help from school administrators, made a bad situation worse. Her father, who has Asperger’s syndrome and became fixated on airing his grievances publicly, added to the drama by addressing alleged school sex scandals on the BLS family listserv ad nauseam, accumulating countless community foes in the process.

According to the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Behavioral Health Barometer, about 39,000 Massachusetts adolescents (8.1 percent of all adolescents) per year had at least one “major depressive episode” between 2009 and 2013, with that number on the rise in the past half-decade. But situations like Christina’s are uncommon at BLS. According to BPS data from the 2014–2015 school year, Latin School has disproportionately fewer students with recognized disabilities (1.4 percent) and fewer students considered to be economically disadvantaged (19.4 percent) than the district as a whole. Of the 54,000-plus BPS students, 19.5 percent have recognized disabilities, while 49.3 percent are considered economically disadvantaged.

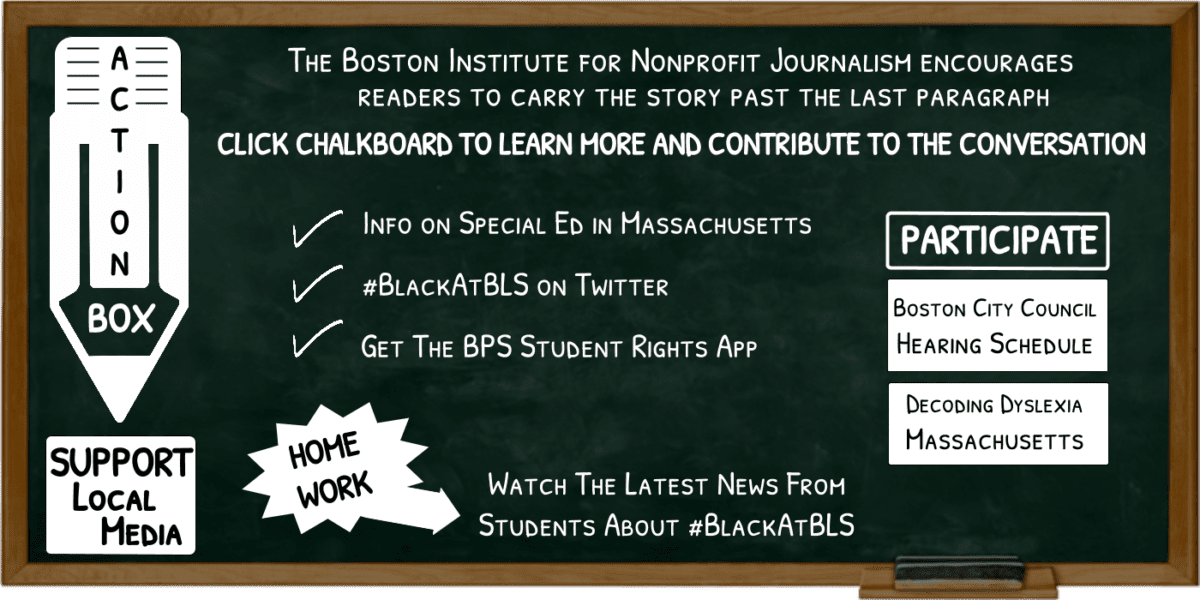

At a recent Boston City Council budget hearing, aid for students with special needs was specifically addressed, with the frustrations many families have with the system laid bare in public testimonies. Scott Bishop, the father of a grade schooler receiving special accommodations, worried that proposed cuts for next year will “decimate things that some may view as optional, but [that] for our daughter and others like her are vital to her growth and development.” Another parent at the hearing, Liz Gomez, said she fears what shifts in funding will mean for her autistic son in BPS, while Roxbury City Councilor Tito Jackson lamented cuts that will affect “the students with the biggest hurdles.”

Karen Kast-McBride, a BPS parent of three students with special needs and an outspoken district activist for more than two decades, said, speaking of the overall system, “Boston is one of the best places in the world for special education.” When it comes to specialty schools like BLS, however, Kast-McBride is less quick to issue superlatives. Too often, she says, students with special needs are not given proper accommodations. Kast-McBride continues, “It’s almost like they think, because they’re an exam school, they can get away with it.”

Which makes students like Christina minorities among minorities, special cases occurring in small numbers that require extraordinary attention.

PRIVATE MATTERS

When Christina was two and a half years old, she was referred to early intervention due to concerns associated with language delay, social skills, attention, and a “scattered development profile.” The following year, she was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome. After that she received home services, including Applied Behavior Analysis and speech instruction from an occupational therapist. Christina was placed on her first Individualized Education Program (IEP) soon after and subsequently “consistently tested as academically bright and made significant progress during the next several years,” according to a copy of Christina’s health records furnished by her family for this story. In the third grade she was fully mainstreamed into the general BPS population. According to her documented history, Christina was removed from her IEP because she “no longer met the clinical criteria of Asperger’s.”

By the time Christina earned admission to BLS she was something of an anomaly — an overachiever with a history of learning disabilities. The family of Nancy Duggan, a founding member of the Massachusetts chapter of Decoding Dyslexia, a group raising awareness at the state level about people with learning disabilities, has been in a similar position. Duggan says her daughter, now in her early 20s, was a “bright and articulate” child who was memorizing books outright, as opposed to learning how to read the right way, through the third grade. “She was smart enough to skate by,” Duggan says, adding that her daughter’s natural intelligence kept her from getting evaluated properly.

A similar phenomenon seems present at BLS, where some students interviewed for this story say they or their friends have avoided getting tested for learning disabilities to avoid being stigmatized. As a result, they say, while certain BLS teachers dedicated to special needs students are both passionate and helpful, for those left untreated, disabling conditions can escalate. “I know so many people who go to BLS who are mentally ill,” says one recent graduate. Speaking of a friend, she adds, “There’s something wrong with a school where someone leaves senior year because they can’t take it anymore because of their mental illnesses. There’s something wrong with a school where a 13-year-old wants to kill herself because she didn’t do perfectly on a Latin test. BLS is pretty messed up, to be honest.”

In her case, Duggan eventually took matters into her own hands and says she used her family’s savings to send her daughter to a private school in Worcester at a cost of $20,000 a year. Duggan says that for children with disabilities who aren’t adequately recognized by public schools, like her daughter and Christina, private education is essential. “If [a student] isn’t receiving accommodations by the third or fourth grade,” Duggan says, “they’re not going to graduate.” High-stakes testing like MCAS, she says, has “changed the dynamic.”

Duggan’s daughter went on to attend the prestigious Trinity College in Connecticut. Years later, she says her family was “lucky” to avoid a prolonged battle over their public school system’s mandate to provide special education. Others have been less fortunate.

LATIN LIMBO

In practice, school districts, not individual schools, are responsible for meeting a student’s special education needs and providing a free and appropriate public education. BPS is therefore tasked with allocating the funds for special education programs. Due to Boston’s weighted budget policy (and because of state and federal guidelines), special needs students require extraordinary individualized funding. BLS has very few such pupils (fewer than 2 percent of the 2014 student body received special services); so when BPS found itself facing a $100 million budget gap in 2010, Latin School was hit especially hard, receiving a 5.1 percent cut in funding — more than double the 2.5 percent cut proposed across the entire district. John McDonough, the BPS chief financial officer at the time, said the measures were taken to save money for “special needs students and non-native English speakers, who aren’t in large numbers at Boston Latin.”

As a result of funds being redirected to special education and ESL students, more than 20 Advanced Placement classes stood to be cut, with music, theater, and Chinese on the chopping block as well. BLS Headmaster Mooney Teta was vocal about how she believed the boost for Bostonians with learning disabilities would impact her campus. “Every year, we invite 420 of the brightest students to cross our threshold from every neighborhood and socioeconomic strata in Boston,” she told reporters at the time. “We tell them they will be the next generation of leaders. [With these cuts] It’s going to be a challenge to meet our mission.”

It was in this rigid, unforgiving climate that Christina experienced intense fear and isolation. In January, 2015, a clinical social worker at Boston Children’s Hospital wrote to BLS administrators:

[I]t appears that there are significant factors in the school environment which contribute to [Christina]’s anxiety including feeling bullied by teachers and peers. [Christina] did not express any concerns returning to school and again did not appear to be an acute risk to herself or others. Christina is able to return to school as soon as the school is able to accept her.

The note also recommended “that Christina be allowed accommodations for her anxiety. And it requested that any of Christina’s anxiety-related absences should be “distinguished from a lack of desire to attend class, so that appropriate services can be engaged to help her overcome the anxiety.”

Anyone can suffer a panic attack under the right circumstances. Some of the most common symptoms, according to Boston Medical Center, are intense terror, dizziness or feeling faint, fear of going crazy, feelings that nothing is real, sweating, shaking, chest pain or a fast heartbeat, altered reality, or a feeling of being detached from yourself, among other pains and pangs. One way to treat a panic attack is to avoid circumstances that lead to anxiety. According to specialists, Christina’s disappearances from BLS and her inability to present in front of classmates should have suggested to school personnel that she was suffering from panic attacks. Christina also says she was the victim in an abusive relationship with another student and that school administrators were aware of the situation but did not intervene.

Anyone can suffer a panic attack under the right circumstances. Some of the most common symptoms, according to Boston Medical Center, are intense terror, dizziness or feeling faint, fear of going crazy, feelings that nothing is real, sweating, shaking, chest pain or a fast heartbeat, altered reality, or a feeling of being detached from yourself, among other pains and pangs. One way to treat a panic attack is to avoid circumstances that lead to anxiety. According to specialists, Christina’s disappearances from BLS and her inability to present in front of classmates should have suggested to school personnel that she was suffering from panic attacks. Christina also says she was the victim in an abusive relationship with another student and that school administrators were aware of the situation but did not intervene.

A little over a month after Christina was given an individualized learning plan, Assistant Headmaster Flynn emailed the Smiths. Christina had been spotted roaming the halls. For this infraction and alleged others, Flynn wrote, “I will be scheduling a disciplinary hearing for leaving the school building without permission; repeated cutting of classes; repeated failure to report to detention; repeated and flagrant violations.”

Mr. and Mrs. Smith were confused. When a student is found eligible for special education and is put on a program that provides her with certain academic accommodations, the members of her IEP team are supposed to communicate with teachers and staff so as to avoid situations where she is punished or denied accommodations related to her learning disability. The IEP team is also required to have scheduled check-ins with the student to monitor her progress and, if needed, make necessary adjustments to the student’s educational course.

According to their daughter’s IEP, furnished by the school’s own specialists, Christina was allowed to do these things — if her anxiety, for example, which she couldn’t control, left her in fear of attending class, then skipping wasn’t grounds for disciplinary action.

“It’s against the law to punish a child if you can prove [the reason for the punishment] was related to his or her disability,” says Kast-McBride, who served for 11 years as the head of the Boston Special Needs Parent Advisory Council.

THE DEAL

[Christina] has repeatedly left the school building without permission, including on Thursday February 5, Friday, February 6, and Wednesday, February 11, 2015 and on other earlier dates since the start of the school year; she has cut numerous classes; she has failed to report to detention. These behaviors represent repeated and flagrant violations of the Code of Conduct. As a result of these behaviors, [Christina] may be suspended for up to five days and sent to the Counseling and Intervention Center for five days.

So reads an email to the Smiths from Assistant Headmaster Flynn dated two weeks after Boston Children’s determined Christina should be excused for anxiety-related absences. Though Christina’s IEP allowed her to miss class during bouts with anxiety and even to dismiss herself from school, BLS administrators denied her such accommodations in apparent violation of Commonwealth education laws. Among other protections, regulations state: “Once eligibility has been determined, the type of disability of the student shall not be used to provide a basis for labeling or stigmatizing the student. Additionally, the type of disability shall not define the needs of the student and shall in no way limit the services, programs, or inclusion opportunities provided to the student.”

Mr. and Mrs. Smith called the proposed suspension into question, but the punishment was upheld by BLS administrators. When the family appealed the decision, taking the case to the Bureau of Special Education Appeals (BSEA), the state board responsible for resolving and providing mediation for disputes related to special education services and protections granted students receiving special education, Latin School Headmaster Mooney Teta and the school’s legal team made the Smiths an offer they couldn’t refuse.

Christina was unlikely to return to BLS given the circumstances. So on March 20 of last year her parents signed an on-the-spot handwritten agreement: In exchange for their daughter’s record being scrubbed of the stains left from administrators saddling her with bad behavior points for missed classes, the Smiths agreed to move Christina to the John D. O’Bryant School for Mathematics and Science in Roxbury, another one of Boston’s exam schools. For BLS, the handshake meant the whole ordeal would probably remain out of the public eye — no allegations of sexual misconduct, no questions about how BLS handles students with special needs.

EPILOGUE

As soon as Christina was placed on an IEP, she became part of the special education system. Like millions of other young Americans with unique needs, the responsibility to provide Christina with a free and appropriate education was then thrust squarely on her school district. Because districts are allowed to move special ed students if a current placement isn’t providing the necessary support, however, BLS — despite its unrivaled resources among Boston public schools — was not mandated to accommodate Christina. Instead, they soiled a student’s record in order to apparently force her withdrawal.

National statistics suggest Christina’s experience was not out of the ordinary. According to the US Department of Education and the Office for Civil Rights Data Collection services, “students with disabilities are twice as likely to receive an out-of-school suspension as their non-disabled peers.”

Christina dropped out of the O’Bryant after three months. “That school was great,” she says. “I liked that school a lot. I left because I didn’t want to be in high school.” Mr. Smith says the O’Bryant wasn’t able to address his daughter’s needs. Christina now takes classes at Bunker Hill Community College.

With an investigation into BLS practices underway by the US Justice Department and an ongoing campaign by concerned students organizing under the #BlackAtBLS banner, analysis of how Latin School teachers and administrators handled issues around race will be brought to unprecedented light. As minority BLS families publicly speaking out and their allies have stated, their criticisms have been simmering for years and still have not been sufficiently addressed. As for special needs issues: With Christina out of school and her dad spending less time on the BLS parent listserv, it’s up to the less than 2 percent of BLS students who receive special services and their families to speak up now. Or forever hold their IEPs and transfer.

(Additional research and editing by HALEY HAMILTON)